Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

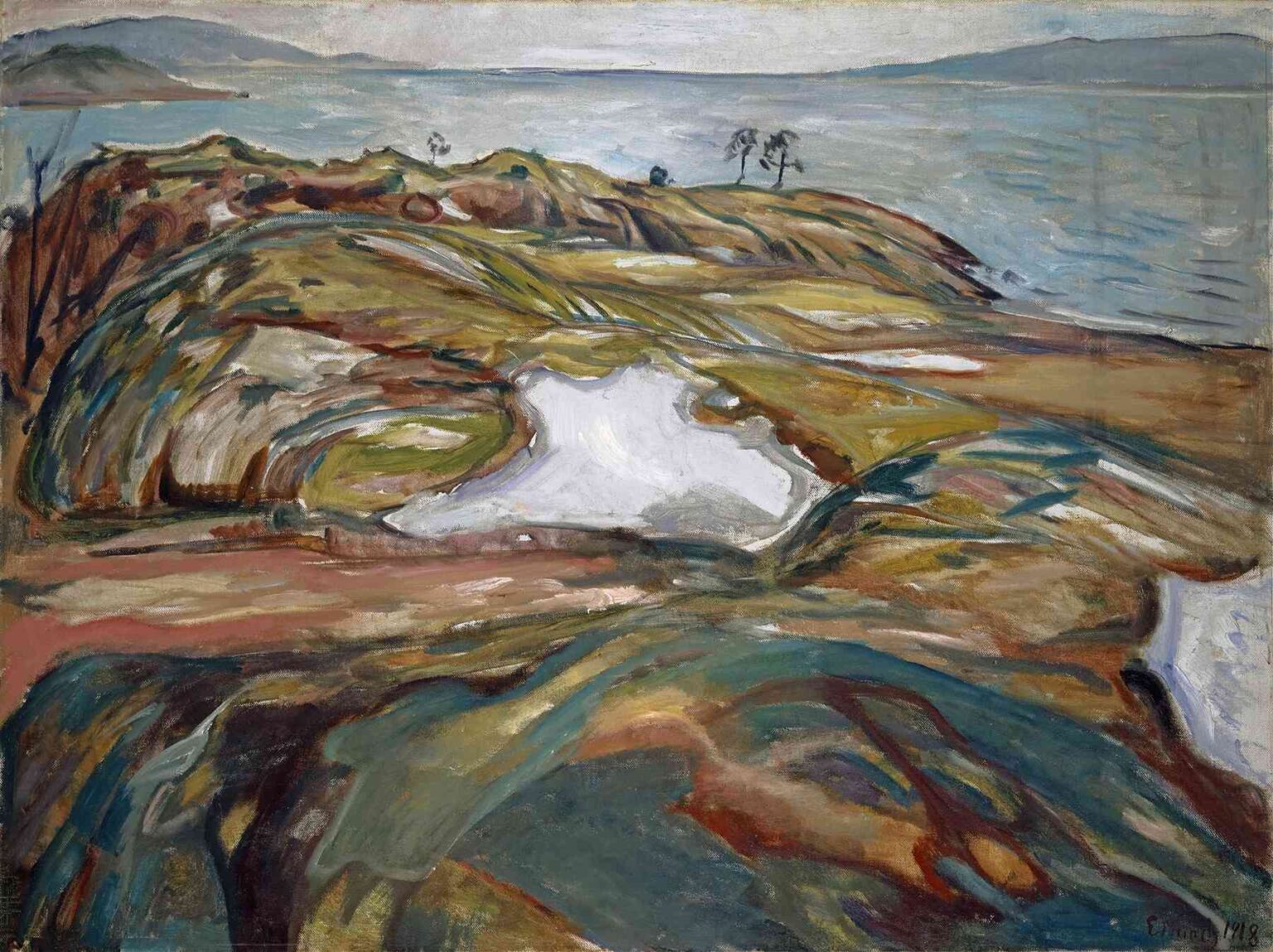

Edvard Munch’s Coastal Landscape (1918) is a striking example of the artist’s late-career engagement with nature’s elemental forces. Painted shortly after World War I, this oil on canvas captures a rugged shoreline at Åsgårdstrand—the seaside village that inspired Munch throughout his life. With its sweeping views of undulating rock formations, pale fjord waters, and distant hills, the composition conveys both the physical contours of Norway’s coast and the emotional undercurrents of change, renewal, and the passage of time. Through a dynamic interplay of form, color, and brushwork, Munch transforms a topographical scene into an expressive meditation on landscape as mirror to human feeling.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1918, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) had lived through profound personal and global upheavals. The early loss of his mother and sister had long informed his artistic exploration of grief and anxiety. In the decades leading up to World War I, Munch split his time between Norway and Germany, contributing to the Berlin Secession and influencing emerging Expressionist circles. The war’s devastation prompted Munch to return to Norway and seek solace in familiar landscapes. Coastal Landscape was painted at Åsgårdstrand, where he spent summers sketching vistas of rocky promontories and shimmering water. This setting held personal resonance: it was where he first painted “The Scream” in 1893 and where he revisited themes of solitude and transformation throughout his career.

Composition and Spatial Structure

In Coastal Landscape, Munch constructs a layered spatial design that guides the viewer’s eye from foreground to horizon. The foreground is dominated by sweeping arcs of exposed bedrock, rendered in fluid, sinuous strokes that suggest both geological solidity and organic movement. A central ledge—bleached white by sun and salt—leads the eye toward the middle ground, where ridges of green-tinged cliffs slope gently down to the fjord’s edge. Beyond, the placid blue-gray waters extend to a far-off shoreline under a pale, overcast sky. Munch’s horizon line sits high, compressing the composition and emphasizing the rocky forms below. This elevated perspective fosters a sense of vastness without sacrificing intimacy; the viewer feels both immersed in the immediate textures and aware of the scene’s expansive scope.

