Image source: artvee.com

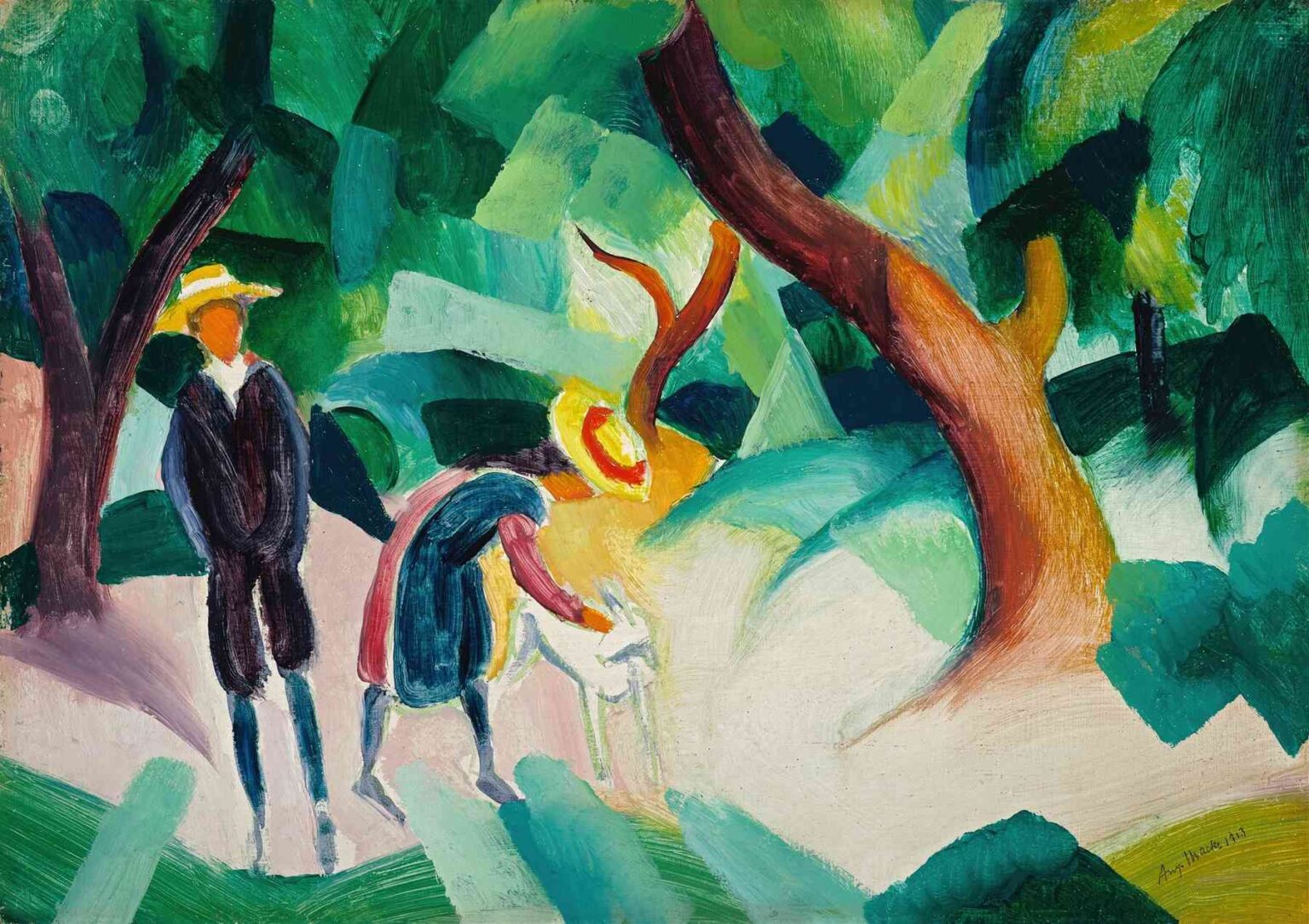

August Macke’s Children with a Goat, painted in 1913, is a vivid and expressive work that encapsulates the harmony of human figures with nature through the lens of early German Expressionism. In this painting, Macke explores themes of innocence, play, and abstraction, offering a window into a peaceful pastoral moment just before the world plunged into the chaos of World War I. Executed with bold, fragmented brushstrokes and a palette of luminous greens, blues, and earthy tones, this work exemplifies Macke’s unique fusion of Fauvist color, Cubist form, and a personal vision rooted in poetic simplicity.

This in-depth analysis explores the historical context, stylistic innovations, thematic depth, and emotional resonance of Children with a Goat, and positions the painting as a vital example of August Macke’s contribution to modern art.

August Macke and the Spirit of 1913

To fully appreciate Children with a Goat, one must understand the artistic and social atmosphere of Europe in 1913. This was a year of unprecedented artistic experimentation. Across the continent, painters were responding to the fragmentation of modern life with equally fragmented visual languages. August Macke (1887–1914), a key figure in the German Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter, stood at the crossroads of several avant-garde movements—Expressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism among them.

Macke’s work in 1913 marks a peak in his artistic development. Having traveled to Paris and Tunisia, and collaborating with artists such as Franz Marc and Robert Delaunay, he was fully immersed in the aesthetic revolution that defined early 20th-century modernism. Children with a Goat was painted during this time of creativity and synthesis, when Macke sought to capture the joyful harmony between humans and their environment using a language of abstracted color and form.

