Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

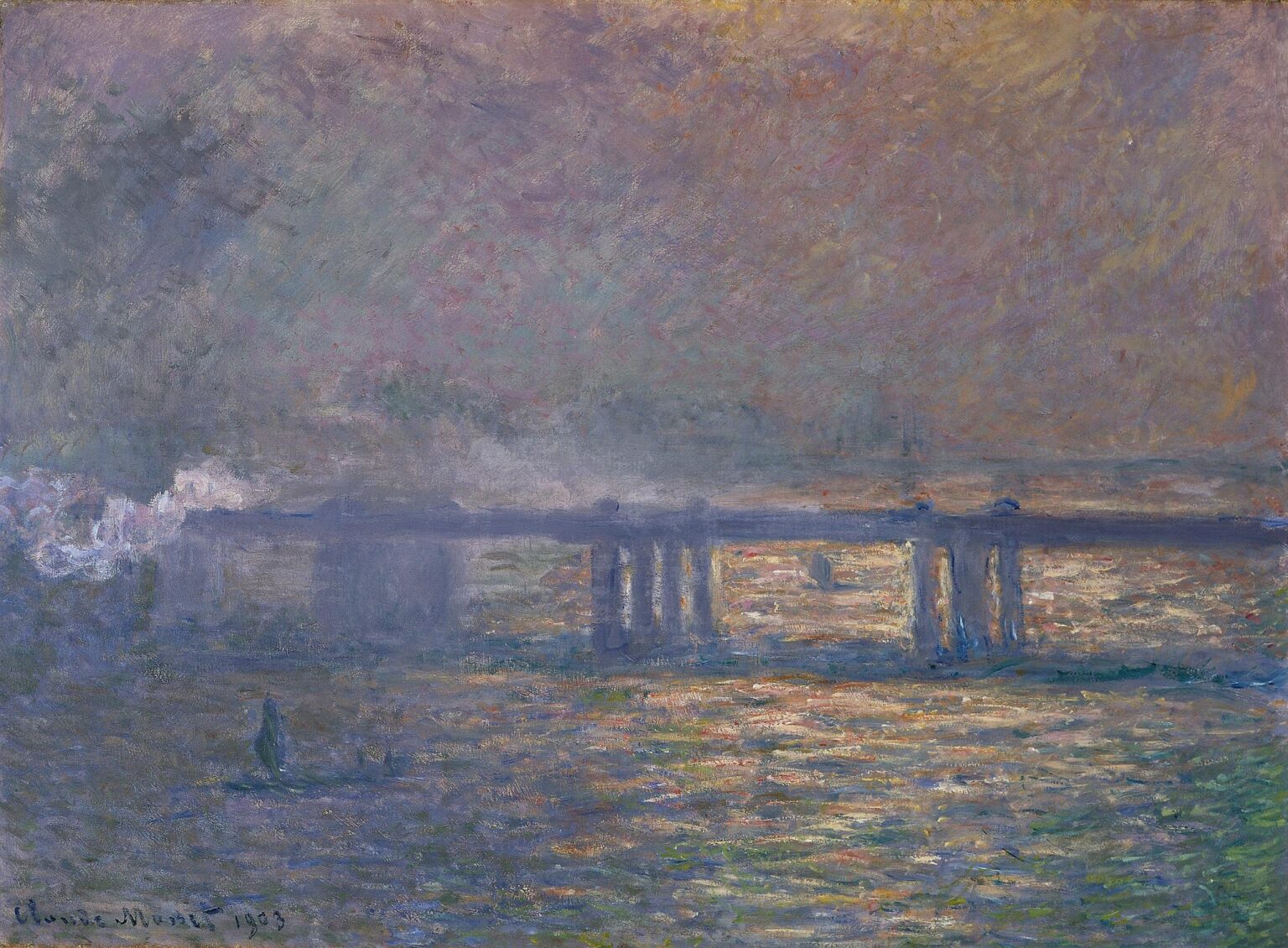

In Charing Cross Bridge (1903), Claude Monet presents a captivating view of London shrouded in the soft veils of dawn mist. Far from a detailed architectural study, this canvas captures the ephemeral interplay of light, color, and atmosphere that characterizes the city’s Thames embankment and the bridge rising like a silhouette through the haze. Monet’s subtle harmonies of lavender, rose, and muted gold evoke the quiet majesty of early morning, transforming a familiar landmark into a poetic vision of urban reverie. Through this painting, Monet demonstrates his enduring fascination with the mutable effects of weather and time, extending Impressionist principles to one of Europe’s great metropolises.