Color Palette and Atmospheric Effects

Munch’s palette for Coastal Landscape is at once naturalistic and expressive. Earthy ochres, warm sepias, and muted greens delineate the rocks, while soft grays and silvery blues capture the water’s reflective surface. The sky—painted with thin, translucent layers—shifts from warm ivory at the horizon to cooler grays overhead, evoking a late-afternoon light under shifting clouds. Munch applied pigments in wet-on-wet passages and drybrush touches, allowing colors to blend on the canvas and yield a shimmering, atmospheric quality. Small accents of brighter turquoise and coral hint at lichen-covered stones and sunlit rills. Through subtle tonal modulations, Munch conveys the coastal environment’s ever-changing luminosity, where light dances on rock and water in fleeting patterns.

Brushwork and Painterly Technique

Munch’s brushwork in Coastal Landscape is both spontaneous and controlled. In the foreground, broad, gestural strokes map the rock strata’s curves and fissures; these strokes carry the texture of the paint itself, with ridges and valleys of impasto recalling the stone’s rough surface. In contrast, the fjord’s water is rendered with horizontal, scumbled strokes that suggest gentle waves and reflective shimmer. The distant hills and sky feature thinner washes, their smooth surfaces providing a calm counterpoint to the textured rocks. Munch’s hand remains visible throughout: he rarely blends strokes to invisibility, allowing each brush mark to contribute to the overall rhythmic pattern. This painterly immediacy reinforces the landscape’s vitality, as if the scene were being observed and recorded in real time.

Symbolism and Interpretive Themes

While Coastal Landscape appears as a straightforward plein-air painting, it carries deeper symbolic resonances typical of Munch’s work. The rocky foreground can be read as an emblem of permanence and endurance, standing firm against the flux of tides and time. The pale ledge at center recalls a natural altar or stage, inviting viewers to ponder life’s thresholds—between land and sea, past and future, stability and transformation. The placid fjord suggests introspection and the unconscious, its placid surface hinting at hidden depths. Munch often used coastal imagery to explore themes of birth, death, and renewal; here, the sun-bleached rock and quiet water evoke both the sun’s life-giving warmth and the inevitability of erosion and change.

