Image source: wikiart.org

A Singular Vision of Sacrifice

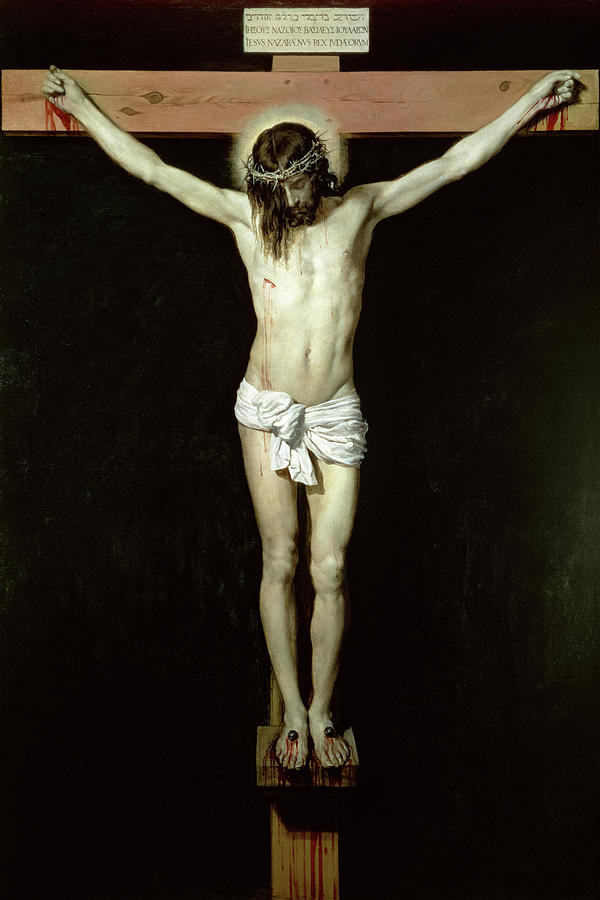

Diego Velazquez’s “Christ on the Cross” (1632) stands among the most concentrated statements of faith and painting in seventeenth-century Spain. Dispensing with attendant figures, landscape, and narrative paraphernalia, the artist isolates the crucified body of Christ against a fathomless black ground. A pale, living anatomized form hovers before the viewer, nailed to a simple timber cross beneath the INRI placard. The head bows slightly forward, a crown of thorns presses into the brow, and a white loincloth gathers in a knot that glows with almost sculptural clarity. The image is not theatrical; it is contemplative. Velazquez transforms the scene of the Passion into a still, solemn apparition designed to be held in the mind, a devotional image of the highest austerity where every choice serves meditation rather than spectacle.

Historical Moment and Counter-Reformation Purpose

The painting belongs to the Spanish Counter-Reformation, when images were commissioned not to ornament doctrine but to aid prayer, to kindle contrition, and to instruct the senses. In 1632, Velazquez had been at the Madrid court for several years, absorbing Italian lessons of atmosphere and tone while remaining deeply conversant with Sevillian tenebrism. Spain’s visual culture favored clarity over embellishment and sincerity over flourish in sacred subjects. “Christ on the Cross” answers those imperatives with a radical paring down of means. The void of the background excludes distractions; the symmetrical structure reins in emotion without denying it; the meticulous observation of the human body invites identification with the suffering it bears. The work thereby fulfills the Counter-Reformation ideal of images that are both intelligible and spiritually efficacious.

Composition, Axis, and the Architecture of Attention

The composition draws its immense power from geometry. The cross is nearly frontal, its horizontal beam forming a firm bar that halts the eye and announces the instrument of execution. Christ’s body, elegantly elongated, becomes the vertical axis around which the entire painting coheres. He is centered in a way that feels inevitable rather than rigid: the slight cant of the head, the gentle asymmetry of the shoulders as the arms stretch outward, and the relaxed bend of the knees save the image from mechanical symmetry. This harmony of near-symmetry and small deviations creates a living equilibrium. The viewer’s sight rises to the INRI inscription and then drops, inevitably, to the face and torso before arriving at the small wooden suppedaneum, stained with the deep red of falling blood. The structure governs attention with liturgical calm.

