Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to Georges Valmier and His Abstract Vision

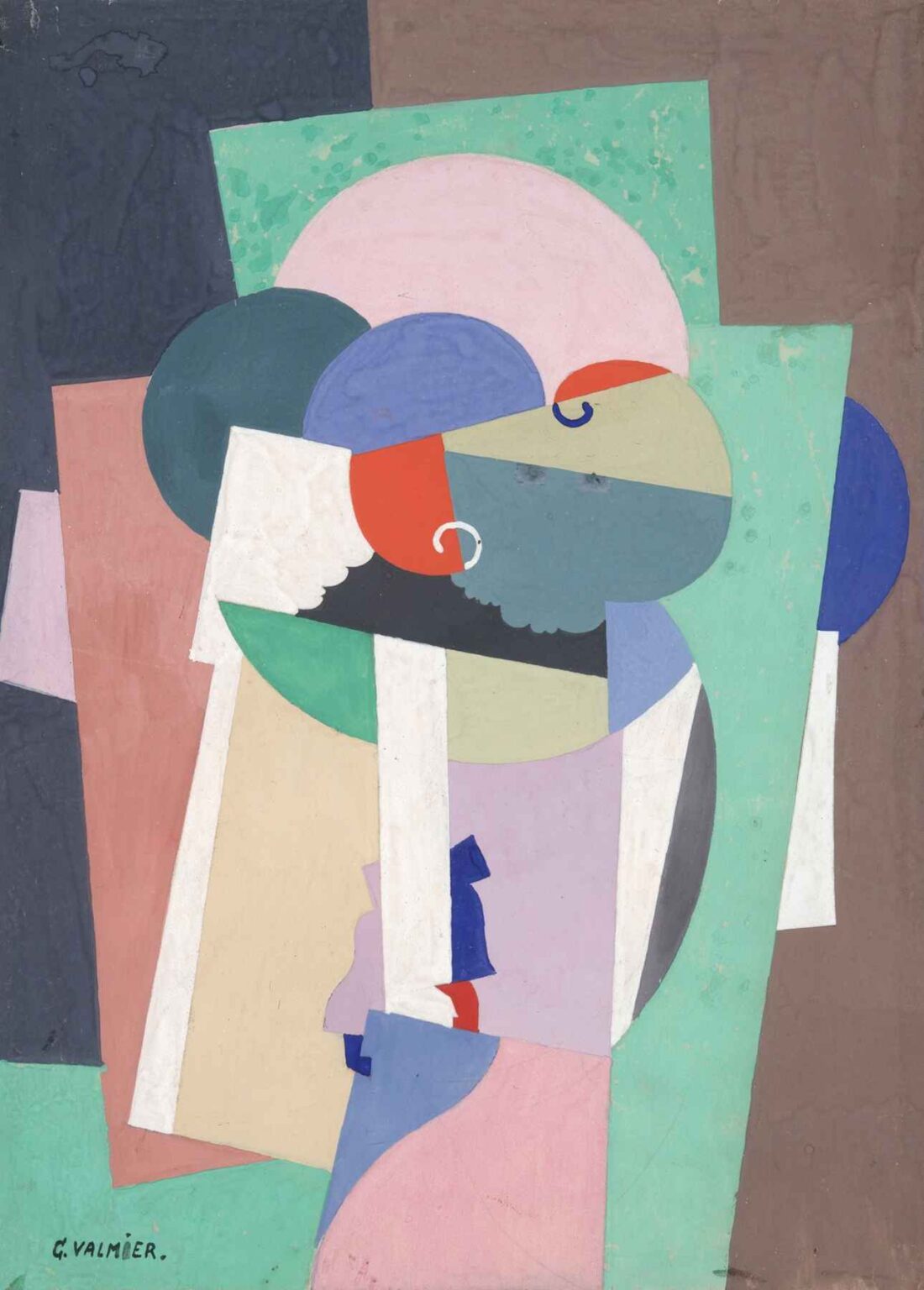

Georges Valmier, a pivotal figure in the development of modern abstract art in early 20th-century France, is known for his seamless transition from Cubism to pure abstraction. His painting “Composition (No. 7888)” exemplifies his mature style: bold, architectural, and symphonic in its interplay of shape and color. Though lesser known than his contemporaries Picasso and Léger, Valmier’s work is equally important for understanding the evolution of geometric abstraction in European modernism.

The Context of the Work

“Composition (No. 7888)” was created during a time of radical experimentation in visual language. The painting likely dates from the 1920s, a period when Valmier had embraced non-objective painting after earlier flirtations with Cubist and Fauvist styles. Artists were breaking with representation and leaning into the emotional and spiritual power of color and form alone.

Valmier’s background in music, as well as his theatrical design work, had a significant influence on the way he approached painting. His compositions are often likened to musical arrangements—each form and color playing the role of a note or rhythm in a greater orchestral movement. This musicality permeates Composition (No. 7888).

Structural Arrangement and Design

The most immediately striking aspect of Composition (No. 7888) is its compositional harmony. The canvas is filled with an intricate layering of geometric shapes—rectangles, circles, ovals, and planes—stacked and overlapped with apparent spontaneity, yet finely controlled precision. Each element seems to interlock with the others, creating a rhythmic movement across the surface.

