Image source: wikiart.org

Christ on the Cross: First Impressions of Zurbaran’s Vision

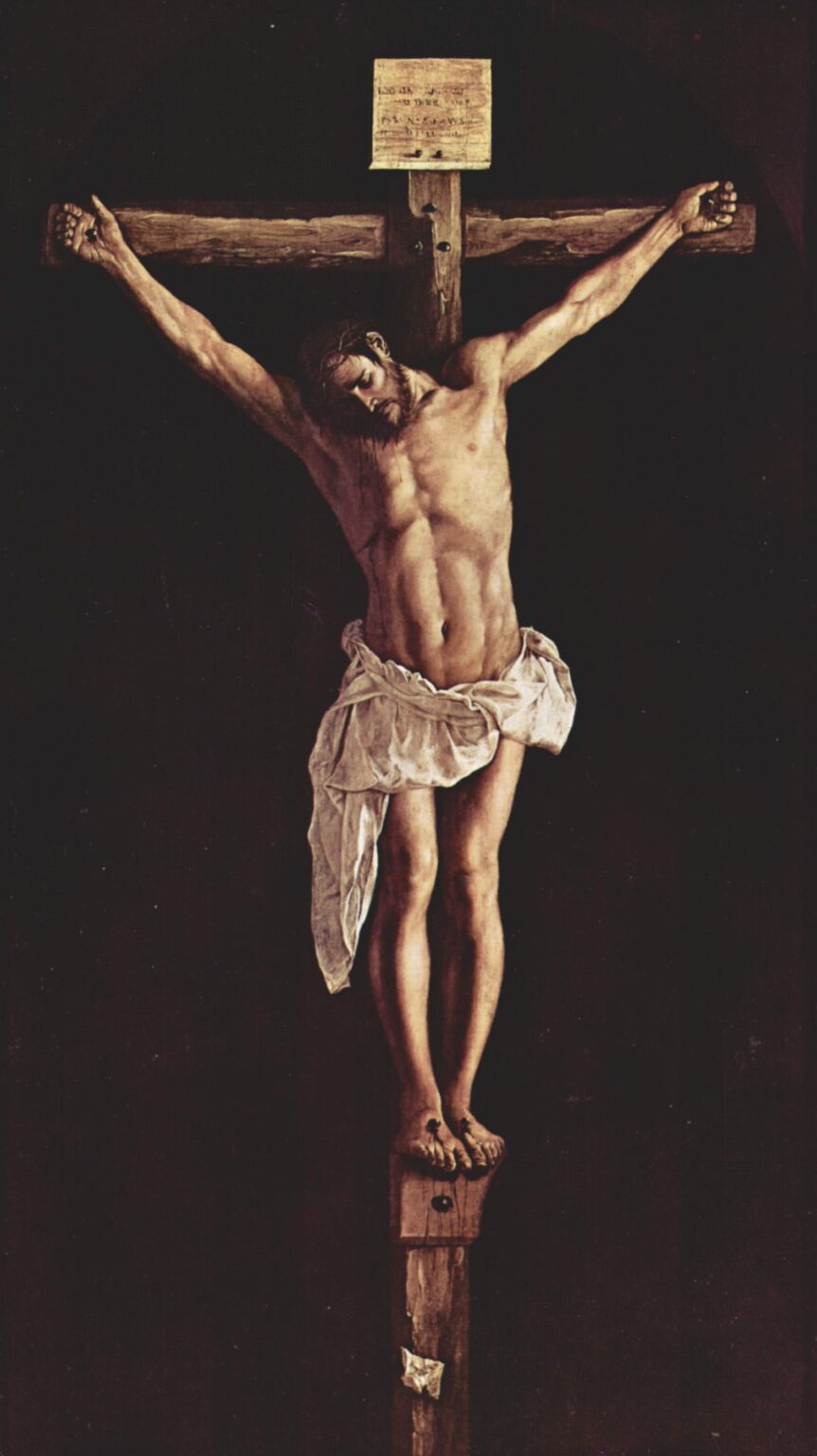

Francisco de Zurbaran’s “Christ on the Cross,” painted in 1627, is one of the most arresting images of the Crucifixion in seventeenth century Spain. At first glance, the viewer is struck by the stark simplicity of the scene. Christ’s body is suspended in an almost impenetrable darkness, illuminated by a hard, focused light that brings every muscle, vein, and fold of cloth into sharp relief. There is no crowd, no landscape, no narrative detail to distract from the solitary figure of the Savior.

The painting presents Christ full length, frontally, nailed to a sturdy wooden cross that emerges from the gloom. His head falls to one side, his eyes closed, the body slightly contorted by the weight that drags it downward. The white loincloth, knotted around his hips, becomes a luminous focal point at the center of the composition. Above his head is the small board bearing the inscription that identifies him as “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews,” and at the base of the cross a scrap of paper appears tacked to the wood.

