Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

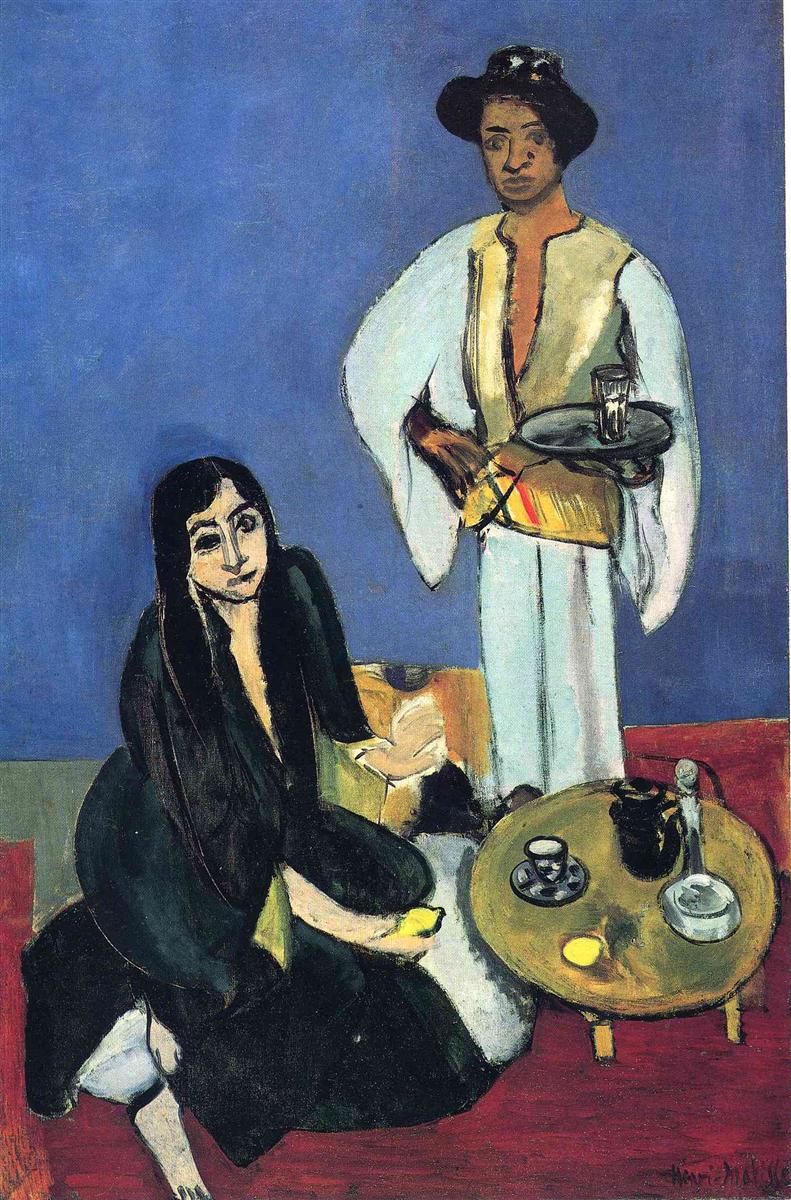

Henri Matisse’s “Coffee” (1916) stages a ritual of hospitality with the economy and force of a modern icon. A young server in a flowing, light tunic stands against an oceanic wall of blue, balancing a round tray and glass. Beside him, a woman in deep black crouches on a red floor, her gaze meeting ours while her hand rests near a small lemon. A low ocher table between them carries a black pot, two cups and saucers, and a clear carafe. The room is distilled to a few colored planes—blue for the wall, red for the floor, a cool greenish rectangle for a mat or cushion—so that the quiet drama among people and objects reads with maximum clarity. The scene is simple; the painting is not. “Coffee” compresses Matisse’s years of looking—Fauvist color, Moroccan motifs, and his wartime discipline—into a poised conversation about line, plane, and human presence.

Historical Context

“Coffee” belongs to Matisse’s austere, searching period from 1914 to 1917. The hedonistic blaze of Fauvism had cooled; Paris was at war; and the artist, who had recently returned from North Africa, was paring his language to essentials. In these years he painted windows as gridded abstractions, portraits as masklike presences, and still lifes reduced to calibrated planes. Yet he never abandoned color. Instead, he used strong hues sparingly, assigning whole areas—the blue wall, the red floor—to single, unwavering notes. “Coffee” absorbs memories from Tangier and Tétouan—ceremonial serving, low tables, draped garments—while adopting the structural rigor of his wartime canvases. The result is at once intimate and monumental.

