Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

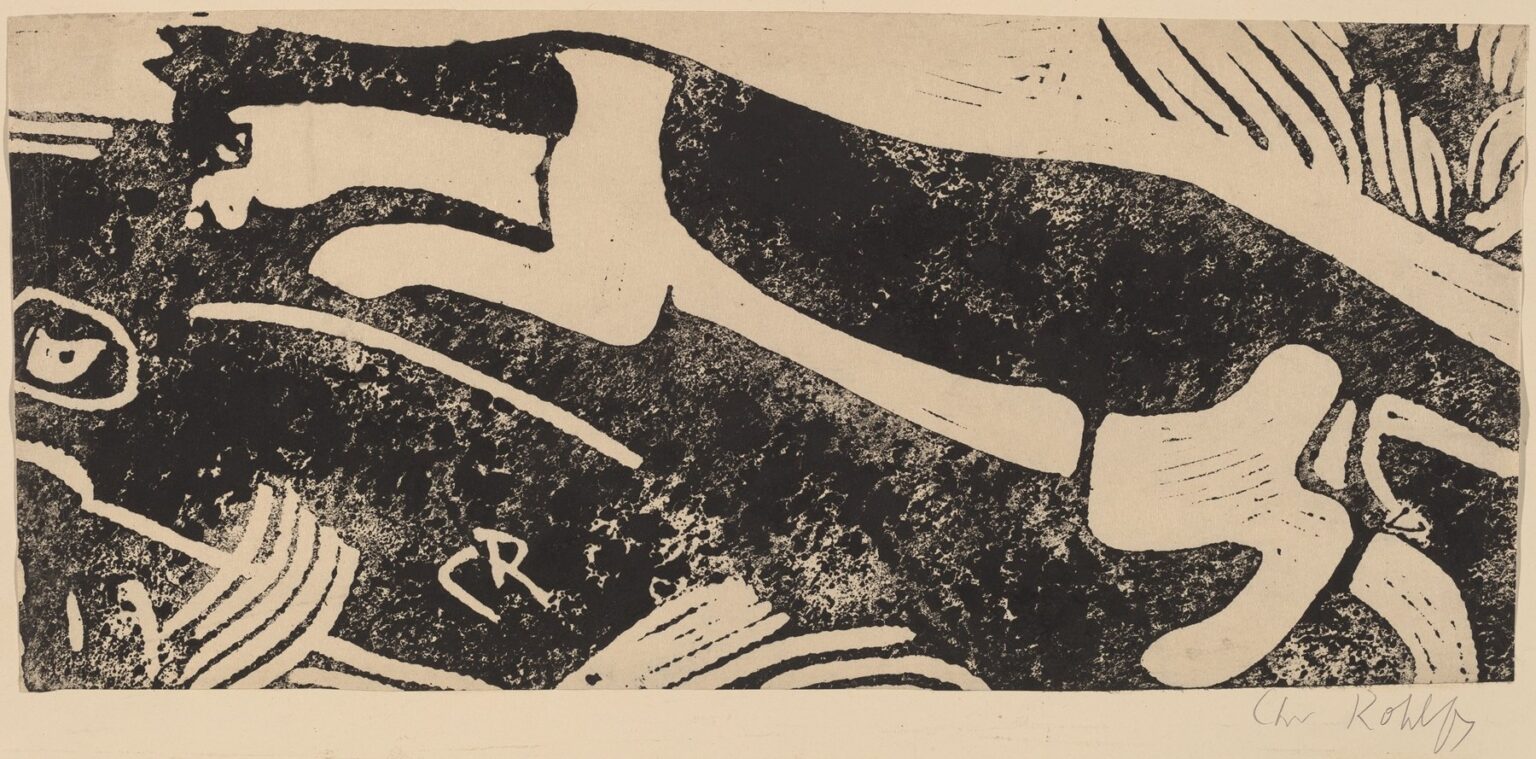

In 1913, Christian Rohlfs produced “Cat and Mouse,” a striking print that distills the eternal drama of predator and prey into a language of bold shapes and expressive texture. Executed on paper in stark black on a cream ground, this work transcends mere illustration to become a meditation on conflict, survival, and the oscillations between dominance and vulnerability. Rohlfs, already an established figure in German art circles, harnessed the immediacy of printmaking to explore themes of tension and playfulness, setting the stage for his later, more overtly Expressionist endeavors. The following analysis delves into the painting’s cultural and artistic context, traces Rohlfs’s evolution leading up to 1913, and examines in depth the formal qualities, symbolic resonances, and lasting legacy of this enigmatic composition.