Vertical white bars serve as structural columns, anchoring the eye and providing a sense of stability amid the swirling interaction of colored forms. Triangles, semicircles, and curved edges soften the rigidity of the straight lines, balancing dynamism with calm. The arrangement invites repeated viewing, as each glance yields new relationships and hidden details among the elements.

Color Palette and Its Emotional Resonance

Valmier’s palette in this composition is both subdued and vibrant. Soft pastels—mauve, sage green, dusty pink—converse with saturated accents like crimson, deep blue, and bright white. These colors do not scream; they hum gently, evoking a contemplative, introspective mood. The painting’s background is rendered in earthen brown and black, enhancing the saturation of the foreground elements.

There’s a deliberate modulation in tone throughout the work. No one color dominates. Instead, Valmier guides the viewer’s eye with visual contrast and color echo—an arc of red here, a mirrored patch of pale blue there. The gentle collisions of color feel musical, reinforcing the idea that this painting is as much a visual score as it is an image.

Visual Rhythm and Spatial Illusion

Although flat in execution, Composition (No. 7888) creates a sense of depth and layering that challenges traditional spatial expectations. Valmier accomplishes this through overlapping shapes and varied tonal values. The placement of darker forms against lighter ones creates push-and-pull tension, subtly animating the surface of the painting.

There is no discernible vanishing point or realistic space, yet the work breathes and shifts like a living structure. The viewer is invited to navigate the work vertically and diagonally, not linearly. The balance between chaos and control evokes a quiet internal logic—one that mirrors the rhythms of the natural world without imitating it directly.

Influence of Cubism and the Move Beyond

Valmier began his career deeply influenced by Cubism, and this early training is evident in the compositional structure of Composition (No. 7888). However, by this stage in his artistic evolution, he had shed the Cubist reliance on object deconstruction. What remains is Cubism’s geometric rigor and spatial fragmentation, transformed into something more poetic and abstract.

In many ways, this painting represents a bridge between Cubism and later abstractionists like Sonia Delaunay, Piet Mondrian, and even the Bauhaus artists. Valmier’s forms are more rounded, his palette more lyrical, his vision more synthetic than analytic. This work isn’t dissecting the world—it’s inventing a new one.

Symbolism and Non-Representation

One of the most compelling aspects of this painting is its lack of direct symbolism. There are no clear allusions to people, places, or objects. Yet this absence does not render the work cold or clinical. On the contrary, Valmier imbues the painting with emotional texture and intellectual curiosity by eliminating narrative content.

The forms and colors become signifiers of inner states—balance, tension, unity, and dissonance. The red and white arcs, for example, might suggest dualities: motion and pause, heat and light. The circular shapes conjure the idea of completeness, while intersecting angles evoke disruption or innovation. In this sense, the painting becomes a kind of visual meditation on harmony and fragmentation.

The Impact of Theater and Set Design

Valmier’s experience designing theatrical sets clearly influenced the spatial logic of his abstract paintings. In Composition (No. 7888), the forms function almost like stage flats—standing upright, layered, and coexisting in an illusionistic space. There’s a sense that the shapes could move, rotate, or collapse, like props in a surreal ballet.

This theatricality also helps explain the vivid contrast and deliberate positioning of elements. Valmier was not merely arranging for balance; he was choreographing a visual experience meant to evoke atmosphere, much like a stage scene lit with colored lights and shadow. Every piece of the composition plays its role.

Emotional Underpinnings and Atmosphere

While wholly non-objective, the painting radiates a certain human warmth. The earthy undertones in the color palette, the curvilinear softness of many shapes, and the nested layering create a sense of intimacy. There’s no aggression or irony here—only quiet confidence and intellectual rigor.

This emotional register separates Valmier from other abstractionists of his time. Where Mondrian embraced the universal and spiritual, Valmier embraced the personal and sensory. The painting does not ask to be deciphered like a puzzle; instead, it opens itself to mood and movement, echoing feelings rather than facts.

The Role of Texture and Surface

Unlike heavily impastoed modernists or the polished perfection of some Bauhaus works, Valmier’s surface remains relatively matte and flat, focusing attention on the geometry rather than the brushwork. That said, subtle texture plays a role. The layering of pigment gives weight to the composition. Slight inconsistencies in color application suggest hand craftsmanship, reminding the viewer that this precision is still deeply human.

These painterly details soften the mechanical impression that might otherwise arise from so many crisp, defined shapes. The result is a work that feels tactile and genuine, even while it engages with ideas of order and abstraction.

Valmier’s Contribution to Abstract Modernism

Valmier remains an underrecognized but significant voice in the story of abstraction. His commitment to lyrical form, his deep understanding of color theory, and his ability to fuse visual art with music and design make him a pivotal figure in the transition from representational modernism to fully abstract painting.

Composition (No. 7888) encapsulates this legacy. It is a painting that celebrates the capacity of abstract art to evoke feeling, structure, and harmony without relying on visual storytelling. Its intelligence is matched by its elegance.

Final Reflections

In Composition (No. 7888), Georges Valmier achieves a remarkable synthesis of geometry and grace. Through layered forms, refined color harmonies, and quiet emotional depth, the painting offers an enduring meditation on abstraction itself. It’s not a painting that demands to be solved—it simply asks to be seen, heard, and felt.

Valmier invites us into a visual symphony—one in which shape and shade are the instruments, and the resulting music is as timeless as it is modern.