Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

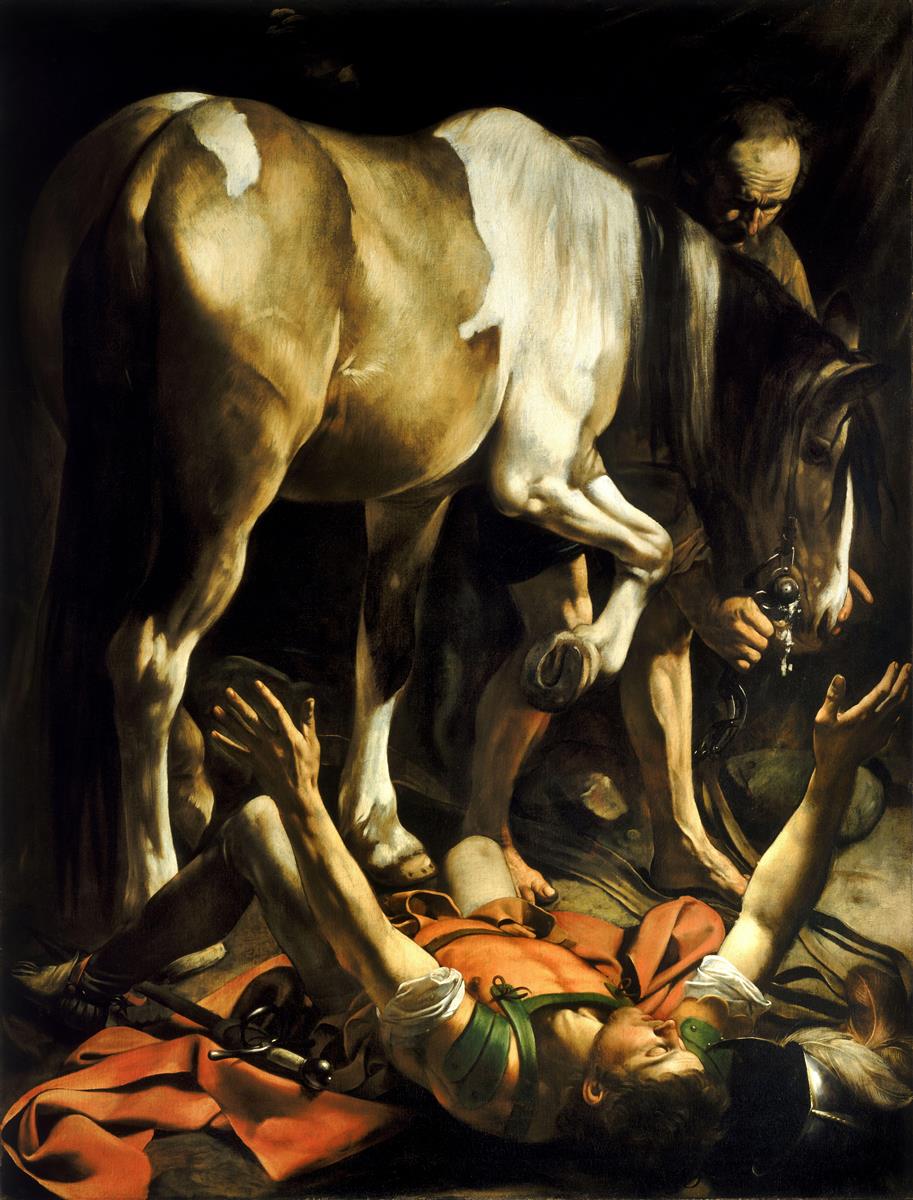

Caravaggio’s “Conversion on the Way to Damascus,” painted in 1601 for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, compresses the thunder of revelation into the quietest, strangest arrangement: a fallen man, a patient horse, and an elderly groom inside a pocket of darkness. Saul lies on his back in a blaze of light, arms flung open as if receiving an unseen embrace. The horse—monumental, flank to the viewer—fills most of the canvas, one hoof lifted delicately above the convert. The groom leans forward to steady the bridle, his attention absorbed by the animal rather than the miracle. No sky splits, no angels descend. The voice that changes history is not pictured. Instead, Caravaggio shows what a voice does to bodies. The scene feels at once intensely private and universally legible: the instant a will surrenders and a new life begins.

Historical Context

The Cerasi Chapel commission paired this canvas with the “Crucifixion of Saint Peter.” Together the two works present a diptych of beginnings: the instant Paul becomes an apostle and the moment Peter seals his confession in martyrdom. Rome at the turn of the century wanted art that was clear to ordinary eyes and alive with moral consequence. Caravaggio had just electrified the city with the Contarelli Chapel cycle, where he staged sacred episodes in contemporary interiors lit by purposeful beams. For the Cerasi Chapel he carried the project further by subtracting nearly everything that looked like theatrical scenery. The conversion is not a pageant; it is an event that could occur behind a stable door. The boldness of this minimalism—horse flank dominating a biblical scene—marked a decisive turn in Baroque storytelling.