Psychological Dimensions

Munch believed that landscapes could mirror internal emotional states, and Coastal Landscape is no exception. The dynamic curves of the rock formations seem to pulse with an inner life, while the distant horizon conveys a sense of longing or anticipation. The painting’s high horizon and compressed space can induce a feeling of gentle vertigo, a reminder of human smallness before nature’s scale. At the same time, the careful delineation of forms fosters a sense of order and coherence, suggesting that amid change, stability can be found. In this way, the painting visualizes the balance between anxiety and calm, an emotional dialectic that runs through Munch’s oeuvre—from his anguished figure studies to his serene yet introspective landscapes.

Relation to Munch’s Oeuvre

Coastal Landscape occupies a significant place in Munch’s later career, linking back to his early waterfront motifs and foreshadowing his subsequent late-period abstractions. In the 1890s, landscapes such as Moonlight (1896) and Evening on Karl Johan (1892) explored nighttime atmospheres; in the 1910s, Munch returned to sunlit coastlines, focusing on midday light and geological forms. The fluid brushwork and emphasis on atmospheric tone in Coastal Landscape anticipate his final years, when he would experiment with bolder abstraction and freer handling of paint. The painting also echoes his woodcuts—where he used linear rhythms to suggest waves and cliffs—but here translated into a richly colored, painterly medium.

Reception and Critical Legacy

When exhibited in Kristiania salons and Berlin galleries, Coastal Landscape drew praise for its vibrant handling of seaside scenery and its emotional depth. Critics noted Munch’s ability to combine naturalistic observation with expressive brushwork, a hallmark that set him apart from both academic realists and abstract modernists. Throughout the 20th century, the painting has been included in retrospectives that trace Munch’s lifelong dialogue with landscape: from figurative shores haunted by existential figures to pure nature studies suffused with inner resonance. Scholars have highlighted Coastal Landscape as a key example of how Munch returned repeatedly to the same locales—in this case, Åsgårdstrand—to explore evolving psychological and stylistic concerns.

Conservation and Provenance

Coastal Landscape is held by the Munch Museum in Oslo, where it has undergone careful conservation to preserve its subtle layers of paint and delicate impasto. Analysis of paint cross-sections and infrared imaging has revealed Munch’s layered approach: initial thin washes established basic forms, followed by thicker passages defining rock strata. Conservationists emphasize stable humidity and controlled light to prevent fading in the pale sky and maintain the vibrancy of earth tones. Provenance records trace the painting from Munch’s studio to private collectors and finally to the museum’s holdings in the mid-20th century, reflecting its status as a pivotal work in his landscape corpus.

Broader Cultural Significance

Beyond its place in art history, Coastal Landscape resonates with contemporary audiences for its depiction of a universal meeting point between land and water. Its sweeping forms and nuanced light studies have inspired writers, filmmakers, and poets exploring themes of transition and renewal. In environmental discourse, the painting serves as a reminder of the fragility and resilience of coastal ecosystems, its weathered rocks and calm waters speaking to both natural beauty and climate’s impact over time. The painting’s rhythmic brushwork and harmonious palette continue to influence landscape painters and illustrators, who cite Munch’s ability to capture both the physical and emotional essence of place.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch’s Coastal Landscape (1918) stands as a testament to his lifelong engagement with the interplay of nature and emotion. Through a masterful combination of composition, color harmony, and dynamic brushwork, Munch transforms a familiar Norwegian coastline into a canvas of psychological depth and symbolic resonance. The painting’s layered forms—undulating rocks, reflective water, and expansive sky—invite viewers to contemplate permanence and change, solitude and connection. As both a landmark in Munch’s landscape repertoire and a timeless meditation on the natural world’s capacity to mirror human feeling, Coastal Landscape continues to captivate and inspire audiences more than a century after its creation.