Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

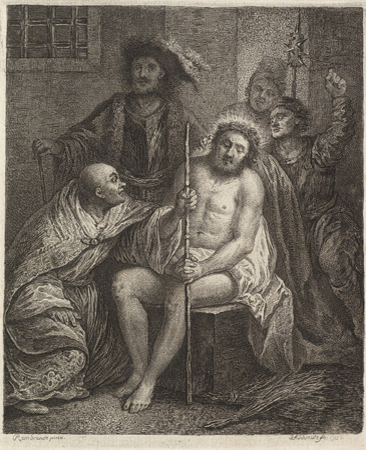

Rembrandt’s “Christ Crowned with Thorns” presents one of the Passion’s most psychologically charged moments with a mixture of theatrical immediacy and compassionate restraint. Christ, nude to the waist and seated on a rough block, leans forward beneath a crown of woven thorns while soldiers and officials mock him as “King.” A reed stands in for a scepter; a rag substitutes for royal robe; a torch flares and a fist lifts in the background; a window grates the upper left like a mute chorus of bars. Rather than staging cruelty as spectacle, Rembrandt turns the scene into an intimate drama of faces, hands, and light, where the true subject is not violence itself but how human beings choose to face it. The image is technically a print—an etching enriched, as so many of his works are, with drypoint and subtle burr—yet its tonal depth and painterly tact convey the fullness of a painted nocturne. It is a work that asks viewers to attend to small gestures and to find in those gestures the weight of the story.

Medium And The Power Of The Print

Understanding the medium clarifies why this image feels so alive. Etching allows the artist to draw freely through a protective ground into copper; acid then bites those lines to hold ink. Rembrandt used the process not simply to reproduce an idea but to create the idea in the copper itself. The varied widths of his lines register changes of pressure and speed; drypoint additions throw up soft ridges of metal that print as velvet shadows; selective wiping leaves films of tone that behave like atmosphere. In “Christ Crowned with Thorns,” he plays these resources like an instrument. Crisp, sure lines define the tilted reed, the edge of a robe, the contour of a hand. Feathery burred strokes soften Christ’s halo and the gloom beyond the torch, creating a palpable air in which bodies breathe. Because the plate can be reworked between impressions, the print likely existed in multiple “states,” each refining the scene’s light. This malleability suits the subject, for the Passion narratives themselves unfold as a sequence of recognitions.

Composition As Staged Encounter

The composition compresses five figures around Christ, generating both pressure and focus. He sits low and slightly right of center, angled toward a kneeling official who points and pleads with an upturned hand. Behind, a crowned officer looms; to the right, a soldier with a staff shouts while another raises a fist. The left half of the plate is dominated by the kneeling figure’s heavy drapery and the stone wall with its barred window; the right half is alive with torchlight and movement. These halves meet at Christ’s body, whose curve becomes the pivot of the drama. The tilt of his head, the inward bend of his torso, and the reed’s slender vertical create a lyric triangle against the crowd’s diagonals. Nothing feels static. The eye is ushered by gesture—from the kneeler’s hand to the reed, from the reed to the wound-shadowed ribs, from those ribs to the face whose patience steadies the entire stage.

Chiaroscuro As Moral Speech

Light in this print is not merely descriptive; it is ethical. A cool, steady illumination bathes Christ’s chest and face, rendering flesh with tenderness despite the harshness of the moment. The surrounding figures are lit more fitfully: a gleam rides the kneeler’s bald pate, the torch throws selective highlights on the shouting soldier, the back figure dissolves into half-visibility. This unequal distribution proposes a hierarchy of attention. The center of regard belongs to the suffering one; those who mock him are allowed legibility but not glory. The light’s logic thus contradicts the mock coronation’s logic. Where the crowd tries to install a parody king, the print quietly enthrones the true protagonist by seeing him most clearly.

The Halo And The Reed

Two slender motifs narrate the paradox of kingship: the halo and the reed. The halo is not a hard disc but a trembling haze of radiance that shares tone with the torch’s glow yet remains separate in quality. It is less a badge than a presence, a luminescence that issues from the figure rather than being imposed on it. The reed, by contrast, is a literal prop and an instrument of mockery. Rembrandt draws it with wiry exactness, even letting it project beyond Christ’s lap toward the kneeler’s hand. The eye follows its shaft as if it were an arrow of irony pointing from royal pretense to true royalty. Together these signs enact the whole scene’s inversion: the instruments of humiliation turn into instruments of revelation.

