Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to the Painting

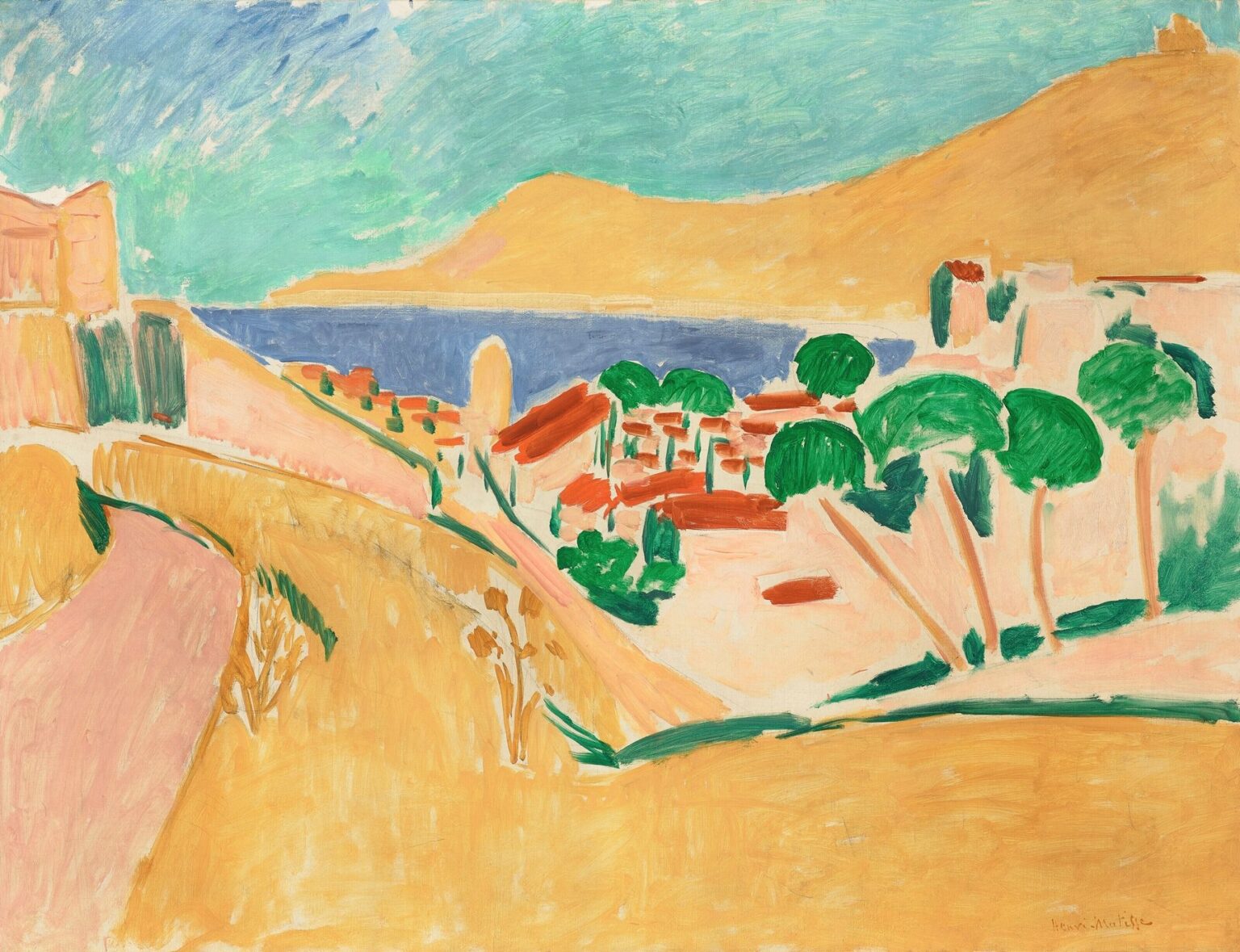

“Collioure in August” is a sun-struck sweep of the Mediterranean turned into pure rhythm. The hills are ochre and apricot, the sea a dense strip of cobalt, the sky a wind-combed turquoise, the trees hard, brilliant greens that sit like bright stones against pale masonry. Houses become planes, streets become ribbons, and the land itself is simplified into wide, tilting facets. Henri Matisse paints not a postcard view but the sensation of standing above Collioure in the dry blaze of late summer and letting color do the work of description.

