Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

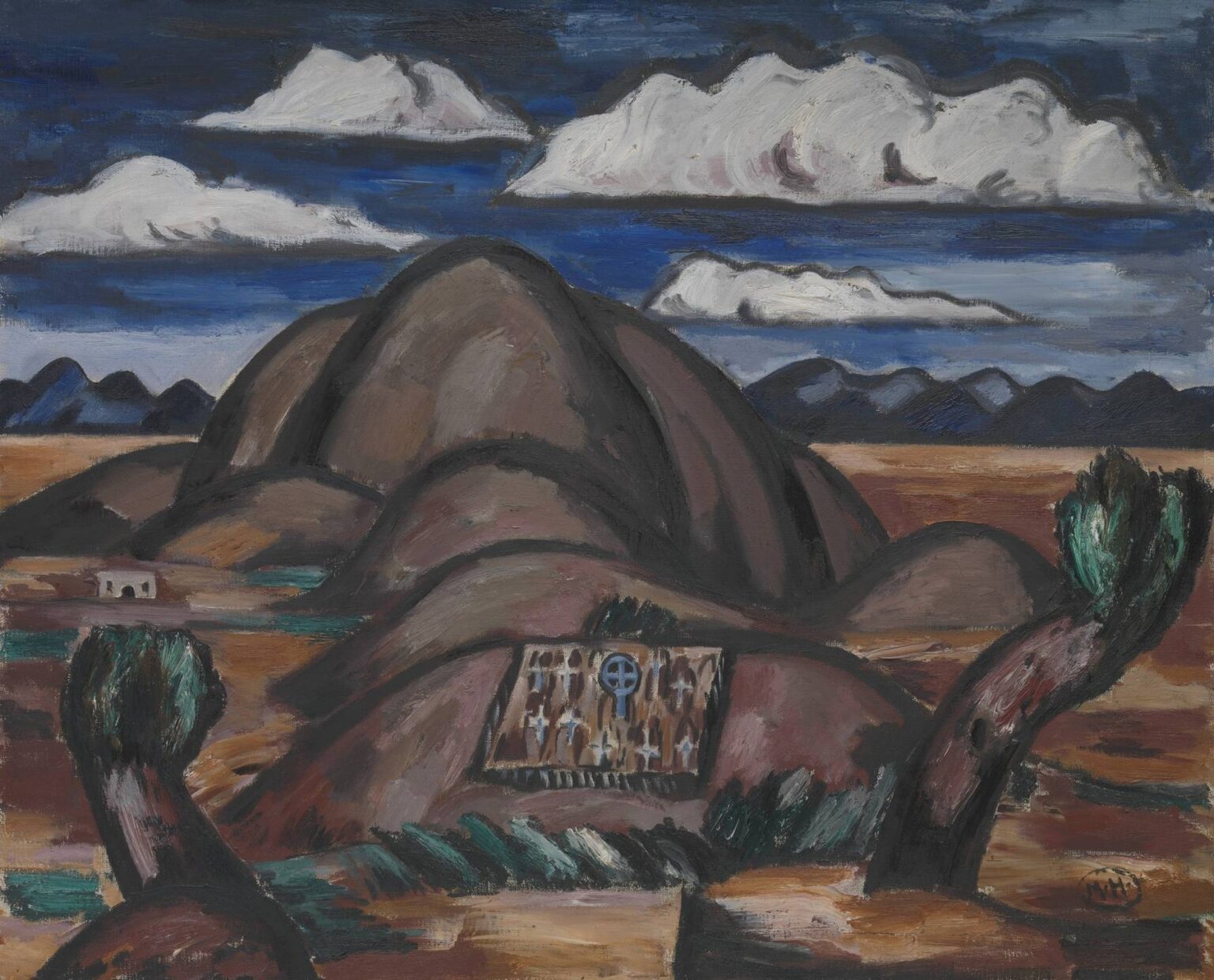

Marsden Hartley’s Cemetery, New Mexico (1924) stands as a luminous testament to the artist’s visionary engagement with the American Southwest. In this canvas, Hartley transforms an austere desert burial site into a resonant tapestry of form and color, melding ancient adobe architecture with a modernist aesthetic purged of extraneous detail. The painting’s central motif—a simple earthen mound draped in an embroidered cloth—anchors a composition that simultaneously celebrates the sacredness of place and probes broader themes of mortality, memory, and cultural encounter. From the twisted, sentinel‑like trees that frame the foreground to the rolling, undulating hills in the middle ground, all the way to the distant mountain crest beneath a brilliant, cloud‑strewn sky, Hartley’s arrangement evokes both the material reality of New Mexico’s high desert and the spiritual echoes embedded within its landscape.