Hands And The Grammar Of Emotion

As often in Rembrandt’s work, hands do the talking. The kneeling official’s left hand opens like a rhetorical fan, while his right clutches at Christ’s reed-scepter with a mixture of persuasion and manipulation. The soldier’s fist at far right is a knot of violence. Christ’s own hands are restrained: one rests in his lap, the other lightly holds the reed, fingers neither grasping nor relinquishing. This quiet touch is decisive. It refuses the crowd’s logic without theatrical defiance. The hand seems to say, “I will not fight you on your terms.” The result is a grammar of emotion richer than any facial caricature: arrogance, agitation, wheedling, cruelty, mercy—each readable in the posture of the fingers.

Faces And Psychological Nuance

The faces are portraits of different economies of attention. The kneeler’s profile, etched with care, advertises worldly intelligence and a habit of calculation; his eyes are sharp, his mouth active. The soldier who shouts has his features abbreviated, as if voice mattered more than visage; he is rendered as noise turned flesh. The man behind the torch peeks past the flame with a voyeur’s curiosity, half-hidden and lit from below, becoming a figure of ambiguous complicity. The crowned officer at the back stands aloof, the decorative brim and plume of his hat catching light while his features remain generalized. Then there is Christ: brow knit with pain but not contorted, gaze lowered and inward, mouth opened slightly as if in breath or prayer. The range compresses human possibility into a single, legible scene without reducing anyone to a cipher.

Space, Architecture, And The Poetics Of Confinement

The setting is economical yet precise. A barred window occupies the upper left, its regular grid standing in cold contrast to the organic tumult below. The coarse block of Christ’s seat registers as both stone and throne, a cruel material pun. The wall behind forms a shallow stage, preventing escape and forcing each figure to press forward into our space. The confinement is psychological as well as architectural; the print does not allow viewers to stand apart. We are the crowd’s audience and also, uncomfortably, its accomplices. Rembrandt’s shallow stage makes judgment a near event rather than a distant story.

Costume, Texture, And Hierarchy

Textiles carry status, and Rembrandt uses them to articulate power’s hollowness. The kneeling figure’s robe, densely cross-hatched, glitters with bureaucratic prestige; his sleeve falls in impressive cascades. The standing officer’s feathered hat and chain catch sparks of light that say wealth without saying character. The soldiers’ garments are lumpier, their coarse textures sketched with impatient strokes. Christ’s drapery, by contrast, is minimal, and it is the flesh rather than the cloth that receives the richest modeling. Thus the print assigns value contrary to the world’s usual assignments: expensive fabrics are quickly indicated; naked suffering is richly seen.

The Crowning As Inverted Coronation

The subject’s irony—the parody of coronation—has tempted many artists into melodrama. Rembrandt refuses spectacle. He does not show the moment of the crown being rammed down; he shows the longer, quieter humiliation of display and taunt. The aggressors’ gestures are varied but never flamboyant; the violence is certain, but what fills the air is not bloodlust so much as a bristling of attitudes: contempt, curiosity, performative zeal. This choice heightens the scene’s moral sting. It asks viewers to consider not only cruelty but also the small social energies that sustain cruelty—the smirk, the shrug, the clever speech, the comfortable supervision from just behind.

Theological Reading Without Polemic

A devotional reading emerges naturally without dogma. The halo indicates sanctity, the lowered gaze suggests voluntary suffering, the reed and crown transform mockery into sign. But the print does not preach. It trusts the evocation of character to convey meaning: Christ’s patience and interiority, contrasted with the crowd’s busyness, become the doctrine. The image thereby welcomes viewers of varied commitments; its insight into human behavior is exact enough to stand even without explicit theology.