First Impressions

From a distance, the picture organizes itself into a small architecture. The standing figure provides a vertical column; the seated figure forms a dark triangle on the floor; and the round tabletop offers a countering circle. The background is a vast, breathable blue that makes the people feel sculptural. The palette centers around four strong notes—blue, red, black, and ocher—supported by pale greens and creams in the garments and carpet. Matisse’s black contour stitches everything together, thickening where he wants weight and thinning where he wants openness. Nothing is fussy, yet the scene feels fully furnished.

Composition as Theater

Matisse composes the canvas like a quiet stage. The standing server and the seated woman create a two-figure arrangement that locks into the rectangle. The server’s body is nearly centered, stabilizing the picture, while the woman’s diagonals pull leftward and downward, energizing the lower half. The circular table interrupts the verticals and diagonals with a steady, low horizon. Its top is slightly tilted, a typical Matisse device that clarifies placement without resorting to elaborate perspective. The tray in the man’s hand mirrors the table’s circle, linking the two halves of the room. Even small items are compositional actors: the lemon on the table and the one near the woman repeat a yellow accent that keeps the eye moving along a gentle arc.

The Language of Color

The color system is both reduced and expressive. The wall is a broad field of saturated blue that functions like daylight made solid. It is neither sky nor interior paint; it is a climate. The red floor is not the local color of any specific carpet; it is warmth embodied. The server’s tunic, painted in mint and cream with a golden sash, opens a cool vertical that freshens the hot floor; his dark hat picks up the black outlines that score the picture. The woman’s black garment is a deep well that concentrates value and attention, but flashes of pale skin, a cream cushion, and a lemon prevent the black from swallowing the lower left. On the table, ocher wood and black pot assert a sober, earthy register that secures the scene. The palette is simple enough to memorize, but the intervals between colors are subtle, producing harmony without monotony.

Drawing and the Authority of Contour

Matisse’s drawing is the painting’s skeleton. He uses an elastic black line to articulate shoulders, sleeves, tray edge, coffee cups, and faces. The line thickens around the woman’s hair and the curve of the table, thins along the server’s forearm, and breaks lightly where the tunic meets the blue wall. This modulation gives each material a different “voice.” The faces are constructed with only a few strokes—arched brows, an angled nose, a hint of lips—yet they register emotion. The seated woman’s head tilts with a mixture of attentiveness and fatigue; the server’s gaze is steady, almost ceremonial. The force of contour lets Matisse model minimally. A handful of interior strokes—an ocher sash, a shadow along a sleeve, a crescent at a cheek—are enough to suggest volume.

The Figures: Roles and Relationships

The standing figure reads as host or attendant, his posture formalized by the upright tray. His tunic’s wide sleeves and sash give him a fluttering silhouette that contrasts with the seated woman’s dense pyramid of black. Though he is centered, his body turns toward her in a subtle bow. The woman, one knee tucked under, one foot extended, holds a small fruit and leans forward as if mid-conversation or mid-reach. Her face, ringed in black hair, meets the viewer’s eyes with a frank, almost theatrical look. Their relation is balanced but not symmetrical: service and reception on the one hand, attention and invitation on the other. The coffee ritual joins them in a shared act rather than separating them into hierarchies.

Objects as Protagonists

The low round table is not furniture alone; it is the third protagonist. Its top carries a black pot, two cups and saucers, and a clear carafe whose pale contents catch the wall’s blue as glints of milky light. Matisse resists precise labels—these could be coffee, tea, or water—because he wants objects to function as shapes and weights first. The duplication of circular forms—the tray, cups, saucers, carafe base, table—creates a constellation of rounds that steadies the picture. The lemons are bright interrupters, small suns that punctuate the ocher plane and then echo at the woman’s hand. Their color also bridges the table to the sash around the server’s waist, tying forms and persons into one decorative system.

Light and Value

Light is redistributed to clarify relations rather than to imitate a single source. The wall holds a middle value; the floor is darker; the table is lighter; the figures each carry their own value structure. On the woman’s face, the highest lights sharpen her glance; in the server’s tunic, pale strokes trace folds and sleeve edges so the garment breathes. The black garment and pot provide the deepest values, giving the composition its anchor. The glassware is solved with quick, transparent strokes and small highlights, enough to convince without seducing the eye away from the whole.

Brushwork and Surface

The paint is alive. In the blue wall, strokes move horizontally and diagonally, leaving a faint weave that prevents flatness. The red floor is brushed more densely along the front edge, where Matisse wants weight. The garments alternate between thin, washy passages—where the blue seems to show through the white—and firmer, impasted accents at seams and cuffs. Around the table’s rim and the tray’s edge, he drags the brush to create a slight ridge that catches light just as a metal lip might. This variety of touch lets different materials announce themselves without descriptive fuss.

