Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “Ceres and Two Nymphs with a Cornucopia”

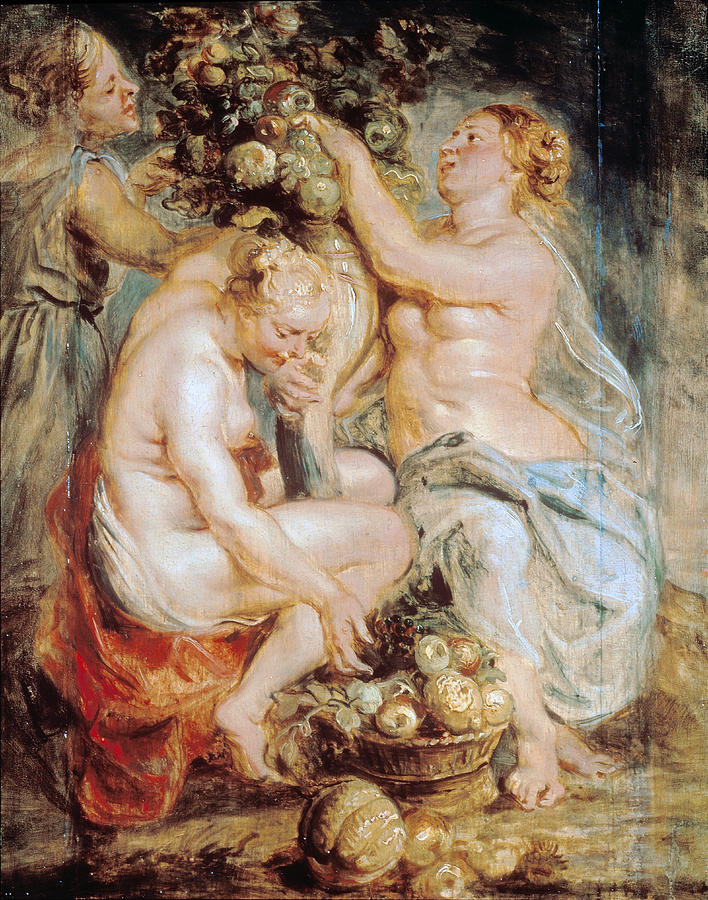

“Ceres and Two Nymphs with a Cornucopia” is a lush allegorical painting attributed to Peter Paul Rubens that celebrates fertility, harvest, and the generous nourishment of the earth. Three female figures cluster around an enormous cornucopia bursting with fruit. One is clearly Ceres, Roman goddess of agriculture, while the other two are nymphs or attendants who help gather and arrange the harvest bounty. The scene is intimate and crowded, with intertwined bodies, overflowing baskets, and the tactile presence of ripened produce.

In this work Rubens brings together several of his trademarks: voluptuous, living bodies; a glowing palette; and a dynamic surface where paint itself seems to swell and ripple like the forms it describes. Rather than presenting Ceres as a distant, idealized deity, he throws the viewer into the midst of the harvest, almost close enough to touch the fruit and feel the warmth of the figures’ skin.

Ceres And Her Symbolic Role

Ceres sits at the center of the group, slightly bent forward, her body wrapped loosely in a red drapery that leaves much of her torso bare. In classical mythology she presides over grain, fertility of the fields, and the cycle of growth and reaping. Here, however, the emblem is not grain but fruit, which expands her symbolic domain to include abundance in general.

Her pose is thoughtful: she leans forward, head inclined, one hand near her mouth as if in contemplation, while the other reaches toward the basket of fruit. This slight introspective gesture distinguishes her from the more outwardly active nymphs. She is not merely a worker among workers but the divine source from which the harvest flows.

The red drapery around her reinforces her status. Red in Baroque painting often signals vitality, power, and the life-blood of nature. Against the pale flesh of her body, the cloth glows like a ripe fruit itself, making her the visual heart of the composition.

The Two Nymphs As Agents Of Abundance

Flanking Ceres are two nymphs, each contributing to the energetic mood of the scene. On the right, a nearly nude figure wrapped in pale blue cloth kneels beside Ceres. She lifts fruit toward the overflowing vessel above, her body turning upward in a twisting motion that reveals the weight and softness of her form. Her raised arm and tilted head introduce an upward thrust that counterbalances Ceres’s downward curve.