Collioure and the Fauvist Legacy

Collioure mattered to Matisse. It was here in 1905, painting side by side with André Derain, that he first pushed color to the edge of convention and earned the label “Fauve.” By 1911, when this canvas was made, Fauvism as a movement had ebbed, but its discoveries were alive in Matisse’s practice. The return to Collioure is both literal and artistic: a revisiting of the coastal motif through the lens of new priorities. Instead of the eruptive oppositions of 1905, he now seeks a large, singing order—color harmonies that bind terrain, water, and town into a single chord.

A High Vantage and the Sweep of Space

The viewpoint is elevated, as if the painter stood on a road rising above the village. That height allows the picture to fan outward in a wide arc: foreground slope, descending road at left, a wedge of roofs and trees in the middle distance, the strong horizontal of the sea, and amber hills beyond. The horizon sits high enough to turn the lower two-thirds of the canvas into an amphitheater of land, encouraging the eye to travel in big gestures rather than to fuss over incident. Space is deep, but it is constructed by color zones and sweeping edges, not by linear perspective.

Composition as Interlocking Planes

The landscape resolves into interlocking planes that read like pieces in a calm puzzle. At left, the road curves down in pink-beige and disappears behind a buttress; a pale ramp of earth drops toward the village; a central blade of land slides toward the sea; and on the right a gold field tilts like a table leaf. These planes meet in clean seams, their joins emphasized by darker strokes of green. The planes are not flat in feeling; they pitch and cant like facets of a crystal, giving the impression of terrain modeled by light rather than by contour lines. Matisse’s genius here is to keep each plane simple while letting their junctions create energy.

The Sea as a Pictorial Anchor

Across the center runs a compact band of blue—the sea compressed into a single, saturated note. That band steadies the composition. Against its cool mass, the hot yellows of the hills and the sharp greens of the trees find their pitch. The sea’s horizontal is the canvas’s metronome; it is the resting line to which all diagonals relate. A thin rim of pale shoreline between land and water prevents merger and gives the eye a breath, like the silence between two phrases in music.

August Light and the Warm Key

The month in the title matters. August in Collioure means dryness and glare, and Matisse sets the entire painting in a warm key. Ochres, apricots, and pale salmon dominate the land, their heat held in check by broad passages of cool sky and water. Instead of building shadows with dark tones, he lowers chroma or slips to a companion hue. The effect is of light that saturates rather than models, bleaching edges and flattening local textures the way Mediterranean sun does at noon. The viewer feels heat as color rather than as narrative.

Architectures of Green

The trees are not botanical portraits; they are firm, circular masses of green set atop sandy trunks that lean and gather like dancers. Their simplified caps, especially along the right side of the canvas, act as a counter-rhythm to the warm planes of land. Green also threads through the picture as a structural accent: a dark stroke along a path, a thin band edging a hill, a smear that marks a garden beside a roof. These touches create an invisible frame that holds the peach and gold fields in place. The complementary relation of red-orange roofs to green canopies gives the village its pulse.

Red Roofs as Beats of Tempo

Dashes of terra-cotta roofs cluster in the village center and then echo outward in smaller flags. They are beats of tempo in the composition, quick warm notes that prevent the eye from slipping too quickly across the pale buildings. Because the palette elsewhere is so open, each roof spot is decisive. The red is neither naturalistic nor arbitrary; it is constructive, chosen to balance the chromatic climate and to articulate the rhythm of settlement within landscape.

Drawing with the Brush

Contour in this painting is painted, not drawn. Matisse uses the edge of a loaded brush to make clean, dark-green seams where planes meet. Elsewhere he lays broad swathes in parallel passes that leave the trace of bristles. The result is a drawing that belongs to painting: lines thicken into strokes; strokes widen into planes. In places—especially in the sky—strokes slant, curl, and cross, lending movement to what might otherwise be inert zones. The picture reads up close as a choreography of brush decisions and from afar as a serene map of color.

The Sky as Active Field

The sky contributes more than color balance. It is painted in diagonal, interleaving strokes of turquoise and mint that flicker against one another, a visual breeze that lifts the painting’s top edge. These visible strokes also echo the leaning trees on the right and the curved road at left, so that no area feels isolated. The sky is not a passive background; it is an active field that completes the rhythm begun by the land.

Simplification Without Emptiness

The canvas famously looks simple. Houses dissolve into planes, walls into pale rectangles, hills into large fields. Yet nothing feels empty. The simplification works because each area has internal life: the land’s ochres vary slightly; the sea contains a quiet variation of blue; the sky’s strokes interlock; the trees carry directional marks. Simplification here is a discipline that prunes description down to essential relations. The viewer’s mind supplies the rest—texture, noise, heat—while the eye drinks the clarity.

