Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to “Clarification”

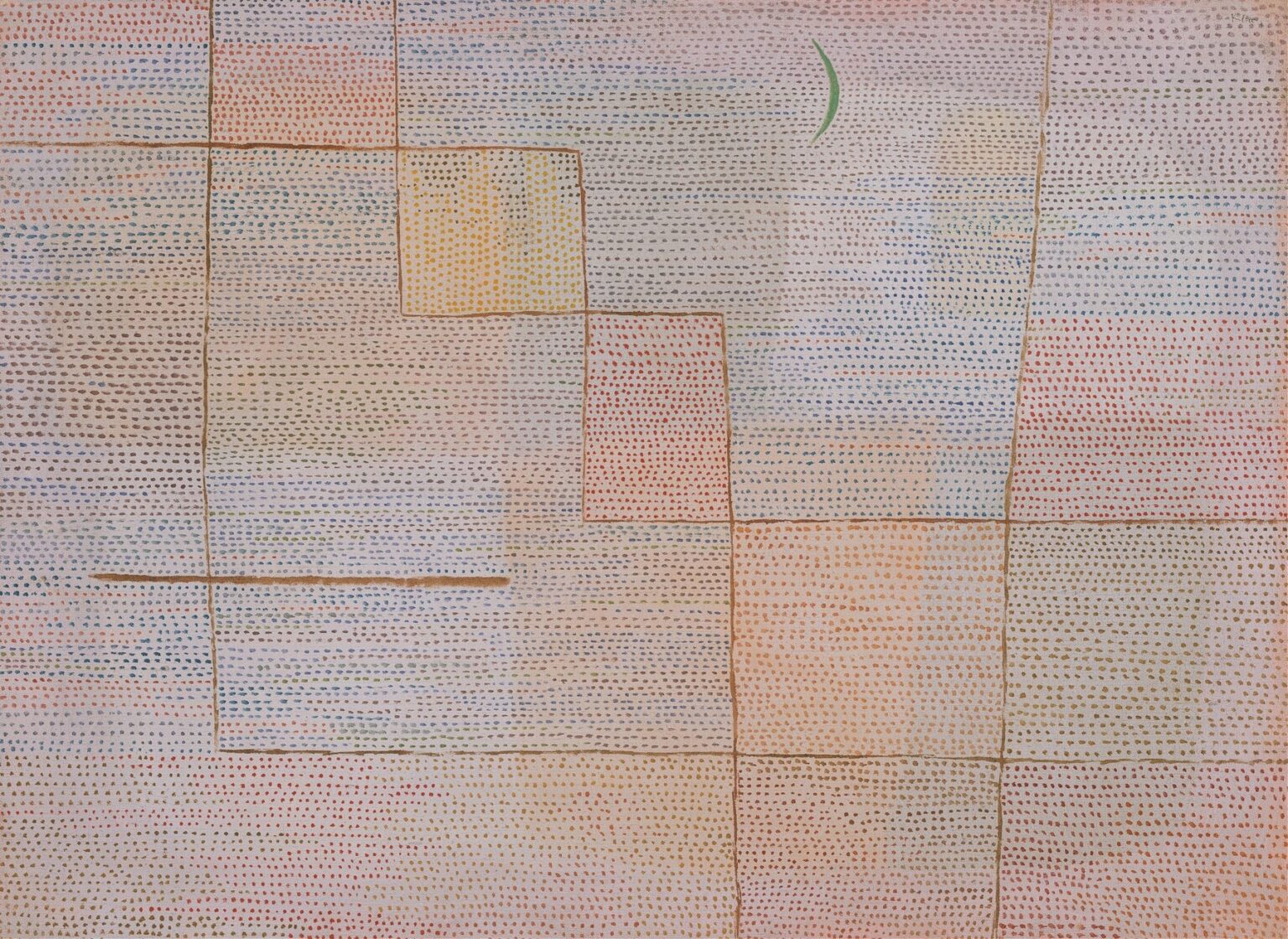

Paul Klee’s Clarification (1932) is a testament to his lifelong exploration of the interplay between color, form, and the invisible structures that underlie perception. Executed as a delicate array of tiny, rhythmic dots and softly outlined rectilinear shapes, this work transcends mere decorative patterning to become a meditation on insight, structure, and the process of seeing itself. In Clarification, Klee invites viewers into a space where color fields merge with suggested architectural grids, and where a single crescent shape introduces a lyrical counterpoint to the overall rectilinear logic. Through a detailed analysis of historical context, formal composition, color theory, symbolic meaning, and technical execution, we can appreciate how Clarification embodies Klee’s conviction that art can render the unseen forces of clarity and understanding visible.