The Black Ground and the Theological Void

Few choices in Baroque art are as decisive as Velazquez’s black field. It is not merely a background; it is an infinite, unlocatable space that cancels historical contingency. There is no Jerusalem, no crowd, no sky at midday. In theological terms, the void becomes a cosmic stage where the sacrifice is universal and perpetual, outside time yet addressed to each beholder now. The black intensifies the whiteness of the loincloth, the pallor of flesh, and the honeyed timbers of the cross; it also absorbs the brightest lights, allowing halos and highlights to appear with reserved authority. The result is a visual silence in which even small passages—drops of blood, a glint on a nail head, the soft rim of the halo—resonate like clear notes in a chapel after the choir has departed.

Light, Flesh, and the Discipline of Chiaroscuro

Light enters from upper left and models the body with a serenity that belies the violence it records. Velazquez refuses the high drama of spotlight. Instead, he lays a broad, cool illumination that caresses clavicle, ribcage, abdomen, and thigh, permitting every plane to speak. The flesh is rendered with tonal transitions of exquisite restraint: warm half-tones on the chest, cooler shadows under the arms, a pearly sheen on the knees and feet. The blood is not a torrent but a measured testimony. Threads descend from the hands, a darker flow stains the feet and the small block, and a slender rivulet draws a red line from the wound in the side across the torso. The viewer senses not gore but truth. This is chiaroscuro in the service of compassion, where darkness frames suffering and light confers dignity.

The Halo and the Crown of Thorns

Velazquez articulates sanctity with economy. The halo is a muted aureole of light that gathers behind the head, more a thickening of radiance than a drawn circle. It is so modest that one can almost miss it, and that modesty matters. The sanctity here is not an ornamental addition but a natural effulgence of divine personhood under suffering. The crown of thorns, by contrast, is tactile and specific. Its thorn tips bite the brow; strands of hair tangle around the branches; small spots of blood mark the forehead. The dialogue between the quiet halo and the thorny crown—between divine identity and human pain—encapsulates the painting’s theology in visual terms.

Anatomy, Dignity, and the Refusal of Sensationalism

The body is observed with a fidelity that honors both classical ideals and lived corporeality. Muscles are present but not heroic; the abdomen is taut but not exaggerated; the hands, splayed by the nails, are rendered with a calm that forgoes grimace. The head’s tilt, the soft fall of hair, and the closed eyes introduce pathos without theatrics. Velazquez never lingers on distorted agony; instead, he shows a body at the extreme limit of endurance dignified by acceptance. The loincloth’s knot, central and luminous, plays a crucial role: it preserves modesty, forms a visual counterweight to the head, and affirms the material reality of fabric in a scene conceived with sculptural sobriety. The anatomized truth of the figure invites meditative empathy rather than voyeuristic shock.

The INRI Tablet and the Language of Witness

Above the head, the tablet bearing “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” appears in a calm, legible panel. Its presence situates the event within the juridical order that condemned Jesus, and in a practical sense it anchors the top of the composition. Importantly, the tablet is recessed in the light, a pale rectangle that echoes the loincloth below, creating a vertical rhyme of whiteness. Between those two bright registers—the proclamation above and the cloth below—extends the living column of the Savior’s body. The painting thus reads as a sentence: title, embodiment, and testimony of blood.

Silence, Prayer, and the Viewer’s Role

The painting is as much an instrument as it is an object. Made for devotion, it asks the viewer to assume a posture of attention. The empty field becomes a space for private prayer; the centered body offers a focus for affective meditation; the restrained depiction of wounds allows the imagination to move toward contrition without revulsion. Even the downward angle of the head acknowledges the beholder’s presence, as if Christ listens to the prayers said before the image. Velazquez balances doctrinal clarity with spiritual intimacy, producing a work that can be read in a chapel by a single penitent or encountered in a gallery by many, always with the feeling that it looks back gently from the brink of death.

Spanish Baroque Austerity and Italian Air

Velazquez merges the Spanish devotion to austerity with a learned Italian sense of pictorial air. The edges of the limbs soften gently into the surrounding darkness; reflected lights under the arms and across the flank persuade the viewer of real space around the figure; the cross’s grain reads as wood rather than as diagram. These atmospheric cues stem from his studies of Venetian and Roman painting, yet they serve a distinctly Spanish ethic: to let the image be strong through simplicity. The result is a crucifixion that avoids the decorative pluralism of multi-figure Baroque compositions while achieving a grandeur as capacious as any.