Space, Depth, and the Tilted Stage

“Coffee” compresses depth to a shallow stage. The horizon where floor meets wall is low; the table is tipped forward; the seated figure sits on a cushion that reads as a trapezoid of cool green. Overlap handles the rest: the woman overlaps the floor and cushion; the table overlaps her knee; the standing figure stands between table and wall. There are few cast shadows. This deliberate compression keeps the painting decorative, ensures the surface remains present, and allows relationships of color and contour to carry the narrative.

Morocco Remembered, Not Illustrated

Matisse’s North African experiences surface in the scene’s details—the low table, citrus, glass carafe, and flowing garments—yet nothing is ethnographic. The clothes are generalized; the interior could be a studio arranged with props rather than a specific café. What matters is the atmosphere of ceremony and leisure, the gesture of serving and receiving. Matisse distills what charmed him in cafés and houses abroad—the grace of pouring, the rhythm of conversation, the dignity of the host—and rephrases it in the spare language of his wartime images.

The Psychology of Color

Color carries emotion without melodrama. The blue wall cools the room and quiets the mind. It is a contemplative backdrop against which the faces become legible. The red floor is bodily and warm; it animates the lower half and highlights the crouched pose. The ocher table reads as earth and grain, grounding the ceremony. Black is not a void here; it is authority. The woman’s dress, the coffee pot, and the outlines together lend gravity to an otherwise airy palette. The little lemons are witty flashes of wit and wakefulness—appropriate to a picture about coffee.

Rhythm and Repetition

The painting is bound by a web of repeating shapes and colors. Round echoes are everywhere, from tray to table to cups to lemon to carafe. Yellow repeats in sash and fruit. Black jumps from pot to hair to garment to hat to outline. These echoes are not cosmetic; they create rhythm. The viewer’s eye circulates, never stranded, always offered a path from one form to the next. That sense of circulation mirrors the theme: the poured beverage, the passed tray, the turn of conversation.

Evidence of Process

Look closely and the history of the painting shows through. There are faint haloes where the server’s arm or the table edge was shifted. The blue wall contains thin places where a warmer ground appears, testimony to the artist’s adjustments. The woman’s extended foot bears a ghost line beneath its final contour. These pentimenti are the record of looking and deciding. They keep the painting human and resist the illusion of effortless finish.

Comparisons within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Coffee” speaks to the portrait “The Italian Woman” (1916) in its masklike face and restricted palette; to “Sculpture and Vase of Ivy” in its reliance on a few large planes and a tabletop ritual; and to the 1913 Moroccan works in its fascination with costume and hospitality. Yet it is more intimate than the grand “Bathers by a River,” more narrative than the pure still lifes, and more architecturally calm than the lush 1913 interiors. As a node among these works, it demonstrates Matisse’s capacity to keep color generous while holding design under strict control.

How to Look

Begin with the whole: feel the blue wall’s quiet, the red floor’s heat, and the two figures’ differing stances. Let your eye loop the circles—tray, table, cups—and then settle on the two lemons, one by the woman’s hand and one on the table, as small beacons. Move to the faces; note how few strokes carry expression. Step closer to watch the paint in the tunic’s sleeves thin to a veil and the carafe’s glass surface catch a zigzag of light. Step back again until people and objects settle into an emblem of hospitality. The pleasure of “Coffee” lies in this oscillation between decorative order and human detail.

What the Painting Offers Today

A century later, “Coffee” feels unexpectedly contemporary. Its color-blocked planes anticipate graphic design; its black contours echo print and comics; its pared-down objects read like icons on a screen. Yet the painting’s humanity remains. The ritual of serving a drink, the pause of company, the small brightness of citrus—these are universal. Matisse’s achievement is to make that universality legible in the fewest possible terms, so that each stroke matters and each color holds its own meaning.

Conclusion

“Coffee” distills Matisse’s art into an intimate scene where color, line, and everyday ritual align. A blue wall and red floor make a chamber of calm and warmth; a low table gathers objects that invite touch; two figures—one upright, one kneeling—compose a respectful duet. The black pot promises aroma; the lemons sparkle; the carafe and glass catch light. The painting feels poised, deliberate, and humane. It proves that a modern picture can be both decorative and profound, both economical and alive. In a period of upheaval, Matisse found clarity not in grand narratives but in the small theater of hospitality. That clarity is why “Coffee” still invites us to sit, look, and share the moment.