This restrained, almost minimal staging turns the image into a powerful meditation on suffering and salvation. It feels less like a narrative illustration and more like a vision that has emerged from the dark interior of a chapel or from the inner space of prayer. Zurbaran offers a crucifix that is at once realistic and intensely spiritual, inviting the viewer into a silent encounter with Christ’s sacrifice.

Historical and Religious Context of the Painting

Zurbaran painted “Christ on the Cross” at the height of the Counter Reformation, when the Catholic Church encouraged emotionally direct images that could move believers to deeper devotion. Spain in the early seventeenth century was a deeply religious society in which monasteries, confraternities, and churches commissioned works specifically intended to support contemplation and prayer.

Within this context, the Crucifixion held a central place. Meditations on Christ’s Passion were encouraged in spiritual writings of the period, and believers were invited to imagine themselves at the foot of the cross, participating emotionally in the suffering of Christ. Artists responded by producing images that focused on the physical reality of the body and the psychological intensity of the moment.

Zurbaran, active mainly in Seville, became one of the great interpreters of this religious climate. His ability to combine unflinching realism with mystical stillness made him an ideal painter for monastic patrons. “Christ on the Cross” reflects this environment. Rather than emphasizing the narrative details found in earlier depictions of Calvary, Zurbaran distills the scene to its essential elements in order to support quiet, interior contemplation.

The painting also shows the influence of Caravaggio and his followers, whose dramatic use of light and shadow had spread across Europe. Spanish painters adapted this language of tenebrism to their own religious needs, and Zurbaran’s Crucifix is a perfect example of how the stark contrast between light and darkness can be used to express theological meaning.

A Composition Built Around the Solitary Figure of Christ

The structure of “Christ on the Cross” is based on strong vertical and horizontal lines. The cross forms a monumental “T” that anchors the composition within the tall, narrow format of the canvas. Christ’s body follows the vertical line of the cross but deviates from it slightly through the natural curve created by the weight of the body and the tilt of the head. This subtle deviation makes the figure feel alive and vulnerable rather than rigid.

Zurbaran places Christ’s extended arms along the horizontal bar of the cross, creating a broad span that nearly touches the edges of the picture. This wide gesture emphasizes both the physical strain of crucifixion and the theological notion of Christ’s arms open to embrace humanity. The entire body appears suspended in the center of the painting, surrounded by a deep, featureless darkness that isolates it completely from any environment.

The composition is carefully balanced. The bright loincloth creates a visual center of gravity around Christ’s hips, while the darker torso and legs recede slightly into the surrounding shadow. The small board above the head and the wooden block at the base of the cross act as anchors that keep the viewer’s eye traveling up and down the length of the figure. This vertical movement mirrors the spiritual journey from earthly suffering to heavenly redemption.

By eliminating all other figures and details, Zurbaran turns the composition into a kind of sacred icon. The viewer’s gaze has nowhere else to go; it must confront the presence of the crucified Christ directly and without distraction.

The Dramatic Use of Light and Shadow

One of the most distinctive features of the painting is its dramatic lighting. A strong, directional light falls from the left, scoring the body with highlights and plunging the background into almost complete darkness. The contrast between the illuminated flesh and the void around it is extreme, creating a sense that Christ is emerging from the depths of emptiness.

This tenebrist effect has several consequences. First, it enhances the physicality of the figure. Muscles, ribs, and tendons stand out with sculptural clarity. The light grazes the surface of the skin, revealing the subtle modeling of the torso and limbs. The body appears almost tangible, as if carved from marble yet warmed by living blood.

Second, the darkness functions as a spiritual symbol. In Christian theology, the Crucifixion is associated with cosmic darkness, the moment when the sun is obscured and creation itself mourns. Zurbaran translates this idea visually: Christ is surrounded by a blackness that suggests both the night of Good Friday and the spiritual darkness of sin and death. Against this abyss, his body becomes the one source of light, signifying redemption and divine presence.

Finally, the lighting intensifies the emotional tone. The shadows that fall across Christ’s face partly conceal his expression, creating an air of mystery and interior suffering. We cannot fully read his emotions, which invites the viewer to fill the silence with their own prayers and reflections. The light does not simply describe physical forms; it shapes a profound atmosphere of solemnity and awe.

The Body of Christ: Beauty, Suffering, and Restraint

Zurbaran’s Christ is strikingly physical but not excessively gruesome. The body is idealized to a degree, with well defined muscles and harmonious proportions. Yet it is also marked by the pain of crucifixion. The arms stretch tautly under the strain, the chest expands, and the feet overlap, pierced by a single nail. Small but unmistakable wounds mark the hands and feet, and a suggestion of blood appears near them, yet Zurbaran avoids excessive gore.