Historical Context

By 1903, London had become a recurring motif for Monet. His first visit in 1899 coincided with a period of profound personal and artistic transition: the closure of his London series marked a new phase in his career, one in which he sought fresh inspiration beyond the banks of the Seine. Britain’s capital, with its iconic river, bridges, and fog-laden light, offered Monet an environment rich in atmospheric phenomena. The Industrial Revolution had endowed London with a distinctive urban haze—coalsmoke mingled with river mist—that diffused sunlight in unpredictable ways. Monet embraced these conditions as opportunities to explore the limits of color and perception, recording scenes that resonate with both realism and abstraction.

Monet’s London Series

Monet’s London works span from 1899 through 1905, encompassing views of Waterloo Bridge, Westminster Bridge, and Charing Cross Bridge in various light and weather conditions. His approach remained consistent: painting en plein air on long stretched canvases, he sought to capture sequential impressions of the same motif under changing atmospheric circumstances. Charing Cross Bridge belongs to the latter half of this series, distinguished by its more introspective mood and muted palette. By focusing on a later hour—dawn rather than the high sun—Monet deepened his exploration of soft light and color transitions, yielding works that verge on the abstract.

Composition and Perspective

Monet organizes Charing Cross Bridge around a horizontal axis defined by the bridge’s graceful arches and the river’s mirrored surface. The composition divides into three primary zones: the expansive sky above, the solid yet misty form of the bridge in the middle ground, and the Thames below, rippling with reflected light. A lone figure in the lower left corner provides scale and a quiet human presence, while distant boats and river traffic dissolve into the haze near the horizon. Monet’s vantage point appears to be the riverbank slightly downstream, allowing an oblique view that emphasizes the bridge’s length and its integration into the cityscape. This measured composition anchors the painting’s atmospheric effects without sacrificing structural coherence.

Treatment of Light and Atmosphere

Light in Charing Cross Bridge is diffused rather than direct, filtered through layers of early-morning fog. Monet employs a high-key treatment: pale pinks and lavenders in the sky transition into silvery grays at the bridge’s apex. Sunlight glimmers on the water in broken touches of gold and rose, illuminating the river’s surface like scattered jewels. Rather than modeling form through chiaroscuro, Monet uses tonal gradations—soft shifts in hue and value—to evoke depth. The bridge’s silhouette emerges from the mist as a series of softened arches, its details suggested through minimal strokes. This emphasis on atmosphere over detail embodies the Impressionist fascination with the transient qualities of light.

Color Palette and Optical Mixing

Monet’s palette in this work is notably restrained, dominated by pastels and subtle contrasts. The sky is rendered in diluted washes of rose madder, cobalt blue, and lead white, while the bridge’s structure depends on mixtures of Payne’s gray and warm off-white. The river reflects the sky’s pinkish tones, interspersed with delicate dashes of clear yellow ochre to suggest sunlight on water. Monet’s technique of placing complementary colors side by side—tiny strokes of purple amid yellow—allows the viewer’s eye to mix them optically, generating a vibrancy that transcends the painting’s subdued chromatic register. This refined color strategy captures the impression of dawn’s fleeting glow more effectively than any literal palette could.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Monet’s brushwork here is both fluid and deliberately varied. In the sky, he applies broad, horizontal strokes that blend seamlessly, conveying the mist’s soft density. By contrast, the water’s surface is built up with shorter, vertical and diagonal touches, evoking ripples and reflections. The bridge’s arches are outlined with slightly firmer yet still loose marks, allowing form to coalesce without hard edges. Occasional impasto highlights—thicker dabs of paint—catch the light of the gallery, mirroring the subject’s luminosity. This interplay between smooth and textured brushwork creates a living surface that engages the viewer’s senses, recalling the physical experience of standing amid fog-shrouded morning air.

Depiction of River and Reflections

The Thames in Charing Cross Bridge functions as a dynamic mirror, reflecting the sky’s hues and the bridge’s faint silhouette. Monet captures the water’s gently undulating surface through a rhythmic pattern of paler and darker strokes. Near the horizon, reflections fade into haze, suggesting depth and distance. Closer to the foreground, light becomes more palpable, with flecks of gold and rose dancing atop the ripples. Monet’s refusal to delineate every vessel or shadow on the river enhances the painting’s atmospheric unity: the water appears less as a discrete plane and more as an extension of sky, a fluid continuum bridging earth and heaven in soft pastel unity.