Composition and Visual Structure

The composition of Children with a Goat is deceptively simple yet masterfully orchestrated. The scene shows two children—one standing and one bending toward a white goat—set against a backdrop of stylized trees and foliage. The child at the center interacts with the goat, drawing the viewer’s attention to this moment of tenderness and curiosity. The other child, standing with hands in pockets and head turned slightly, provides compositional balance and emotional contrast.

The canvas is dominated by swirling, faceted shapes in various shades of green, teal, and blue. These angular brushstrokes break the scene into fragments, echoing Cubist influences, but they do not fracture its emotional coherence. Rather, they lend a musical rhythm to the painting, creating a visual symphony of movement and harmony.

The curving tree trunks, painted in warm reds and browns, counteract the cool hues of the foliage and serve as structural anchors within the composition. They help guide the eye from the top of the canvas toward the interaction between the child and the goat. There is a subtle spiral of movement in the layout, suggesting the natural flow of life and time.

Use of Color: Harmony and Expression

Color is central to Macke’s artistic vision, and in Children with a Goat, he deploys it with both emotional sensitivity and structural intelligence. The palette consists mainly of cool greens and blues, evoking a peaceful woodland setting, but it is punctuated by vibrant contrasts. The straw hats of the children are painted in luminous yellows with red bands, and the goat, a symbol of innocence, appears nearly white—glowing against the lush background.

Macke’s use of color was influenced by his exposure to Fauvism and Orphism, particularly the work of Delaunay. Unlike the dark, moody tones of other German Expressionists, Macke favored clarity, light, and balance. The colors in this painting are not realistic in a traditional sense, but they convey the emotional reality of the scene. They speak of a world where children and animals coexist peacefully with nature, untouched by industrialization or political unrest.

Rather than modeling form through light and shadow, Macke creates depth through overlapping color planes. This flattening of space, combined with the brightness of his palette, gives the painting a timeless, almost dreamlike quality.

Themes of Innocence, Nature, and Unity

At its core, Children with a Goat is a meditation on innocence and the unity of life. The interaction between the child and the goat represents a gentle, trusting relationship between humanity and the animal world. The children are depicted without distinct facial features, a common trait in Macke’s work that universalizes them. They are not portraits but archetypes—symbols of purity and wonder.

The setting—a stylized forest glade—further amplifies this sense of harmony. There is no horizon line, no vanishing point, and no intrusion of modern life. The forest seems to envelop the figures in a protective embrace, suggesting a lost Eden or an idyllic retreat from the chaos of urbanization. This idyllic vision was especially poignant in 1913, as Europe stood unknowingly on the brink of war.

Macke’s painting can also be read as an attempt to preserve a fleeting moment. The child reaching toward the goat is caught in an act of discovery, while the other child, more reserved, stands as a quiet observer. These emotional positions—curiosity and contemplation—capture the dual aspects of childhood. The goat, calm and docile, symbolizes a connection to the natural rhythms of life.

Abstraction and the Breakdown of Realism

One of the most striking features of Children with a Goat is its abstraction. While the subject matter is recognizably figurative, the forms are radically simplified and stylized. Macke is not interested in replicating the visual world but in expressing its emotional and spiritual essence. He breaks with traditional perspective and anatomy to emphasize color relationships and rhythmic harmony.

This move toward abstraction aligns Macke with the broader goals of the Der Blaue Reiter group, which sought to create a spiritualized art that transcended material reality. Unlike the Cubists, who dissected form analytically, Macke approached abstraction with lyrical fluidity. His fragmented brushstrokes suggest not mechanical dissection, but the organic fragmentation of sunlight through leaves or the dappled patterns of memory.

The painting is both modern and timeless—rooted in the innovations of its day yet conveying a universal message of peace and connection.

Emotional Tone and Viewer Experience

There is a quiet optimism that pervades Children with a Goat. The scene is free from tension or irony. Instead, it invites the viewer into a moment of serenity and reflection. The absence of facial features paradoxically increases the emotional accessibility of the painting, allowing viewers to project their own memories and feelings onto the scene.

This emotional openness is enhanced by the composition’s fluidity and the vibrant, non-threatening colors. Unlike much of Expressionism, which often leans into psychological angst, Macke’s version of Expressionism seeks harmony. It is expressive not of inner turmoil, but of inner calm.

For modern viewers, Children with a Goat offers a moment of pause—a gentle reminder of the beauty of simplicity, the joy of childhood, and the quiet intelligence of nature. It speaks across time to our longing for connection in a fragmented world.

Macke’s Artistic Legacy and the Tragic Arc

Children with a Goat stands among the last works August Macke completed before his untimely death in World War I in 1914. At just 27, Macke had already achieved remarkable artistic maturity and innovation. His death cut short a career that might have gone on to redefine modern German painting.

This painting, then, is both a celebration and a farewell. It captures a moment of peace just before the storm—a luminous distillation of Macke’s vision of art as a means of creating harmony between humans and their world. In this way, it joins the canon of early 20th-century artworks that document not only a style but a civilization on the brink of transformation.

Conclusion: A Modern Eden in Paint

Children with a Goat by August Macke is more than a charming image of pastoral innocence. It is a deeply thoughtful work that unites abstraction with emotion, color with meaning, and childhood with timeless wisdom. Through simplified forms and a brilliant, expressive palette, Macke communicates a sense of unity and joy that transcends the literal subject matter.

In an age of anxiety, fragmentation, and historical upheaval, this painting remains a beacon of harmony. It invites us to slow down, to look closely, and to remember the quiet wisdom of nature and childhood. Whether viewed through the lens of art history, color theory, or emotional resonance, Children with a Goat remains one of August Macke’s most enduring and accessible masterpieces.