Comparison With Related Works

Rembrandt returned to the Passion repeatedly, from early history paintings to later etchings like the “Hundred Guilder Print” and the “Three Crosses.” “Christ Crowned with Thorns” sits in productive conversation with those works. Like the “Three Crosses,” it uses concentrated light to stage moral clarity; like the “Hundred Guilder Print,” it employs a frieze of varied witnesses to dramatize response as much as event. In comparison to Italian precedent—where Roman uniforms, classical settings, and ideal anatomy dominate—Rembrandt’s version feels nearer to the street, nearer to our scale. A Dutch viewer seeing this print in a modest room could feel that he or she had stumbled upon the scene rather than visited it in a gallery of grand history.

The Plate As Living Object

Rembrandt’s plates rarely sat still. He often scraped, rebit, and burnished to adjust emphasis. In an image like this, he could deepen the shadow under Christ’s arm to give the torso more roundness, strengthen the burr around the torch to enrich the glow, or open the kneeler’s drapery with highlights to avoid visual heaviness. Such adjustments are not ancillary; they are the work’s heartbeat. The state-to-state evolution parallels the narrative’s own unfolding—from arrest to abuse to crucifixion to silence—and allows the maker to respond to his subject with living attention.

Viewer Choreography And The Path Of Looking

The print engineers a guided journey for the eye. Most viewers begin with the brightest flesh—Christ’s torso—then track to the face. From there, the reed pulls the gaze to the kneeling figure’s argumentive hand; the hand sends it back to Christ, whose lowered look deflects us into the right-hand group, where we encounter the torch flare and the raised fist. That circuit returns along the crown’s line to the top of Christ’s head and then down again to the seated block. This loop repeats the scene’s essential movement: humiliation presented, violence threatened, mercy maintained.

Humanism At The Edge Of Violence

A defining feature of Rembrandt’s art is its humanism—the insistence that even at the story’s darkest points, people remain readable and therefore responsible. No one here is faceless. The soldier who shouts still has a mouth that could be silent; the official who argues still has a hand that could refrain from pointing. By giving each agent specificity, the artist refuses to dissolve tragedy into grand forces. Responsibility resides in gestures, and gestures are ours to choose.

The Reed As Line Of Conscience

Beyond narrative function, the reed plays a compositional and philosophical role. It is a straight line in a swarm of curves—an axis of thought amid the flux of passion. Christ holds it lightly, as if demonstrating mastery over the very symbol meant to mock him. To read the print is to read along that reed and ask what steadiness might look like when everything else shouts. The answer emerges not as slogan but as posture: patient, inward, alert, unbroken.

Sound, Silence, And The Print’s Acoustics

Though silent, the image suggests a rich acoustic world. The torch sputters; the soldier shouts; the kneeler murmurs; iron rings clink against the staff. Against this noise, Christ’s silence has the weight of a counter-sound. Rembrandt conjures that silence with the smoothness of modeling across the chest and the downturn of the mouth—visual equivalents of held breath. In a medium that can only show, he manages to make us hear.

How To Look, Slowly

The print rewards slow, neighborly attention. Stand near enough to let the etched lines separate; notice the feathering burr around the torch and the whispering hatches in the shadowed wall. Step back until tone merges and the scene breathes. Shift left and right to see how the white of the paper gleams differently along the halo’s edge, then let your gaze return to the small triangle formed by Christ’s mouth, the reed’s top, and the kneeling hand. That triangle holds the picture’s truth: mock authority, true authority, and the human will suspended between them.

Legacy And Continuing Relevance

The image endures because it clarifies a perennial dilemma: how to remain centered when the surrounding world uses pageantry and noise to humiliate what is gentle. Its formal choices—compressed space, measured light, eloquent hands—serve that inquiry precisely. For printmakers, it remains a lesson in how to make copper feel like air and flesh; for viewers, it is a mirror held up to social life, where derision often masquerades as celebration. The work’s moral, if one exists, is modest but demanding: honor what deserves light, refuse to amplify cruelty, and let your own hands speak mercy.

Conclusion

“Christ Crowned with Thorns” transforms a scene of abuse into a study of conscience. The etching’s lines and tones carry more than description; they carry respect, and that respect becomes the ground on which the subject stands. The halo glows without glare, the reed straightens amid mockery, the hands argue, threaten, or bless, and the light refuses to flatter power. Rembrandt’s genius lies in how these parts assemble into a picture that feels both ancient and immediate. We do not witness a distant spectacle; we share a room with a suffering person and must decide what our own hands will do.