Mediterranean Geometry and Memory

“Collioure in August” reads as an image seen and an image remembered. The actual topography is recognizable—the amphitheater of hills sliding to the port—but Matisse pulls it toward geometry. Hills become triangles and trapezoids, trees become disks on stalks, streets and paths become ribbons. The relation of parts matters more than the anecdotal charm of fishing boats or figures. This is how memory sorts a place: by big shapes, striking colors, and the lay of lines. The painting therefore feels at once immediate and archetypal, a Collioure that stands for all bright Mediterranean towns.

The Decorative Vision and What Came Next

The year 1911 sits between the monumental experiments of “Dance” and “Music” and the Moroccan journeys of 1912–1913. In those large canvases, Matisse explored how flat color fields could carry intense feeling; in Morocco he would explore patterned light and architectural calm. “Collioure in August” gathers these threads in landscape form. It treats the world as a decorative order—planes that fit, colors that chord, rhythms that repeat—without losing outdoor air. One can sense the path toward the airy Nice interiors of the early 1920s, where similar logics would govern screens, shutters, and fabrics inside a room.

The Role of the White Ground

In many passages the pale ground of the canvas or a thin underpaint peeks through. Around buildings it acts as sunlit mortar; along edges it becomes a thin glint of light; within the sky it cools turquoise into breath. Leaving that ground visible keeps the picture from clogging with pigment and intensifies the feeling of heat. It is also a frank admission of process: the artist blocks in, adjusts, and decides what to complete and what to let breathe.

Movement and Stability

The composition balances sweep and stillness. Sweeping curves—the road at left, the scythe-like edge of the central slope, the long coastal hill across the water—carry the eye along wide arcs. Against these, the sea’s horizontal, the vertical trunks of the right-hand trees, and the blocky profiles of buildings provide anchors. The eye alternates between gliding and pausing, an optical analogue to walking a hillside path and stopping to look.

Temperature and Texture

Matisse weighs not only hue but temperature. Warm ochres and apricots dominate the land; cool mints and blue-greens refresh the upper air; dense cobalt cools the middle band. The paint is generally thin, spread with visible bristle paths, but certain accents—the green tree caps, the red roofs—are laid a touch thicker, so they catch light and read forward. The tactile contrast is small yet effective. Color and thickness collaborate to sort foreground from middle distance without resorting to conventional shading.

The Human Element Without Figures

There are no people in the scene, yet the painting is full of human presence. The road, walls, rooftops, and gardens announce habitation, and their arrangement suggests a slow daily traffic between hillside and port. The decision to omit figures bolsters the work’s calm graphic order; bodies would break the planes and pull attention into narrative. By keeping activity implied rather than shown, Matisse lets the viewer occupy the space imaginatively.

From Natural Color to Constructive Color

The oranges and greens of this canvas are not local color lifted from the motif. They are constructive—chosen to establish a stable chord in which each note has a job. The sky could have been bluer, the land browner, the trees more varied. Instead Matisse selects a narrow family of clean hues, then assigns them structural roles: green to bind edges and crown trees, orange to map land, red to beat within the village, blue to anchor the center, turquoise to ventilate the top. This constructive color is the enduring lesson of Fauvism, matured here into equilibrium.

Edges as Music

One can listen to this painting through its edges. Along the sea line the land meets water in a relaxed, nearly horizontal consonance. Along the road and central slope, edges sharpen into bright intervals that quicken the pace. Where tree caps overlap houses, broken edges create syncopation. The painting is legible as a score for the eye, its measures set by color joins and directional strokes.

Why the Painting Still Feels Fresh

More than a century later, “Collioure in August” feels unburdened and contemporary. Its confidence in big, clear shapes anticipates later modern landscape abstraction; its reliance on a few keyed hues suits the way we read images today, quickly and at scale. Yet it never abandons place. The Mediterranean remains palpable: heat on stone, a sea band in midday, a village pooled in green shade. The freshness comes from that double fidelity—to sensation and to order.

Conclusion: A Summer Chord Made Visible

Matisse compresses Collioure’s August into a summer chord—ochre land, cobalt sea, turquoise air, green trees, red roofs—tuned so that every part supports the rest. Composition is simplified to the point of clarity without losing atmosphere; brushwork remains candid, airy, and musical; memory and observation fuse. The canvas invites the viewer to rest in its balance, to feel heat as color and distance as plane, and to recognize the Mediterranean not through description but through harmony. It is a landscape one hears as much as one sees.