Subject and Narrative Instant

Acts 9 recounts that Saul, persecutor of Christians, was struck by a heavenly light and heard a voice ask, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” Blinded, he was led into Damascus, where his sight was restored and his mission changed. Caravaggio chooses the second after the fall. Saul’s sword lies inert. His helmet has rolled aside. His body is intact but transformed, every muscle of resistance drained by the impact of meaning. Unlike earlier versions—his own crowded 1600 “Conversion of Saint Paul”—this work shows no scrambling soldiers, no rearing cavalry. The world has narrowed to the convert, the animal that nearly crushed him, and the man who tends the bridle. The story becomes a meditation on attention: God addresses one person; the rest of the world continues with its necessary work.

Composition and the Architecture of Surrender

The painting’s geometry is a revelation of its own. The horse’s body forms a great curving mass that occupies the upper two-thirds of the canvas, its haunches and barrel modeled like cylindrical columns. The lifted foreleg creates a poised arch above Saul’s torso, simultaneously threatening and tender. Saul lies along a diagonal that runs from the lower left to the upper right, his arms forming a wide V that arrests the eye. The groom’s bent figure counters this diagonal with a compact triangle to the right, stabilizing the composition. The three bodies together compose an image of shelter: the horse’s bulk as roof, the groom as pillar, and Saul as altar. The space is shallow and intimate; the picture presses forward to the viewer like a confession.

Chiaroscuro and the Behavior of Light

Light enters from the upper left and pours downward in a cataract that stops exactly where it must—on the convert’s face and open hands, on the horse’s muscled flank, and on the groom’s forearms. Everything above and behind recedes into tenebrae. Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro functions like narration. The beam reads as the voice that is not painted; it explains what the figures feel. It is neither generalized daylight nor special effect; it is moral architecture. The light grants visibility to the world as it aligns around a new center: Saul’s consent. Shadows pool under the horse and around the groom’s legs, amplifying the sense that the conversion happens in a privacy inside the world, a sanctum created by darkness and focus.

The Horse as Monument and Witness

Caravaggio’s horse is no anecdotal prop. It is the painting’s largest presence and, paradoxically, its quietest. The animal’s coat glows with creamy whites and tawny browns, its tail hanging in a gentle arc, its lifted hoof frozen in a courteous hover above the fallen man. This near-miss—hoof suspended, not striking—turns brute mass into sheltering weight. The horse’s turned head and lowered ears suggest calm curiosity rather than panic. In making the animal central and dignified, Caravaggio offers a theology of creation alongside conversion: nature does not rage against grace; it makes room for it. The horse, schooled by the unseen voice and the groom’s steady hand, becomes a living architecture that protects the moment.

The Groom and the Ethics of Ordinary Work

The groom, absorbed in the bridle and oblivious to the revelation, embodies the world’s continuity. He keeps the animal from stepping on the prone man, practicing the modest craft that saves lives without fanfare. His gaze never lifts. Caravaggio grants him the dignity of concentration: veins rise on the forearms; knuckles whiten around the bit; knees brace with habitual knowledge of weight. The groom’s presence insists that conversion does not abolish ordinary work; it requires it. Someone must hold the reins when light falls.

Saul’s Body and the Language of Consent

Saul’s pose departs from the melodrama of flailing limbs seen in many conversion scenes. His eyes are closed; his mouth relaxes; his arms open wide in a gesture that fuses surrender and reception. One leg bends under him, the other extends into shadow; the red cloak pools like a warm halo beneath his back. Caravaggio paints the armor with affectionate realism—the green leather strap crossing the chest, the polished curve of the gorget—but strips it of power. The sword, once a line of decision, is now a still diagonal that points nowhere. Surrender here is not collapse; it is a learned stillness. The body becomes an instrument tuned to a new address.

Silence, Sound, and the Invisible Voice

Because paintings are silent, artists often overcompensate with spectacle. Caravaggio does the opposite. The quiet is so dense the viewer hears it: the slow breath of a horse, the soft clink of metal tack, the rasp of a cloak against dirt. Against this soft soundscape the unpainted voice becomes more credible. We infer it by consequence—by the way Saul’s arms open, by the way the horse pauses, by the way the groom leans. The conversion arrives as a pressure that rearranges attention and posture rather than as a pictured apparition. Caravaggio thus crafts a visual theology of hearing: a word can be seen in the bodies it changes.

Space, Scale, and the Intimacy of the Stable

The setting is ambiguous: an enclosure or road-edge so tight it functions like a stable. The lack of horizon denies escape. Caravaggio couples that confinement with oversized scale—the horse monumental, the men nearly life-size—so that the viewer stands in the same pen. We feel the warmth of the animal, the coarseness of the ground, the shadow pushing in from every edge. Such intimacy converts viewers into witnesses rather than spectators. We are not looking at history; we are inside it, close enough to reach for the bridle or to whisper assent with the convert.

