Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

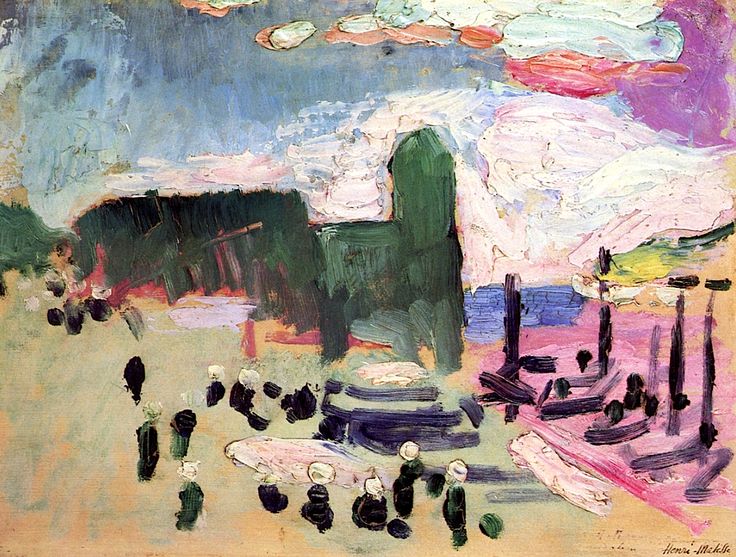

Henri Matisse’s “Collioure” from 1905 is a compact manifesto for everything that would soon be labeled Fauvism. Painted during the seminal summer he spent on the Mediterranean coast with André Derain, the work compresses the town’s harbor, sky, and seafront life into a field of audacious color and impulsive marks. Matisse is not recording topography; he is translating light into pigment and reimagining how a painting can be built. The image looks spontaneous—blocks of emerald and violet, lavender clouds, slips of pink—and yet the orchestration is deliberate. Within this small panel, Matisse tests how far color can carry structure, depth, and mood without the scaffolding of classical drawing. The result is a scene that feels at once coastal and visionary, public and intensely personal, a place seen and a sensation remembered.

Setting and Motif

Collioure, a fishing village wedged between the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean, offered Matisse conditions he had long sought: crystalline light, saturated shadows, and daily life that unfolded near the water’s edge. In this painting the motif is the harbor front with boats riding at their moorings, a queue of masts puncturing the right side of the composition, and a block of dark architecture anchoring the center. The foreground reads as a sandy promenade animated by small, dark figures. These elements give the work its sense of place, but none is described with documentary precision. Each figure is a compact blot with a pearl of white for a hat; each boat collapses into a few horizontal smears; the buildings become masses of paint that serve as color-bearing planes. The subject, ultimately, is not the village but the experience of being in it under a mutable sky.

Compositional Architecture

Matisse builds the scene on a simple but effective scaffold. A diagonal runs from the lower right to the middle ground, created by the berth of boats and the line of mooring posts; this diagonal pulls the viewer inward and simultaneously lifts the eye toward the horizon. The deep green block at center operates as a keystone. It holds the composition against the expansive, windblown sky and gives weight to the otherwise airy field of ground and water. Across the left half of the painting, a low belt of darker shapes counterbalances the verticals of the masts. Matisse thus divides the picture into interlocking zones—ground, crowd, harbor, architecture, sky—without resorting to linear perspective or detailed contour. The orchestration of densities and intervals makes the scene cohere.

Color as Structure and Emotion

Color, not line, drives the composition. The most radical choice is the sky: bands of periwinkle, lilac, and rose recede and overlap, while clouds blush with peach and cool white. These hues have little to do with meteorological accuracy and everything to do with the sensation of light ricocheting off sea and stone. Beneath this sky, the sea is reduced to a chilled strip of violet-blue that sets off the warm, shell-pink sands. The central building is pitched in a deep bottle green that would be unthinkable in academic landscape but proves indispensable here: it welds the middle ground, cools the painting’s temperature, and creates a hinge between the pastel aerial tones and the warmer earth.