Hartley’s Southwestern Journey and Its Significance

In the spring of 1924, Marsden Hartley embarked on an expedition through New Mexico and Arizona, sponsored by Alfred Stieglitz’s Circle members at Gallery 291. This journey represented a departure from the Vermont and Maine motifs that had anchored his earlier career, offering instead a new world of adobe pueblos, Puebloan and Hispano burial grounds, and the startling clarity of the desert sun. Equipped with sketchbooks, watercolors, and a restless curiosity, Hartley immersed himself in the region’s vernacular architecture, indigenous and Hispano customs, and the vast, seemingly empty spaces that stretched to the horizon. His preliminary studies—quick washes capturing the ochre hues of sun‑baked earth or the crisp geometry of adobe walls—served as raw materials for the studio paintings he completed upon returning to New York. Among these, Cemetery, New Mexico crystallizes his dual impulse to document a regional tradition while transcending mere ethnographic portrayal through the language of modernist form.

The Confluence of Tradition and Modernism

Hartley’s approach in Cemetery, New Mexico reveals an artist at the confluence of two seemingly disparate currents: a deep respect for local, lived traditions and a fearless embrace of modernist experimentation. The adobe mound draped in a cloth embroidered with crosses and a quatrefoil window motif speaks to a living Hispano funerary custom, one grounded in Catholic iconography and centuries‑old craft. Yet Hartley reconfigures these time‑honored elements into bold, simplified shapes. The mound’s rounded mass becomes almost sculptural, the embroidery reduced to pattern and color, the trees abstracted into twisting vertical accents. By flattening spatial depth and eliminating superfluous detail, Hartley elevates his subject beyond documentary fidelity, inviting viewers to experience the cemetery not only as a geographic site but also as a symbol of human rites and the passage of time.

Structural Composition and Rhythmic Balance

At the heart of Cemetery, New Mexico lies a carefully orchestrated composition that balances curvature and vertical thrust, horizontality and diagonal movement. The central adobe mound curves gracefully across the mid‑section of the canvas, its rounded edges echoed by the gently arcing hills that recede beyond it. These hills step down in a rhythmic cadence, guiding the eye from the mound’s base toward a distant ridge whose serrated silhouette marks the horizon. In the foreground, two gnarled trees rise on either side—anchors that frame the scene and lend a sense of human presence, as if these arboreal forms themselves stand vigil over the dead. Their knotted trunks and upward‑reaching branches create a visual counterpoint to the horizontal sweep of the land, injecting energy and tension into an otherwise solemn tableau. The sky overhead forms a wide, horizontal band, its deep ultramarine pierced by streaks of white cloud that seem to drift toward the painting’s edges, reinforcing the idea of the cemetery as a crossroads between earth and sky.

Chromatic Vibrancy and Desert Atmosphere

Color operates as a primary vehicle for meaning in Cemetery, New Mexico. Hartley’s palette draws heavily on the high desert’s sun‑baked earth: burnt sienna, raw umber, and golden ochre suffuse the ground, while the adobe form itself bears subtle mixtures of tan, gray, and russet that capture centuries of weathering. Vegetation at the base of the mound appears as squiggling strokes of teal and olive, a reminder of life persisting in harsh conditions. The middle ground’s hills recede in paler purples and muted browns, their tonal diminution lending depth through atmospheric perspective. Above, the sky’s ultramarine intensifies the painting’s emotional charge; bold sweeps of pure cobalt are undercut by lavender and slate in the cloud forms, suggesting both the permanence of geological time and the transience of human existence. Hartley layered thin glazes over denser passages, allowing earlier hues to peek through and unifying the work with a shimmering, jewel‑like surface that evokes the desert’s mirage‑like luminosity.

Texture, Brushwork, and the Materiality of Paint

Hartley’s brushwork in Cemetery, New Mexico testifies to his tactile engagement with paint as a medium. The adobe mound emerges from thickly applied, rounded strokes that emphasize its solidity, as if hewn from the canvas itself. The embroidered cloth’s intricate cross motifs result from small, stippled touches that recall threadwork, while the scrub vegetation is evoked through quick, broken strokes that convey fragility and movement. The trees’ bark and knots are suggested by whorls of darker paint, imparting a sense of rough, living texture. In the sky, horizontal scumbles and flicks of white produce cloud forms of varying opacity, their edges blending softly into the surrounding blue. Throughout, Hartley leaves occasional glimpses of the raw, unpainted canvas in shadowed interstices, underscoring the painting’s status as both object and illusion. This interplay between impasto and transparency, between the surface’s physicality and its pictorial depth, reflects Hartley’s mastery of paint as both material and message.

