Image source: wikiart.org

The Summer When Interiors Learned to Breathe

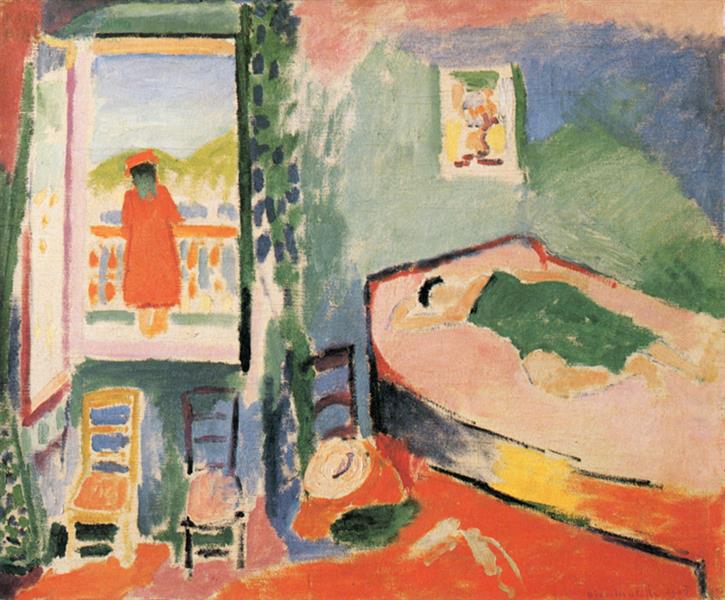

Henri Matisse painted “Collioure Interior” in 1905, during the blazing Mediterranean summer that gave birth to Fauvism. Working side by side with André Derain in the fishing town of Collioure, Matisse discovered that color could be architecture, light, and emotion all at once. This small canvas captures that breakthrough inside four walls. It is a domestic room animated by saturated hues, tilted planes, and open air pouring through a balcony. Rather than describing furniture and figures with careful shading, Matisse lets hot reds, cool greens, and milky blues construct the space; he uses a few black accents as a brace; and he allows reserved patches of primed canvas to shine as real light. The painting reads as an intimate scene and, at the same time, a manifesto about what modern painting can do.

Subject and First Impressions

The composition divides into two zones: at left, a tall open door frames a figure in a red dress leaning on a balcony; at right, a curved bed holds a reclining body covered by a green cloth. Chairs, a hat, and scattered objects mark the lower half. A patterned green curtain hangs like a vertical plume between inside and out. Walls are blocks of turquoise, celadon, and violet; the floor is a field of orange-red that seems to warm the entire room. The impression is immediate and legible even before the eye names things. Color gives you the temperature of the day and the mood of the inhabitants; the drawing merely keeps the elements from drifting apart.

Composition Built from Oppositions and Echoes

Matisse organizes the room as a conversation between inside and outside, vertical and horizontal, rest and watchfulness. The open doorway is a cool vertical rectangle, a window of blue air; the bed is a warm tilted ellipse, a mass that anchors the right half. The green curtain falls like a hinge between the two, binding the halves and preventing the composition from splitting in two. Three chairs form a stepped rhythm from foreground to background, their ladder-back slats echoing the balcony rails outside. The path of the eye runs in a loop: enter at the red floor and hat, rise through the chairs to the balcony figure, cross the curtain to the pale wall, slide to the large curved bed, and return along the yellow flare at the bed’s edge. The room’s geometry is clear without a single academic construction line.

Color as the Architecture of the Room

The painting proves that color can carry structure. Warmth advances; coolness recedes. The wide carpet of cadmium red pulls the foreground toward us. Turquoise and mint walls slip back, opening air in the center of the picture. The bed’s coverlet is a saturated grass green with darker seams that state folds more convincingly than brown shadow could. The figure at the balcony blazes in vermilion against a pale outdoor light so that the doorway behaves like a lantern. Matisse relies on complementary pairs—red against green, yellow against violet, blue against orange—to energize each boundary. The effect is not merely decorative. It is functional, because those temperature jumps define edges and give the room depth while keeping the surface bright.

Light and Mediterranean Atmosphere

No direct sunbeam is painted, yet the room feels flooded with day. Matisse achieves that glare by thinning his paint in many passages so the primed canvas peeks through, especially in the sky, the floor’s highlights, and the pale wall near the bed. Those reserves are literal light, not simulated reflections. The balcony’s pale rail and the distant hillside are simplified almost to bands, which sets the clock to midday or early afternoon when forms flatten under strong light. Inside, warm reflections collect along the floor and the bed’s base, a translation of how Mediterranean interiors hold color and heat.

Brushwork, Impasto, and Material Decisions

The touch is frank and varied. In the green curtain, quick, comma-like strokes pattern the fabric without drawing every leaf; on the bed’s coverlet, heavier, curved sweeps imply weight and nap; in the sky and walls, paint is scrubbed thinly so the weave of the canvas participates as brightness. Matisse does not polish away evidence of the hand; he wants the mark to remain visible because the mark is the unit of sensation. Where he needs structure, he hardens his edges with black or purple; where he needs breath, he lets color feather into the ground.