Symbolism of Fog and Industrialization

London’s characteristic fog—often laced with soot from industrial chimneys—became a hallmark of Monet’s London series. In Charing Cross Bridge, the mist symbolizes both concealment and revelation: it obscures architectural details even as it highlights the play of light. The bridge itself, an emblem of Victorian engineering, emerges as a silent participant in nature’s drama. Its softened form suggests a truce between human ambition and the elemental forces of weather. Monet’s treatment of industrial motifs—bridges, barges, lamplights—within natural phenomena underscores the Impressionist aim to reconcile modernity and the environment, capturing the spirit of an age in which industry and nature coexisted in uneasy harmony.

Emotional Ambience and Mood

Charing Cross Bridge exudes a contemplative mood, inviting reflection rather than spectacle. The subdued palette and enveloping fog evoke a sense of calm introspection suited to early hours. The solitary figure on the bank suggests human solitude in the midst of a vast, indifferent landscape. Monet’s deliberate understatement—eschewing dramatic contrasts or vivid coloration—amplifies the painting’s emotional resonance. Viewers sense a quiet melancholy tempered by the promise of dawn’s new light. In this way, the canvas transcends its urban subject to become a universal meditation on impermanence and renewal.

Place in Monet’s Oeuvre

Among Monet’s London canvases, Charing Cross Bridge occupies a position of serene maturity. Earlier works in the series—such as the more atmospheric Waterloo Bridge studies—often featured denser fog and busier compositions. By 1903, Monet’s approach had distilled to essentials: mood, color, and broad form. This painting anticipates his later water lily panels in Giverny, where he would abandon recognizable landmarks altogether in favor of abstracted fields of light and color. Charing Cross Bridge thus stands at a critical juncture, bridging representational Impressionism and the threshold of modern abstraction.

Technical Studies and Conservation

Scientific examination of Charing Cross Bridge has revealed Monet’s multilayered process. Infrared reflectography uncovers faint underdrawings mapping the bridge’s arches and shoreline, indicating an initial compositional plan. Pigment analysis identifies lead white, ultramarine blue, and madder lake among the primary hues, applied in successive thin glazes. Cross-sectional sampling shows that Monet layered warm underpainting beneath cooler overtones in the sky to achieve luminous depth. Recent conservation efforts have stabilized minor paint losses in the upper left corner and removed varnish discoloration, restoring the painting’s original subtle tonality and preserving Monet’s delicate brushwork for future generations.

Reception and Exhibition History

When first exhibited in Paris in 1904, Charing Cross Bridge prompted admiration for its ethereal quality and nuanced color harmonies. Critics privileged Monet’s ability to transform an industrial landmark into a poetic symbol of light’s transience. The painting soon entered a distinguished private collection before finding its way into a major museum, where it has become emblematic of Monet’s London period. Subsequent retrospectives have highlighted its role in prefiguring modernist explorations of abstraction, inviting scholars to trace lines from Impressionism to early 20th-century avant-garde movements.

Influence and Legacy

Monet’s London works, crowned by Charing Cross Bridge, influenced a generation of artists who sought to reconcile urban subject matter with Impressionist techniques. Post-Impressionists such as Pissarro and Signac admired Monet’s ability to capture cityscapes without sacrificing atmospheric subtlety. In the 20th century, abstractionists like Rothko and Rauschenberg—especially in their hazy, luminous works—drew inspiration from Monet’s focus on color fields and the dissolution of form. Today, Charing Cross Bridge continues to inspire photographers, filmmakers, and painters who explore the visual poetry of urban mist and architectural silhouettes against shifting light.

Cultural Significance

Charing Cross Bridge resonates beyond art history as a visual document of London’s identity at the turn of the century. The painting preserves the era’s characteristic fog and the Thames’s central role in urban life. For contemporary viewers, it offers both a historical snapshot and a timeless meditation on the interplay of nature and industry. The bridge itself, still in use today, stands as a testament to Victorian engineering, while Monet’s impression captures its evocative power under the soft veil of dawn. In an age of digital reproduction, the painting reminds us of the irreplaceable quality of painted surface and the human touch in recording fleeting moments.

Conclusion

In Charing Cross Bridge, Claude Monet distills the essence of London’s riverside dawn into a luminous fusion of color, light, and atmosphere. His deft handling of pastel hues, subtle tonal shifts, and fluid brushwork transforms an architectural landmark into a poetic vision of impermanence and renewal. By embracing the city’s industrial motifs within the framework of Impressionist observation, Monet demonstrates the enduring power of art to bridge modernity and nature. Over a century later, Charing Cross Bridge remains a masterful exploration of perception, mood, and the fleeting beauty of dawn mist on the Thames.