Iconography Reduced to Essentials

Early Renaissance versions often depict a blazing Christ in the sky, city walls in distance, and soldiers tumbling from horses. Caravaggio reduces the iconography to three elements: the body that surrenders, the creature that almost crushed him, and the worker who holds the world steady. A fallen helmet and idle sword hint at Saul’s previous confidence. The red cloak signals ardor that will be redirected. Otherwise there is only light. This reduction is not poverty but concentration. The painting tells us that conversion is not a pageant of extras; it is a transaction between a person and grace, witnessed by creatures and neighbors who keep their tasks.

The Theology of the Open Hands

The open hands are the painting’s clearest doctrinal statement. They are not clasped in prayer or thrown up in fear; they are receptive. The gesture implies that faith begins as being addressed, continues as listening, and arrives at consent. Caravaggio’s choice to make both palms visible locks the meaning into the body’s grammar. One palm faces the horse—a pledge of harmlessness; the other faces the unseen light—a willingness to receive. The hands preach without words, and the viewer understands instinctively: this is what saying yes looks like.

Color and the Emotional Climate

The palette is disciplined. Warm ochres and creams sculpt the horse; olive and green glint across leather armor; a radiant fold of orange-red cloak keeps the scene from draining into sobriety. The cloak’s color warms the earth tones, marking Saul with the emotional charge of zeal even in surrender. Caravaggio’s blacks and browns are not empty; they are saturated air, the kind of darkness that lets light be authoritative rather than decorative. The total climate is hushed, warm, and breathable, a space where insight can land and expand.

Technique and Paint Handling

Caravaggio builds forms with large tonal masses, then cuts edges sharply where light breaks on volume. The horse’s hide is laid in with buttery passages of paint, the highlights dragged wet over wet to imitate sheen on hair and muscle. Flesh is handled more thinly, allowing warm underlayers to bloom through cooler hits at wrist, forearm, cheek, and knee. Metal is crisp and economical—the helmet’s rim, the strap’s buckle, the bridle’s bit—never fussy, always legible. The ground is a matrix of darks scumbled with lighter passages, convincing as dirt without distracting from the bodies. The painter’s economy is severe; every stroke earns its place.

Comparison with the Earlier “Conversion of Saint Paul”

The crowded 1600 version shows the social blast radius of revelation—panicked horsemen, an angel leaning toward Saul, light thundered into turmoil. This later canvas shows the inward settling: the world has quieted, and only the necessary remains. Read together, the pair offers a phenomenology of change. First there is shock—the body thrown, companions shouting, a voice like a blow. Then there is acceptance—the body open, the animal calmed, work resumed around a new center. By choosing the second register for the chapel, Caravaggio aligns Paul’s beginning with Peter’s end across the nave: both scenes display radical trust enacted through bodies rather than through spectacular visions.

The Viewer’s Role

Standing before the painting, one feels invited into the triangle of grace, creatureliness, and labor. The viewer can almost take the groom’s place, steadying the bridle while the convert breathes. Or one can lie where Saul lies and imagine the weight leaving the chest as resistance dissolves. Caravaggio’s staging fosters such imaginative participation by removing narrative clutter; with fewer actors, each of us becomes the missing one. The work thus functions devotionally without didactic text: it teaches by letting us stand where assent happens.

How to Look

Let the eye begin at the lifted hoof and ride the curve of the horse’s belly to the glowing patch of shoulder. Drop along the bridle to the groom’s hands and feel their competent pressure. Fall from there to Saul’s open palms and rest on the luminous triangle formed by his forearms and crimson cloak. Slide to the abandoned sword and helmet, then back to the gentle arc of the horse’s tail. Repeat this circuit until the rhythm becomes familiar: weight, care, consent. The painting’s meaning lives in that rhythm.

Reception and Influence

Contemporaries were astonished that a horse could dominate a sacred narrative. Some complained; others recognized the breakthrough. Artists across Europe learned from the canvas’s radical economy and its refusal of ornamental miracle. Later painters adopted the strategy of letting a single, ordinary thing—an animal, a tool, a shaft of light—carry metaphysical weight. The image also entered spiritual imagination, shaping how generations pictured conversion: not an escape from the world but a reorientation within it, surrounded by creatures and neighbors doing their work.

Conclusion

“Conversion on the Way to Damascus” is Caravaggio’s most distilled account of how a life turns. A man falls; a horse pauses; a worker steadies a bridle; light chooses, touches, and clarifies. Without inscriptions or sky-borne apparitions, the painting renders revelation visible through posture and attention. It proposes that the sacred arrives not by overwhelming the everyday but by inhabiting it so fully that the everyday rearranges itself around a new center. Saul’s open hands are the hinge. In that gesture the persecutor becomes a listener, the listener becomes a witness, and the road becomes a chapel. The horse waits; the groom holds; the world is ready for the next step.