Space Without Linear Perspective

Depth is created by overlap, scale, and temperature rather than by converging orthogonals. The chairs diminish in height as they retreat, the bed overlaps the floor, the curtain overlaps the doorway, and cool hues recede behind warm ones. The floor tilts toward us in the modern manner, a device that allows the viewer to inhabit the room rather than gaze at it from a fixed station point. The effect is intimate and theatrical simultaneously: a shallow stage on which color performs.

Interior and Exterior as Emotional Poles

The two figures stage a quiet drama of attention. The red-clad person at the balcony looks outward to sea and hills; the reclining figure turns inward to rest. One zone is open, cooled by blue air; the other is closed, warmed by red and yellow. The painting refuses psychological literalism and instead assigns mood to temperature. Outwardness is cool. Inwardness is warm. Between them hangs the green curtain, a living membrane that can swing either way. The room becomes a picture of choice: to step into light or to sink into rest.

The Role of Black and Contour

Matisse’s black lines are sparing and powerful. A dark brace underlines the bed’s front edge; slim black uprights frame the doorway; the chairs carry black accents that steady their positions. These darks are not shadows but structural armatures. They work like lead between panes of stained glass, clarifying the brilliant palette by contrast. Fauvist color needs ballast; here, a few strokes of black are enough to keep the room from dissolving into haze.

Pattern, Decoration, and the Everyday

The dotted curtain, the ladder-back chairs, the small framed picture over the bed, the straw hat on the floor—these repeated motifs reveal Matisse’s belief that domestic things can bear the weight of modern art. Pattern is not an overlay but a way of building space. The curtain’s motif sets a vertical beat; the chair slats introduce a horizontal counter-beat; the bed’s curved edge adds legato. The result is a harmonized interior in which décor and structure are the same language.

A Dialogue with Related Works

“Collioure Interior” speaks to other canvases from 1905. “The Open Window” externalizes the same idea, bathing an interior in saturated outdoor color, while this painting stakes out the boundary between in and out more explicitly. The warm, tilting plane of the floor anticipates “Harmony in Red (The Red Room)” of 1908, where color becomes architecture in total. The relaxed, sun-filled room prefigures the Nice period interiors of the 1920s, when windows, patterned curtains, and recumbent models become constants. In each case, the lesson is the same: color relations can build rooms as reliably as brick and mortar.

Drawing with Edges of Color

Look closely at the bed and you will find no laborious cross-hatching, only a band of yellow against red, a fillet of violet against green. Those seams do the drawing. The balcony figure is stated by a red mass that knocks against pale blue and green; a small black stroke marks the head and neck, and the mind supplies the rest. Even the hat on the floor is simply a ring of ochre and cream edged with purple. This method frees the painting from description while keeping it readable. It is drawing at the speed of light.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Walk

The painting composes a route for the viewer. Begin at the straw hat, leap to the nearest chair, step to the next, and arrive on the balcony with the red figure. Cross the green curtain and drift along the pale wall toward the small framed picture. Drop to the bed’s curve and follow its yellow lip back toward the floor. The path is circular, always returning to the warm center. That circulation is the room’s pulse, and the viewer shares it.

Material Truths and the Sense of Place

The physical behavior of the paint deepens the Mediterranean setting. Thick red-orange on the floor catches gallery light like sun on terracotta. Scumbled blues and whites in the sky simulate glare better than any blended glaze. A slip of raw canvas near the bed stands in for chalky plaster. The painting insists that matter matters: oil paint, when handled frankly, can evoke a climate as sharply as any description.

Why the Picture Still Feels Modern

“Collioure Interior” remains fresh because it relocates accuracy from detail to effect. The balcony rails are not individually drawn, yet the eye trusts them. The bed is hardly modeled, yet it holds a body. The room breathes because color temperatures are right, not because every surface is finished. In a century saturated with images, the painting demonstrates the power of simplification. It shows that by keeping only what carries sensation—warmth, coolness, and transitions between them—an artist can tell more truth than a camera-like record.

How to Look So the Painting Opens

Stand close and pay attention to the edges where colors meet. The yellow slash along the bed’s base is a sunlit edge that melts into the red floor, turning paint into glow. Step back and feel the tug between the cool door and the warm bed. Notice how the green curtain softens that contrast and how the three chairs ladder your gaze toward the balcony. Finally, rest on the small framed image above the bed, a painting within the painting that acknowledges the room as a space for looking. After a few circuits the scene no longer reads as mere furniture and figures; it becomes a map of how color organizes life.

Conclusion: A Room Rebuilt by Color

“Collioure Interior” converts a simple bedroom into a lesson about modern vision. Warm floor, cool doorway, green curtain, curved bed, two figures poised between outward glance and inward rest—these few elements, placed with conviction, generate a complete experience of space and mood. Matisse proves that color can structure a room, carry light, and express feeling without recourse to heavy modeling or detailed contour. The painting is both an affectionate record of a summer room and a milestone on the road to the great interiors that would define his career. In this small canvas, the walls themselves seem to be made of color and the air of light.