Historical Context and Bauhaus Influence

By 1932, when Klee painted Clarification, he was a tenured master at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany. The Bauhaus principles—unity of art, craft, and technology—had steered Klee toward synthesizing theoretical rigor with poetic expression. Europe in the early 1930s was riven by political turmoil and economic hardship, yet the Bauhaus remained a haven for experimental pedagogy. Klee, inspired by Kandinsky’s teachings on abstraction and by the school’s emphasis on basic visual elements, was refining his own theoretical framework: the relationship of point, line, and plane. Clarification can be seen as a late expression of these ideas, integrating his earlier forays into pointillism and grid-based abstraction with his mature, deeply reflective approach to visual form.

Paul Klee’s Artistic Evolution

Paul Klee’s career spanned caricature, Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and geometric abstraction. Early work displayed playful figuration and sharp satire; later, after his travels to Tunisia in 1914, his use of color became more luminous and structured. By the 1920s, Klee had developed his “point and line to plane” theory, which he elaborated in lectures at the Bauhaus. He described the “point” as the generator of surface, the “line” as the path of the point, and the “plane” as the resulting field. In Clarification, the tiny colored dots function as proliferating points, while the subtle pencil or brush lines delineate a rectilinear network, and the overall composition reads as a unified field in which the dynamic relationship among these elements is rendered legible.

Formal Composition and Spatial Organization

At first glance, Clarification resembles a patchwork quilt composed of rectangular cells, each filled with meticulously placed dots of color. Composed of five vertical columns and multiple horizontal rows, the grid is irregular yet harmonious, with some rectangles subtly larger or smaller. Each cell appears delineated by a light ochre or sienna line, which is so fine that it almost dematerializes, making the border between cells at once palpable and elusive. A single thin horizontal line near the midline slices across the composition, injecting a note of tension into the vertical grid. Above this line, in the upper right quadrant, a slender green crescent arcs gracefully, interrupting the visual regularity with a shape that suggests both moon and leaf.

Color Palette and Pointillist Resonance

Klee’s use of color in Clarification is at once restrained and infinitely varied. The background field shifts from soft pinks and peach tones to pale lavenders and neutral grays, produced by the overlay of countless tiny dots in complementary and analogous hues. In each cell, Klee alternates dot colors—bowed purple, muted red, golden ochre, pale olive, and light blue—to create subtle chromatic vibrations. The result is an optical interplay: from a distance, the dots cohere into harmonious color planes; up close, they reveal their individual warmth and coolness. This pointillist resonance recalls Georges Seurat’s Divisionism, yet Klee’s dots are freer, applied in irregular rows rather than rigid clusters, underscoring his belief in the expressive possibilities of chance within structure.

The Role of the Crescent Form

The solitary green crescent hovering in the upper right quadrant of Clarification functions as a poetic counterpoint to the systemic grid. Its curved shape, oriented like a rising moon, introduces a quiet narrative tension: the cyclical passage of time, the waxing and waning of understanding, and the momentary clarity that breaks through ordered thought. Rendered in a single, uniform green stroke, the crescent stands out against the dusty background, suggesting growth, renewal, or the gentle emergence of insight. Its asymmetrical placement prevents the composition from becoming too rigidly symmetrical, while its organic contour reminds viewers of the cyclical rhythms inherent in nature and cognition.