This balance between beauty and suffering reflects Counter Reformation aesthetics. The Church encouraged images that would move believers to compassion without repelling them. A too brutal representation could hinder prayer, while a purely idealized figure might minimize the reality of Christ’s sacrifice. Zurbaran finds a middle path: Christ is a noble, almost classical body subjected to genuine torment.

The pose is carefully considered. Christ’s head droops to one side, his chin resting on his chest, suggesting that the moment of death has already come or is very near. The slight twist of the torso and the bend of one leg introduce a sense of movement even in this suspended state. It is as if the last breath has just left the body, leaving behind a shell that still echoes with life.

The face of Christ is treated with particular tenderness. The features are gentle, the lips slightly parted, the eyes closed in an expression of resignation and peace rather than violent agony. The crown of thorns is present but understated, blending into the shadow of the hair. This restraint focuses the viewer less on the physical torment and more on the voluntary acceptance of suffering. Christ appears as a willing sacrifice, not a victim overwhelmed by pain.

The Expressive Loincloth and the Language of Drapery

While the composition is dominated by the figure of Christ, the white loincloth plays an important visual and symbolic role. Zurbaran was renowned for his ability to paint fabrics, and here he turns the simple cloth into an expressive element that mediates between the human body and the surrounding darkness.

The cloth is painted with sharp folds and crisp highlights, catching the light in such a way that it almost glows against the deep background. Its complex arrangement around Christ’s hips suggests a careful knot, with one corner hanging down in front and another twisting to the side. The texture of the fabric is palpable; it appears rough yet soft, a humble material elevated by its association with the sacred body.

Symbolically, the loincloth evokes both modesty and vulnerability. It preserves Christ’s dignity in death, in accordance with devotional sensibilities of the time, yet it also accentuates the near nakedness of the figure. The expanse of exposed flesh becomes even more striking when framed by the stark white cloth. The purity of the color has obvious theological overtones, associated with innocence and holiness.

The drapery also carries a subtle allusion to liturgical garments. In a chapel setting, the bright cloth would echo the white vestments worn during certain feasts, linking the image of the Crucifixion with the ritual of the Mass. In this way, the painting invites the viewer to see the sacrifice on the cross as continually present in the celebration of the Eucharist.

The Cross, the Inscriptions, and the Objects at the Base

Zurbaran treats the wooden cross with as much realism as the body of Christ. The beams are thick and heavy, their grain visible, the edges worn and rough. This tangible materiality underlines the weight of the structure that supports the suspended body. The solidity of the wood contrasts with the fragility of flesh, reinforcing the sense of physical strain.

Above Christ’s head is the small sign with the inscription “INRI,” presented as a weathered board attached to the cross. Zurbaran paints it as a real object with shadows, not as a mere decorative label. The lettering, although not fully legible, suggests the official announcement of Christ’s identity and condemnation. It is a reminder of the historical event of the Crucifixion, even within this otherwise timeless, abstract space.

At the bottom of the cross, another detail appears: a scrap of paper affixed to the wood. This small object has generated various interpretations. Some have seen it as a symbolic receipt of debt, alluding to the idea that Christ’s sacrifice has paid the debt of sin. Others see it as a painterly signature device or as a reference to devotional texts. Whatever the exact meaning, the paper emphasizes the human reality of the scene. It is a modest piece of everyday material placed on the instrument of salvation, a bridge between ordinary life and the sacred event.

By giving such attention to the cross and its attachments, Zurbaran reminds the viewer that the Crucifixion is not only a spiritual mystery but also a concrete, historical execution carried out with recognizable tools and materials.

Color, Texture, and the Atmosphere of Silence

The color palette of “Christ on the Cross” is extremely restricted. The background is a deep, nearly uniform dark tone that absorbs light. The cross is painted in warm browns, and the body of Christ in muted flesh tones. Only the white loincloth introduces a strong chromatic accent. This limited palette serves several purposes.

First, it intensifies the unity of the composition. The viewer is not distracted by variation in color; instead, attention is drawn to the interplay of light and shadow on a few carefully chosen surfaces. Second, the subdued tones contribute to a solemn, meditative atmosphere, appropriate for a work destined for a chapel or monastery.

The textures are rendered with impressive realism. The rough grain of the wood contrasts with the smooth skin of the body and the soft creases of the linen cloth. This contrast heightens the sensory experience of the painting. The viewer can almost feel the splintered surface of the cross and the weight of the cloth.

All of these elements combine to create an atmosphere of profound silence. There is no motion in the background, no suggestion of wind or noise. The stillness is almost palpable. The painting feels like a moment held in suspension outside of time, suitable for prayer and contemplation.