On the left, another attendant, more clothed, leans in from behind, reaching toward the towering mass of fruit. She is slightly more distant and partially obscured, yet her presence completes the triangular arrangement of figures. Her grayish dress and darker tones recede behind the brighter flesh tones of Ceres and the right-hand nymph, helping to frame the central action.

Together, the two nymphs act as extensions of Ceres herself. They gather, arrange, and display the bounty, translating divine fertility into tangible offerings. Their lively gestures and close proximity create an atmosphere of bustling collaboration.

The Cornucopia And Overwhelming Fruitfulness

The dominant object in the scene is the enormous cornucopia, which swells upward like a living tree of fruit. Rubens piles apples, grapes, gourds, and other produce into a dense, almost sculptural mass that rises above the women’s heads. The horn itself is partly obscured by bodies and fruit, but its spiraling form can be traced as it twists from the lower right, through Ceres’s lap, into the monumental heap above.

At the bottom of the composition, a basket brims with more fruit, and additional melons and vegetables spill onto the ground. There is a sense that no container is large enough; the harvest keeps overflowing, unconstrained by human attempts to gather it.

The choice of fruit is significant. Apples and grapes recall both classical myths of divine feasts and Christian associations with paradise and wine. Their round forms echo the curves of the women’s bodies, visually linking physical beauty to natural abundance. The mix of smooth-skinned fruits and more textured melons provides a rich variety of surfaces for Rubens to explore with his brush.

Composition And Interlocking Forms

The composition radiates from the central mass of fruit and figures. There is little empty space; everything is filled with flesh, cloth, or produce. This density contributes to the feeling of plenty. The three women form a closed circle around the cornucopia, their limbs and torsos overlapping so thoroughly that it can be difficult to separate one from another at first glance.

Rubens arranges their bodies in a complex interlock of curves. Ceres bends forward, her back rounding; the right-hand nymph arches upward; the left-hand figure leans diagonally into the scene. These movements create a swirling rhythm that keeps the eye moving around the canvas. At the same time, repeated circular shapes—the rounded shoulders, bent knees, and spherical fruits—reinforce the theme of fullness and cyclical growth.

The lower part of the painting is anchored by Ceres’s tucked legs and the heavy basket of fruit, while the upper area is dominated by the vertical rise of the cornucopia. The overall effect is that of a living pyramid, broader at the base and narrowing toward the top, but animated by internal movement.

Light, Color, And Sensual Atmosphere

Rubens’s color palette here is warm and earthy, perfectly suited to the subject. Flesh tones range from rosy pinks to creamy highlights and subtle golden shadows. The fruit shares similar hues, especially the apples and peaches whose skins mirror the women’s complexions. This chromatic echo strengthens the association between human bodies and the produce of the earth.

The red drapery around Ceres and the orange-brown cloth beneath the group add vivid accents, while the cooler blue of the right-hand nymph’s cloth provides contrast. The background is loosely defined in muted browns and greens, setting off the warm tones of the foreground without drawing attention away from the main action.

Light seems to fall from the left and above, catching the tops of the fruits, the nymphs’ shoulders, and Ceres’s head. Highlights are applied with confident, thick strokes, giving surfaces a moist, tactile shine. The interplay of light and shadow across the intertwined bodies contributes to a sensual atmosphere: skin glows, fruit gleams, and even the folds of fabric appear lush and weighty.

Brushwork And The Painterly Surface

One of the most striking aspects of this painting is its energetic brushwork. Unlike a meticulously smoothed academic finish, Rubens allows his strokes to remain visible, especially in the background and less focal areas. Swirls of paint create the mass of fruit, the texture of drapery, and the general environment.

This painterly freedom suggests that the work may be a sketch or modello, possibly made as a preparatory design for a larger composition or decorative program. Yet even if it served as a study, it is remarkably complete in its expression of theme and mood.

