Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Why This Canvas Matters

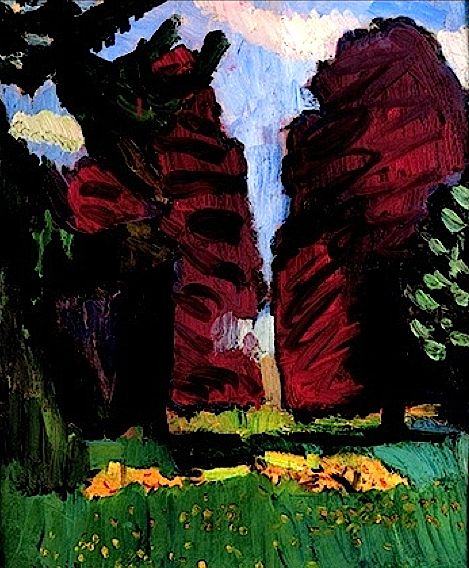

“Copper Beeches” (1901) belongs to the brief but decisive period when Henri Matisse was testing how far he could shift from academic description toward a color-led construction of form. He had already absorbed strict life-drawing discipline in Paris and was studying the structural color of Cézanne, the simplified planes of Gauguin and the Nabis, and the charged brushwork of Van Gogh. In 1901, working in Switzerland and northern France, he used the landscape as a laboratory: stable motifs, direct light, and room to experiment. “Copper Beeches” is one of the clearest statements from that year, compressing a grove into a handful of bold vertical masses and a saturated chord of red, green, yellow, and blue. You can feel the imminence of Fauvism—color chosen for its power to build and balance, not for docile imitation—while the picture still retains the scale, weight, and quiet of a plein-air study.

First Look: A Grove Reduced To Forces

At first glance the painting reads like a heraldic emblem. Two towering, wine-red beeches flank a narrow interval of sky and distant trees. A darker tree or shadowing trunk anchors the left edge; a cooler evergreen silhouette bites into the right, its foliage articulated by small, oval strokes. The foreground is a green lawn strewn with yellow leaf-litter or flowers, cut by a dark horizontal that may be a low shadow or path. The sky appears in slivers—thin bands of pale blue and cloud white peeking between the crowns. There are no figures, no paths to wander down, almost no middle distance. The subject has been pared to an encounter: stand here, look up, feel the weight of these beeches. That concentration is the modern note.

Composition: A Triptych Of Vertical Masses

Matisse organizes the rectangle around a stern geometry. Three major verticals—left trunk, central void of sky, right beech—divide the field like a triptych. The central gap is not empty; it is a bright, breathing strip that throws the red foliage forward. A broad green apron forms the base, a simple plane tilted slightly toward the viewer and punctuated by yellow accents that operate as visual footholds. The horizon is scarcely articulated, forcing the trees to function as architecture. This frontal, close-range framing denies picturesque recession and asks you to experience the grove as a wall of color and air. The effect is monumental despite the painting’s intimate scale.

Color Architecture: Red Against Green, Light Against Weight

The picture’s structure is chromatic. Copper beeches earned their name from the deep red-violet of their leaves; Matisse exaggerates that chroma until the canopies become dense clots of alizarin-like crimson warmed with earth browns and cooled by violets. Against them he lays an elastic field of greens in the grass—sap-green passages enriched with viridian and yellow notes—and a cooler blue-green in the right-hand evergreen. Yellow operates as a catalyst, ringing the base of the trees and scattering across the lawn to ignite the green. Black or near-black strokes in the trunks and the central seam compress energy rather than extinguish it. The sky is spared to a few slips of pale blue and white, enough to register atmosphere without diluting the chord. Everything is relational: the reds flare because the greens are clean; the greens glow because the reds are deep; the yellows sharpen both.

Brushwork: Direction, Speed, And Materiality

The surface is a ledger of decisions. In the foliage, Matisse drags dark, diagonal strokes across the red masses, a shorthand for the directional lay of leaves and a way to aerate large fields without dissolving their weight. In the evergreens at right he uses compact, comma-like dabs to articulate clustered needles, letting the darker ground show through as shadow. The lawn is handled in broader, lateral pulls interspersed with compact yellow touches that break the plane into lighted zones. The sky is laid thinly, with soft, horizontal strokes that read as cloud and that give the eye a resting plane. The brush communicates tempo: slow pressure for trunks, quick slashes for leafage, measured glides for grass. That variety assigns a physical “speed” to each material and keeps the whole surface animated.

Light And Weather Without Theatrical Shadow

Natural light organizes the scene but never dictates it. There is no single, dramatic sunbeam casting hard shadows. Illumination is a high, steady daylight that clarifies edges and saturates color. The beeches deepen toward their lower halves, where light is occluded; the lawn sparkles with yellow where sun hits the cropped grass; the sky glints between crowns. Instead of chiseling with shadow, Matisse models by temperature: cooler notes carve recesses in the red canopies; warmer strokes swell the sun-facing planes of the lawn. The light feels breathable—present everywhere, tyrannical nowhere.

Space Compressed Into A Decorative Field

Depth exists only as much as required. The dark band behind the yellow leaves hints at a receding plane; the sliver of pale blue suggests sky distance; the evergreen’s overlap establishes near-far relation. Yet recession is deliberately shallow. The trees push forward like screens; the lawn tips up; the whole image reads as an upright tapestry. This compression is not a failure of perspective; it is Matisse’s choice to keep the painting’s first allegiance to the flat surface. He composes a balanced fabric and then lets the eye discover space within it, not the other way around.