Symbolism and the Universal Resonance of Place

While deeply rooted in the specifics of New Mexico’s Hispano burial traditions, Cemetery, New Mexico transcends its locale to evoke universal questions of life, death, and remembrance. The simple earth mound can stand as a universal symbol of mortality, its draped cloth recalling shrouds used in death rites across cultures. The embroidered crosses and quatrefoil window motif point toward Christian resurrection iconography, yet their reduction to pattern invites broader spiritual interpretations. The two sentinel trees might be read as mourners or guardians, their arched forms echoing the cross and the path from earth to heaven. By stripping the scene to its essential forms and rhythms, Hartley invites contemplation on the human impulse to honor the dead, to carve meaning from the void, and to seek continuity beyond individual lifespans. In this sense, the painting functions as a secular sacred object—a canvas that channels the power of ritual into the realm of modernist abstraction.

Relation to Hartley’s Broader Body of Work

Cemetery, New Mexico occupies a key position in Hartley’s artistic trajectory, linking his earlier Berlin Officer portraits—characterized by bold outlines and symbolic motifs—with his later Maine landscapes and abstract works. His German period (1913–15) had introduced an austere, emblematic style that harnessed geometric shapes and flat color fields to convey personal and political allegory. In New Mexico, he redirected this approach toward the landscape, substituting military insignia for adobe forms and cultural symbols. Upon returning East, Hartley continued to explore burial grounds and church exteriors in Maine, often revisiting the themes of death and ritual first encountered in the Southwest. In his late abstractions, totemic motifs and rhythmic patterns of Cemetery, New Mexico reappear in distilled form, demonstrating the painting’s lasting influence on his evolving visual vocabulary.

Hartley’s Place in American Modernism

In the early 1920s, American art was undergoing a search for identity beyond European models. Hartley’s Southwestern paintings offered one solution: a modernist fusion of avant‑garde form with distinctly American subject matter. Cemetery, New Mexico exemplifies this synthesis, as Hartley applied Cubist flattening, Expressionist color intensity, and Symbolist allusion to a regional scene. His respectful, contemplative portrayal of Hispano burial practices contrasted with the more touristic or primitivist approaches of some contemporaries. By honoring local customs while advancing formal experimentation, Hartley contributed to the development of an authentically American modernism—one that embraced the nation’s diverse cultures and landscapes rather than importing alien tropes.

Reception and Ongoing Legacy

Upon its exhibition at Gallery 291, Cemetery, New Mexico drew critical attention for its bold departure from Hartley’s prior subjects and its inventive combination of ethnographic detail with modernist abstraction. Over the ensuing decades, the painting has been recognized as a foundational work in the American Southwestern canon, studied by scholars of both art history and cultural anthropology. Contemporary exhibitions frequently pair Cemetery, New Mexico with Hartley’s Maine landscapes to highlight his dual commitments to place and innovation. For twenty‑first‑century viewers, the canvas resonates with renewed urgency: questions of cultural appropriation, environmental stewardship, and the preservation of communal memory underscore the painting’s complex interplay between indigenous traditions and outsider interpretation. As institutions mount retrospectives of Hartley’s career, Cemetery, New Mexico remains a centerpiece—for it encapsulates the artist’s boldest experiments in bridging worlds, honoring the past, and charting new paths in American art.

Conclusion

Marsden Hartley’s Cemetery, New Mexico (1924) endures as a pinnacle of his Southwestern oeuvre and a landmark of early American modernism. Through its harmonious synthesis of adobe forms, embroidered ritual cloth, twisted arboreal sentinels, and arid vistas under a luminous sky, the work transforms a simple burial mound into a universal meditation on mortality, memory, and spiritual transcendence. The painting’s flattened space and rhythmic patterns absorb modernist innovations, while its evocation of specific Hispano customs grounds it in a living cultural tradition. In fusing the local with the avant‑garde, Hartley forged a visual language that resonates far beyond New Mexico’s high desert—to all who seek meaning in the meeting of earth and sky, of life and death, of art and ritual.