The crowd in the foreground is rhythmically marked with inky greens and blues, each capped with a dot of white. The white hat-tops act like visual metronomes across the lower third of the canvas, beats that unify the field. Throughout, complements are made to clash productively: green against pink, violet against yellow, aqua against coral. The emotional effect is buoyant and slightly electric, as if the whole day were charged with salt air.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Part of the painting’s exhilaration comes from the way paint itself is allowed to remain visible. Matisse lays on passages of impasto, especially in the sky and the highlights on the ground, so that the surface catches light like stucco blasted by sun. Elsewhere he scrapes and skids the brush, leaving ragged edges that vibrate against neighboring hues. The boats are little more than pulled strokes; the masts are short, loaded up-and-down touches; the figures are pressure-sensitive ovals. The variety of touch prevents the color fields from feeling static. Each area has its own tempo and grain, and the diversity of handling becomes a kind of narrative: gusts moving through the harbor, voices clustering and dispersing, clouds forming and unraveling.

Space Without Illusionism

There is depth here, but it is gained by color temperature and size cues rather than by measured perspective. Warm, light tones advance; cool, dense tones recede. The tiny figures and compressed boats establish a low horizon without Matisse ever drawing a line. The sky, occupying fully half the composition, acts like a dome pressing toward the viewer, while the heavy green building pushes back. This push–pull creates an elastic space that feels more like lived perception than like a diagram of a place. You experience yourself standing on the quay, looking outward under a sky that seems close and bright, your attention snagged by the press of bodies and the vertical punctuation of masts.

The Role of the Figures

The people in “Collioure” are reduced to signs, and that reduction is poignant. Each is a handful of strokes: a dark torso, a pale hat, a suggestion of legs. The simplification does not erase individuality; instead it emphasizes shared activity, the communal life of the port. Because the figures remain open to interpretation, viewers project themselves into the scene. The painting’s social space is elastic; it can accommodate any passerby. This, too, is part of Matisse’s modernity: he treats public life not as genre anecdote but as a field of sensations in which anyone might participate.

From Divisionism to Fauvism

The painting shows how thoroughly Matisse had absorbed and surpassed Neo-Impressionism. Instead of the tiny, uniform dots of Divisionism, he uses broad, varied marks. Instead of aiming for optical mixture obeying color theory, he orchestrates intuitive harmonies and tensions, trusting the eye rather than a formula. The palette retains the luminosity Divisionism promised, but the method is freer, more responsive to lived time. This freedom is what startled critics at the 1905 Salon d’Automne and earned Matisse and his companions the nickname “Fauves.” “Collioure” makes clear why the label stuck: the color is unbridled, the drawing audaciously abbreviated, and the effect is both raw and exquisitely musical.

Dialogue with “Open Window, Collioure”

Painted the same season, “Open Window, Collioure” is often cited as Fauvism’s emblem. That interior–exterior motif frames the harbor through a window, while “Collioure” places the viewer directly in the open air. The kinship between the two is instructive. In both, the boats are quick patches of saturated pink and blue; in both, water is a sheet of vibrating chroma rather than descriptive ripples. Yet “Collioure” pushes further into abbreviation. The framing device of the window in the other canvas provides a stabilizing geometry; here, the world is stabilized by color alone. The comparison highlights the courage of Matisse’s enterprise: having proven that a window’s frame can hold the explosion of color, he now removes the frame and trusts orchestration to do the job.

Weather, Time of Day, and the Sensation of Air

Nothing in the panel feels heavy. Even the darkest greens are aerated by subsurface flickers of red and violet. The clouds are not fully modeled forms but floating palettes of cool and warm whites that mingle with lavender and peach. This mixture conveys the restless, clarifying atmosphere of the coast, where light is scattered by spray and wind. Matisse’s shifting touches keep the eye moving, making the air almost tactile. You do not “read” the weather; you sense it. It resembles those coastal days when shadow edges blur and color intensifies, when the horizon seems near despite its physical distance.

Drawing with Color and the Courage to Omit

There is almost no linear drawing here. Where outlines do appear—on the top of the central structure, along the masts—they are fragments that prevent the forms from dissolving entirely. The rest is color-drawing: forms come into being as blocks and ribbons of hue abut or overlap. The courage to omit details is as important as the courage to deploy bold color. Matisse leaves out windows, rigging, faces, and stonework. Those absences invite the viewer to supply what is missing, turning looking into an active collaboration. The quickness you feel is not sloppiness but intentional openness.