Comparisons and Singularities

Contemporaries such as Francisco de Zurbarán and Jusepe de Ribera painted crucifixions with comparable seriousness of tone and an appetite for tenebrist drama. Velazquez’s version separates itself by its synthesis of restraint and presence. Where Zurbarán sometimes freezes forms into sculptural stillness, Velazquez lets air circulate; where Ribera can dwell on the bodily ravages of martyrdom, Velazquez emphasizes the interior assent of the victim. The painting’s unusual frontal address, its absence of landscape, and its finely balanced anatomy yield a devotional icon for meditation rather than a narrative of event. This singularity explains why the work has often been treated as the standard for Spanish crucifixion imagery.

The Color of Redemption

The chromatic scale is narrow but eloquent. Blanching flesh, white textile, honeyed wood, and deep black provide a liturgical palette in which red serves as the sacramental accent. Blood marks are small yet saturated, drawing the eye to the anatomical points of significance—the hands, feet, side, and the vertical run along the suppedaneum. The color design acts like a creed in pigment: incarnation in flesh tones, purity and burial shroud in white, instrument of death in wood, death’s abyss in black, and atonement in red. Each hue carries devotionally charged meaning without the need for overt symbolism.

The Rhythm of Lines and the Mercy of Curves

Though the cross is made of right angles, the body describes arcs. The arms stretch outward in a soft bow, the ribcage rounds, the hips shift in a gentle contrapposto, and the legs cross subtly at the ankles. These curves soften the hard geometry and humanize the device of execution. They also create an internal rhythm: horizontal beam, curved arms, vertical torso, curved thighs, and squared platform. The alternation of angle and curve mirrors the alternation of justice and mercy central to the Passion narrative, generating a subliminal harmony that steadies emotion.

Paint, Varnish, and the Object’s Quiet Surface

Velazquez’s surface is controlled, with thin, even layers building toward a finish that reads as skin rather than enamel. The highlights are small and accurately placed—the nail heads gleam; the edge of the loincloth catches light; the halo hums rather than shines. The grain of the wood is handled with soft dragging strokes that suggest fiber without pedantry. The painting’s quiet skin contributes to its devotional efficacy: nothing distracts, nothing calls attention to virtuosity, yet everything is true enough to sustain prolonged looking.

Suffering, Acceptance, and the Theology of the Head

The bowed head anchors the painting’s pathos. It is the spiritual center where humanity’s sorrow and divine obedience meet. The closed eyes exclude the world’s accusations; the mouth is relaxed, neither crying out nor grimly clenched. This is not a narrative instant of shouting or eclipse; it is a timeless image of acceptance approached by silence. The head’s position also guides the viewer’s own gesture; the painting seems to encourage an answering inclination, as if the beholder’s prayer were a mirror of Christ’s submission.

Devotional Use and Modern Resonance

Although conceived for sacred space, the image speaks across confessional and historical lines because of the sobriety of its language. It does not depend on the scaffolding of a particular story or patron; it offers the universal terms of body, light, and silence. Modern viewers often praise the painting for its minimalism avant la lettre—the way it reduces means to amplify meaning—while believers continue to find in it a reliable instrument of prayer. Its authority resides in its refusal of coercion: the painting persuades rather than overwhelms.

Legacy and Influence

“Christ on the Cross” helped define a Spanish mode of sacred painting in which austerity became eloquence. Later artists in Spain and beyond would adopt the solitary crucified figure against a void, the measured blood, the quiet halo, and the frontal address. Yet the work remains difficult to imitate because its success depends on balances that are easy to name and hard to achieve: fullness without clutter, anatomy without bravura, pathos without sentimentalism, and theology without emblem overload. It is a summa of Velazquez’s early maturity, where all the lessons of Seville, Madrid, and Italy converge in a single, clarifying vision.

Conclusion: The Still Point of the Passion

At the heart of Velazquez’s painting is a paradox: an execution presented as stillness, a death that reads as life offered, a darkness that clears the way for light. By paring away everything but the essential, the artist allows the crucified body to become a still point in a turning world. The cross stands, the head bows, the blood falls, and the viewer enters a space of regard where grief, gratitude, and hope can cohere. Few paintings sustain such concentrated attention with such gentle means. “Christ on the Cross” remains what it has always been: an image to steady the mind and school the heart, a luminous presence in the midst of night.