Drawing By Abutment, Not Outline

There are few hard contours in “Copper Beeches.” Edges emerge where color fields meet. The left trunk is “drawn” by the join of near-black and green; the red canopies are shaped against the slips of sky; the evergreen is clipped out by putting oval green marks over a darker ground. Where a line appears—at the base of a trunk, in a quick hook along a branch—it is broken and absorbed into neighboring strokes. This method preserves the unity of the surface and allows color to carry both modeling and boundary.

The Motif As Motive: Why Beeches?

Copper beeches are decisive trees: compact masses, commanding presence, unusual hue. For a painter turning away from tonal modeling, they offer a ready-made experiment. Their color pushes against a green environment, their bulk tests compositional balance, their leaf texture begs for rhythmic strokes. By choosing beeches, Matisse can work almost abstractly—two red masses, one green mass, a sash of sky—while remaining fully faithful to a real place. The motif licenses the method.

The Lawn: A Stage Of Accents

The foreground is more than a base; it is a stage. Matisse distributes yellow notes like dropped petals or sun-struck leaves that set up a counter-rhythm to the heavy verticals. Those accents also scale the scene: small enough to read as ground detail, bright enough to keep the eye from sticking to the upper mass. The dark horizontal that runs behind them acts as a threshold line, separating viewer space from tree space. Stand here, the painting says; the grove begins there. With a few notes and one seam, Matisse constructs a platform for the drama above.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path

The composition encourages a looped route. The eye often enters through the bright yellows in the grass, climbs the left trunk, traverses the red canopy in zigzag slashes, drops through the sky slit, mounts the right canopy, and finally descends the evergreen’s dotted edge back to the lawn. Each circuit clarifies another relation—the dialogue between thick red and thin blue, the way small green ovals modulate the right edge, the role of the dark band in anchoring the yellow. The painting does not ask to be decoded; it asks to be walked, visually, like a short path through a stand of trees.

Emotion And Season Encoded In Palette

Everything about the palette suggests late summer or early autumn. The greens are still lively but warm; the yellows read as leaves gathering on grass; the red beeches are at full power. The mood is not nostalgic or elegiac; it is concentrated and alert. The high contrast between red and green generates energy, while the short sky passages bring a cool, clearing calm. Many landscapes whisper; this one speaks plainly: stand with the trunks, feel their weight, breathe the sharp air.

Dialogues With Predecessors And Peers

“Copper Beeches” converses with Cézanne in its construction of mass by abutting planes and directional strokes. It shares with Gauguin and the Nabis a decorative simplification of shapes and a willingness to let non-local color do structural work. Van Gogh’s influence is audible in the rhythmic notations of leaf and trunk. Yet the temperament is Matisse’s—more balanced than Van Gogh, less hieratic than Gauguin, calmer in its courage than the Nabis. The aim is not agitation or symbol but a stable, legible harmony powered by saturated color.

Materiality: Pigments, Layering, And The Breath Of The Ground

The beeches’ reds likely combine deep alizarin crimson or madder lakes with earths; the greens mix viridian/sap with yellow; the blues are cobalt or ultramarine moderated with white. Matisse varies thickness: lean, semi-transparent passes in sky and some grass let the underlayer shine; fuller paint in the red masses catches actual light and increases their physical weight. In several places the weave of the fabric registers, especially in lighter areas, adding a grain that keeps wide fields from going inert. The painting’s material truth—oil dragged, dabbed, and scumbled—remains visible and is part of the work’s meaning.

Abbreviation And The Courage To Leave Things Out

There is no bark texture, no leaf vein, no catalog of twigs. Distant architecture, if any, is suppressed. Matisse’s omissions are strategic; they keep the motif legible at the scale of a glance and prevent detail from weakening the color chord. The viewer supplies the rest. That collaboration between painter and eye is one of modernism’s most durable pleasures and one of the reasons the picture still looks fresh.

How To Look Slowly

Begin by letting the main chord register: red masses, green base, dark trunk, blue slips, yellow sparks. Then study edge behavior—where the red meets the sky, where the evergreen’s ovals sit over darkness, where the grass plane breaks on the dark seam. Next, attend to stroke direction; let your eye feel the swing of each diagonal in the canopies. Finally, step back until the painter’s edits disappear and the grove becomes a single, convincing presence. That near-far oscillation mirrors the way Matisse built the picture: test a relation, step back, adjust, repeat.

Relationship To Matisse’s 1901 Landscapes

Set “Copper Beeches” beside “Swiss Landscape” or “The Bridge” from the same year and a shared grammar appears: frontal planes, high-key complements, color unity before linear detail, and a shallow, designed space. What distinguishes “Copper Beeches” is the audacity of its simplification. Where the Swiss scenes offer roads, houses, and skies to pace the gaze, this canvas gives you almost nothing but trees and grass. It is a stricter exercise, and that strictness clarifies the stakes: can a handful of tuned hues and decisive strokes hold a world together? The answer is yes.

The Decorative Ideal Emerging From Observation

Even in this outdoor subject, Matisse is moving toward the decorative ideal he would later describe—an art of balance, clarity, and restful unity. Each zone has a role: red crowns supply weight; green base offers lift and cool; yellow accents quicken; blue slips ventilate; dark seams anchor. The grove is observed, but it is also composed like a wall hanging, a fabric of interlocking shapes whose relationships are the true subject. The painting articulates a way of seeing that will power his interiors and figure groups for decades.

Why This Painting Endures

“Copper Beeches” endures because it translates a common motif into a compact demonstration of modern pictorial thinking. It shows how color can shoulder the tasks once assigned to line and shadow; how omission, rather than impoverishing a scene, can purge it of noise; how an outdoor subject can be both faithful and decorative. The grove is not merely shown; it is built from forces—vertical thrust, chromatic opposition, rhythmic stroke—that the viewer feels instinctively. The result is an image that is simple to grasp, rich to revisit, and unmistakably Matisse.