Symbolic Resonances of Grid and Dot

For Paul Klee, the grid was more than a compositional device; it symbolized order, logic, and the structural scaffolding of perception. The dots, in turn, represented the elemental units of sense: discrete moments of awareness or particles of thought. In Clarification, the interplay between grid and dot can be read allegorically as the process of clarifying complex ideas into digestible units, or conversely, of seeing how discrete observations coalesce into a coherent whole. The grid offers boundaries and orientation, while the dot patterns within each cell suggest the diversity of content that clarity must organize. Together they enact a visual metaphor for Klee’s pedagogy: that true understanding requires both structure and attention to detail.

Technical Execution and Medium

Clarification is executed on paper with watercolor and gouache, combined with a fine brush or pen for the cell outlines. Klee likely began by lightly marking a grid in pencil, then applied washes of watercolor to establish a tonal background. Once dry, he used gouache or more opaque watercolor to dot each cell row by row, perhaps aided by a ruler or guide for spacing. The cell borders were drawn in a diluted ochre or sienna pigment, ensuring they were visible yet unobtrusive. The green crescent was added last, with a steady hand and a richly pigmented gouache. The painstaking layering and careful pacing required for this work reveal Klee’s deep commitment to methodical yet expressive process.

Relationship to Klee’s Theoretical Writings

In his lectures compiled as the Pedagogical Sketchbook (published 1925), Klee emphasized that “taking a line for a walk” and “making a dot into a plane” were fundamental exercises. Clarification demonstrates both principles: the border lines chart the “walk” of the line, tracing the grid; the multicolored dots convert discrete marks into vibrant, unified planes. Klee also wrote about “visual music,” the idea that painting, like music, unfolds in time through rhythmic variation. The dotted patterns in Clarification function like musical notes, each cell a measure in the painting’s larger composition. The horizontal bisecting line echoes a musical cadence, momentarily pausing the vertical flow to let the viewer “hear” the color.

Viewer Engagement and Cognitive Process

Unlike more figurative works, Clarification does not narrate a story or depict recognizable objects. Instead, it invites viewers into an active process of pattern recognition and color perception. The eye moves across the grid, picking up rhythmic variations, subtle color shifts, and the surprise of the green crescent. Each viewer’s experience of clarity may differ: some may focus on the cell arrangements, others on the dot colors, and still others on the shape that emerges when multiple cells are perceived as a group. In this way, the painting enacts its own theme, illustrating how clarification is a subjective, constructive act that depends on attentive engagement.

Comparative Analysis with Contemporary Abstraction

While many modernists embraced bold, gestural abstraction in the 1930s, Klee pursued a more introspective path grounded in systematic exploration. Clarification contrasts with Kandinsky’s swirling compositions or Mondrian’s strict Neoplastic grids by forging a middle ground: a structured framework enlivened by playful, varied pointillist dots. Compared to Malevich’s stark Suprematist canvases, Klee’s work retains a warmth and lyricism, underlined by his sensitivity to color nuance. This tension between order and spontaneity positions Clarification as a distinctive contribution to early twentieth-century abstraction, one that influenced later color-field painters and minimalist artists exploring the dialectic of system and serendipity.

Conservation and Display Considerations

Watercolor and gouache on paper present unique conservation challenges, as pigments may fade and paper can oxidize. Museums housing Clarification maintain carefully controlled humidity and lighting to protect the delicate washes and dot patterns. When exhibited, the painting is often matted with acid-free archival board and framed behind UV-filtering glass to minimize exposure. High-resolution digital reproduction allows scholars to study Klee’s dot placement and pigment layering in detail, while infrared reflectography can reveal preliminary pencil grids hidden beneath the surface. Such technical analysis deepens understanding of Klee’s meticulous process and informs best practices for preserving his legacy.

Conclusion: The Essence of Clarification

Paul Klee’s Clarification (1932) embodies the artist’s conviction that true insight arises from the interplay of structure and nuance. Through a field of rhythmic dots and a subtly articulated grid, punctuated by a singular green crescent, Klee renders visible the invisible processes of perception, cognition, and poetic revelation. The painting stands as a landmark in his career and in the broader evolution of abstraction, demonstrating that minimal visual elements, when orchestrated with sensitivity and intention, can evoke profound emotional and intellectual responses. In Clarification, Klee offers no answers but rather a luminous invitation to engage in the timeless work of making sense of the world.