Devotional Function and Spiritual Interpretation

“Christ on the Cross” was not intended as an art object to be admired at a distance; it was created for devotional use, probably in a monastic or church setting where viewers would stand or kneel before it in prayer. The frontal, life size scale of the figure invites a direct, personal engagement.

In such a setting, the painting served as a visual aid to meditation on the Passion. Believers were encouraged to imagine themselves present at Calvary, to contemplate Christ’s wounds, and to respond with gratitude and sorrow. Zurbaran’s emphasis on the physical reality of the body facilitates this kind of empathetic identification. At the same time, the serene expression and luminous light suggest victory over death and the promise of redemption.

The darkness surrounding Christ can be interpreted spiritually as the darkness of sin that is pierced by the light of divine grace. The solitary figure on the cross embodies the belief that Christ suffered alone for the salvation of all. The absence of other figures places the responsibility for response squarely on the viewer. There is no Mary, no St John, no soldiers to model emotion; the viewer must supply their own.

Thus the painting operates on two levels. It is a vivid representation of a physical execution and a theological statement about sacrifice, love, and redemption. The viewer is invited not simply to observe but to enter into a relationship with the crucified Christ, to recognize in his suffering a source of hope and transformation.

Zurbaran’s Style and the Place of This Work in His Oeuvre

Francisco de Zurbaran is often grouped with artists like El Greco, Velazquez, and Murillo as one of the major figures of the Spanish Golden Age. Yet his style has a distinctive character, marked by quiet intensity, strong contrasts of light and dark, and a focus on solitary figures. “Christ on the Cross” exemplifies this personal vision.

Compared with more dynamic Baroque compositions that feature swirling draperies and complex groupings of figures, Zurbaran’s Crucifixion is remarkably austere. The composition is stable, almost geometric. This preference for stability and clarity appears in many of his works, particularly in his paintings of monks, saints, and still lifes. He often portrays his subjects as isolated figures set against dark backgrounds, emphasizing their spiritual interiority.

In “Christ on the Cross,” the same approach yields a monumental image that feels both intimate and monumental. It bears comparison with carved wooden crucifixes used in Spanish churches, which were often painted and displayed for veneration. Zurbaran seems to translate the presence of such sculptures into paint, preserving their frontal, devotional character while adding the subtleties of light and color that only painting can provide.

The work also reveals his skill in rendering different materials, a skill that would later be displayed in his famous still lifes of ceramics, fruits, and simple objects. Here, the flesh, wood, and fabric become vehicles for spiritual meaning, not merely demonstrations of technical ability.

Within Zurbaran’s career, this painting is a key statement about his ability to fuse realism and mysticism. It stands as an early masterpiece that would influence later Spanish religious painting and help define the visual language of devotion in seventeenth century Iberia.

Continuing Power and Modern Reception

Even for contemporary viewers who may not share the intense devotional culture of seventeenth century Spain, “Christ on the Cross” remains a powerful image. Its simplicity gives it a timeless quality. The isolation of the figure against darkness can be read not only in theological terms but also as a broader meditation on suffering, mortality, and the search for meaning.

Modern audiences often respond to the psychological depth of the painting. The silence, the absence of narrative detail, and the concentrated focus on the human body resonate with feelings of solitude and vulnerability that are still very much part of human experience. The painting does not insist on a particular emotion; rather, it opens a space in which viewers can project their own questions and reflections.

At the same time, the work continues to be appreciated for its artistic qualities. The mastery of lighting, the subtle modeling of anatomy, and the balance of the composition place Zurbaran among the great masters of Baroque painting. Museums and art historians often highlight this Crucifixion as an example of how religious art can achieve both doctrinal clarity and profound artistic sophistication.

In church settings, reproductions of this image are still used as aids to prayer, demonstrating its continued relevance in Christian devotion. In secular contexts, it is admired as a moving exploration of the human condition through the language of paint.

Conclusion: A Silent Encounter with the Sacred

“Christ on the Cross” by Francisco de Zurbaran is more than a historical artifact from seventeenth century Spain. It is an enduring visual meditation on sacrifice, suffering, and redemption. Through a carefully constructed composition, dramatic lighting, realistic anatomy, and restrained yet eloquent symbolism, Zurbaran creates an image that invites prolonged contemplation.

The painting’s power lies in its simplicity. By removing the crowd of Calvary and focusing solely on the solitary figure of Christ, Zurbaran compels the viewer to face the Crucifixion directly. The darkness that surrounds the cross, the glow of the body and cloth, and the quiet expression of the crucified Christ combine to create a profound atmosphere of awe and reverence.

Whether approached as a work of faith or as a masterpiece of Baroque art, this painting offers a deeply moving experience. It turns the canvas into a threshold between the visible and the invisible, the historical and the eternal. Standing before this Christ, viewers are invited into a silent encounter that has the potential to touch both the mind and the heart.