Thicker passages of paint model the women’s flesh, with subtle transitions between light and shadow that capture the softness and weight of their bodies. In contrast, the fruits and basket often appear with quicker, more suggestive strokes, emphasizing their quantity and variety rather than precise botanical detail. The result is an overall impression of life and movement rather than static description.

Ceres As Earth Mother And Baroque Ideal

Rubens’s Ceres typifies his broader ideal of feminine beauty: full-bodied, robust, and radiating health. Far from the slender, ethereal figures that would become fashionable in later centuries, his women embody physical strength and the capacity to nourish. This aesthetic is closely tied to the painting’s symbolism. A thin, fragile goddess would be an unlikely guardian of harvest and fertility; a sturdy, fertile figure better suits the theme.

The earth-mother quality of Ceres is reinforced by her posture. She is physically close to the ground, squatting or sitting low rather than perched on a throne. Her hand reaching toward the basket connects her directly with the fruits of the earth. Yet the crown-like arrangement of her hair and the dignity of her expression keep her within the realm of the divine.

The right-hand nymph, similarly ample and lively, mirrors this ideal. Together, the two nudes present a vision of womanhood that is unabashedly material and sensual, yet linked to cosmic cycles of growth and harvest.

Allegorical Layers And Possible Meanings

At its simplest level, “Ceres and Two Nymphs with a Cornucopia” celebrates agricultural abundance and the pleasures of plenty. However, Baroque allegories often carried multiple layers of meaning, especially when created for aristocratic patrons.

The cornucopia and fruit could stand for the prosperity of a particular realm, suggesting that under wise rule, the land flourishes. Ceres might then be seen not only as goddess but as an allegorical portrait of a queen or noblewoman whose governance brings wealth to her people.

The three female figures might also correspond to broader concepts such as the seasons, different stages of the harvest (gathering, sorting, consuming), or even virtues like generosity and gratitude. While the painting does not spell out any single reading, its imagery would have encouraged viewers to link natural plenty with social and moral order.

Emotional Tone And Viewer Engagement

The emotional tone of the painting is one of robust joy, tinged with a reflective calm in Ceres’s downward gaze. The nymphs’ active engagement with the fruit—reaching, lifting, and arranging—gives the scene an element of cheerful work, akin to a harvest festival. At the same time, the close grouping of figures creates intimacy; the viewer looks in on a private, almost domestic moment among divine beings.

Rubens invites viewers to participate not only visually but almost physically. The large, foregrounded fruits and the proximity of the figures to the picture plane make us feel as though we could reach out to share in the harvest. The sensuous handling of paint, which emphasizes touch and texture, further heightens this effect.

Relation To Rubens’s Other Allegories Of Plenty

Rubens returned repeatedly to themes of abundance, peace, and prosperity, often using similar motifs: cornucopias, fruit-bearing figures, and full-bodied nudes. Works such as “Abundance,” “Peace and Abundance,” and various depictions of the goddess Fortuna show his ongoing interest in visualizing plenty as a combination of natural fertility and divine favor.

“Ceres and Two Nymphs with a Cornucopia” fits squarely within this tradition but distinguishes itself through its particularly intimate scale and intense crowding of forms. Where some allegories include expansive landscapes or additional symbolic figures, this painting concentrates on the immediate, tangible presence of harvest goods and the bodies that gather them. It feels less like a public monument and more like a private celebration of the pleasures that plenty affords.

Conclusion

“Ceres and Two Nymphs with a Cornucopia” is a vivid expression of Peter Paul Rubens’s Baroque vision of abundance. Through the intertwined bodies of Ceres and her attendants, the towering cornucopia, and the overflowing baskets of fruit, he creates a world where nature’s generosity is palpable and ever-renewing.

The painting’s warm colors, dynamic composition, and lively brushwork all reinforce its central message: that the earth, under the care of divine and human hands, can yield more than enough to nourish and delight. At the same time, the work serves as a sophisticated allegory that could speak to ideas of good governance, peace, and the virtues of a prosperous society.

For modern viewers, the painting offers both sensory pleasure and historical insight. It reveals how a seventeenth-century artist used mythological imagery to explore fundamental human hopes—food, safety, celebration—and how he transformed those themes into a richly painted vision of life at its most generous.