The Ethics of Pleasure

Matisse’s audacity often gets described as purely formal, but “Collioure” also embodies an ethics. It asserts that pleasure—of sun, sea air, and color—can be a serious artistic subject. The work is not frivolous; it is generous. The warmth of the foreground, the carnival-like scatter of the crowd, and the buoyant sky together argue that a painting may create conditions for well-being simply by arranging colors in a humane way. That conviction will animate the rest of Matisse’s career, from the saturated interiors of the 1910s to the radiant cut-outs of his final decade.

Materiality and Scale

A striking aspect of “Collioure” is its physical smallness relative to its visual amplitude. The scale amplifies the sensation of compression: a harbor day distilled into a few square inches of pigment. Because the surface is not fussed over, its facture reads clearly even at a distance. The brushstrokes are legible, the scraping decisive, the impasto catching actual light in a way that imitates and rivals the painted light. The small panel becomes a stage where color performs with the energy of a mural.

Relationship to Place and Memory

Although the painting was made on site, its most powerful truth is psychological. Collioure is rendered as a mental map of sensations. The monumental green mass is not just a building; it is the feeling of shade after crossing a bright square. The chorus of pale hats is not just a crowd; it is the ripple of social presence. The boats are not just equipment; they are the promise of movement and return. In this sense, the painting anticipates later modernist approaches that regard place as an accumulation of felt events rather than a fixed set of objects.

Influence and Reception

Works like “Collioure” helped license an entire generation of painters to prioritize color and sensation. Derain, Vlaminck, and Braque each responded to the Mediterranean light with increased chromatic daring after witnessing Matisse’s approach. The painting’s economy of means also proved influential. One could enunciate a world with a few strokes if those strokes were decisive and relationally sound. That is a lesson that echoes from German Expressionism to postwar abstraction and into contemporary painting’s appetite for abbreviated figuration.

Ways of Looking

Spending time with the picture yields rewards that a quick glance misses. If you begin at the lower right corner, the pink ground and pale violet boats form a pathway into the scene; follow that path and you will feel the pull of the harbor’s diagonal. Let your gaze rest on the green mass at center and notice how it keeps the neighboring colors from scattering. Move into the sky and watch how small shifts between lilac and blue suggest currents of air. Slip back down to the crowd and register the pattern of white hat-tops as a counter-rhythm to the vertical masts. This moving attention reenacts the painting’s own making: a sequence of decisions tested against sensation.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Place this panel near the more detailed harbor scenes of 1904 from Saint-Tropez and you can track the acceleration of Matisse’s thinking. The earlier works, while experimental, still model forms and stage a stable horizon. “Collioure” strips away those props. Place it next to the later “View of Notre-Dame” canvases and you see how the Collioure logic migrates to Paris: architecture dissolves into zones of color; the city’s air is rendered in mauve and jade. The through-line is a commitment to building space with hue and interval rather than with academic drawing.

Light, Shadow, and the Invention of Value

Traditional value modeling uses black and white to create gradations of light and shadow. Here, value is invented chromatically. The shadowed sides of forms are achieved with cool greens and purples; highlights are infusions of pale pink and thick white. The result is a picture that reads as sun-struck without any brown shadows or black accents weighing it down. This approach clarifies why Fauvist color still feels fresh: by refusing earth tones as the default path to shadow, Matisse keeps the painting’s energy near the surface.

Memory of the Human Hand

The paint handling in “Collioure” foregrounds the hand’s intelligence. You can reconstruct the order of operations: sky first in broad fields; green mass dropped in wet-on-dry so its edges hold; figures flicked in last like notes on a staff. Seeing the sequence is not an academic exercise; it deepens empathy with the act of making. The marks are not anonymous. They are signatures of attention, and the viewer’s eye becomes a witness to decisions. This is one source of the painting’s intimacy despite its public subject.

Conclusion

“Collioure” condenses a pivotal summer into a blazing argument for color’s sovereignty. In a small harbor view Matisse reimagines what a landscape can do. He dispenses with minute detail, relies on bold blocks of hue, and organizes space through temperature, saturation, and rhythm. The scene remains rooted in the world—boats, a crowd, the crush of buildings and sky—but it is transfigured by a sensibility that prizes sensation over description. The painting is generous in spirit and radical in method, a pageant of light that still feels modern because it continues to trust the viewer’s capacity to complete the world from vivid signs. To stand before it is to feel the Mediterranean brightness unspool through color, to sense the sea breeze moving the clouds, and to recognize in those abbreviated figures the shared pleasure of simply being out in the day.