Historical Context of Early 20th-Century Germany

By 1913, Europe stood on the brink of seismic change. The rapid industrialization of the late 19th century had given way to social upheaval, and artists across Germany sought new modes of expression to capture the psychological undercurrents of modern life. The avant-garde movements—Jugendstil, Die Brücke, and Der Blaue Reiter—challenged academic conventions, experimenting with color, form, and printmaking techniques. Christian Rohlfs, born in 1849, had already witnessed the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the first stirrings of Expressionism. Though older than many of his contemporaries, he remained open to innovation, adopting woodcut and linocut printmaking to achieve more immediate, graphic results. “Cat and Mouse” emerged from this crucible of formal experimentation and cultural anxiety, reflecting both a return to elemental subject matter—animal figures—and a bold rethinking of representation.

Christian Rohlfs’s Artistic Trajectory

Christian Rohlfs’s career spanned over six decades, during which he moved from Naturalism and Romantic landscape painting toward a radical abstraction of form and color. His early training at the Düsseldorf Academy instilled a respect for disciplined draftsmanship and tonal subtlety. However, a pivotal visit to Paris in 1903 exposed him to the daring color experiments of the Fauves and the raw immediacy of woodcuts by Émile Bernard. Back in Germany, Rohlfs began incorporating flat color areas and simplified contours into his work, anticipating Expressionism’s focus on emotional truth over optical fidelity. By 1913, he had mastered printmaking to the point where a single black-and-white image like “Cat and Mouse” could communicate not only a narrative moment but a deep psychological resonance. The predator-prey motif offered an ideal metaphor for human conflict, while the print medium allowed Rohlfs to exploit high-contrast forms and tactile surfaces.

Formal Composition

At first glance, “Cat and Mouse” presents two abstracted silhouettes: the cat occupies the upper third of the composition, elongated and lithe, while the mouse lurks at the bottom, its tiny form dwarfed by the feline’s imposing mass. Rohlfs arranges these figures along a diagonal axis, as if the cat, stalking from left to right, is about to pounce on the unsuspecting rodent. This dynamic tilt injects tension and narrative momentum. Yet the composition is anything but literal. The cat’s body is rendered as a series of sweeping black curves with textured interiors, rather than a faithful anatomical depiction. The mouse appears as a simple, rounded shape punctuated by a few linear marks suggesting a tail or whiskers. Negative space—areas of untouched cream paper—serves as background, allowing the black forms to float. This minimal embrace of space underscores the existential isolation of both hunter and hunted, evoking a tableau that feels timeless and universal rather than bound to a specific moment or locale.

Technique and Surface Texture

“Cat and Mouse” employs the woodcut or linocut technique—printmaking methods that involve carving away non-image areas from a block and then inking the remaining surface. Rohlfs’s carving marks remain visible in the final print, imparting an expressive roughness to the black areas. Some regions appear densely saturated, their inky surfaces near-solid, while others reveal a mottled texture where the ink skimmed unevenly over carved grooves. This variegation lends the animals a palpable vitality: the cat’s sleek back suggests both sleekness and the bristling anticipation of movement, while the mouse’s fragile outline trembles with vulnerability. The stark dichotomy of black and cream heightens the dramatic stakes, aligning the viewer’s gaze with the stark moral clarity of predator and prey. Yet the textured surfaces add complexity, reminding us that neither role is simple or one-dimensional.

Color, Contrast, and Visual Impact

The radical reduction to monochrome intensifies “Cat and Mouse”’s visual impact. Without color to distract or embellish, the viewer confronts the essence of form and the drama of contrast. Black against cream creates a tension not unlike the cat’s poised threat over its quarry. The use of unmodulated black—save for the carved textures—emphasizes silhouette over detail, compelling the eye to register movement and gesture rather than anatomical specifics. In this way, Rohlfs channels the raw immediacy of woodcut’s folk-art origins while pushing its expressive potential. The tonal extremes also echo the era’s fascination with psychological dualities—light and dark, conscious and unconscious, hunter and hunted—anticipating the darker moods that Expressionism would soon explore through color.

Symbolism and Allegory

On the surface, “Cat and Mouse” may simply depict an animal encounter. Yet beneath its stark imagery lies a rich allegorical dimension. The cat, powerful and predatory, can be read as a symbol of human aggression, the instinct to dominate or consume. The mouse stands for innocence and fragility, the precariousness of existence in a world governed by stronger forces. In pre–World War I Europe, such themes resonated deeply: nations jostled for power, individuals navigated rapid social change, and the specter of conflict loomed large. By choosing an animal fable stripped to its bare essentials, Rohlfs evokes Shakespeare’s invocation in King Lear—“Poor naked wretches”—reminding viewers that beneath veneer and civilization lie primal drives. Yet there is room for ambiguity: the mouse’s smallness might also inspire empathy or defiance, challenging the cat’s assumed superiority. In this tension, the print becomes a mirror for the viewer’s own moral and psychological struggles.

Psychological and Emotional Resonance

Beyond its allegorical thrust, “Cat and Mouse” possesses a raw emotional charge. The diagonal composition and contrasting masses create an anxiety-laden rhythm: the cat’s curves sweep downward with insinuating menace, while the mouse’s small form seems caught in a moment of frozen alarm. The visible carving textures impart a sense of urgency, as if the image itself bears witness to a rapid, decisive moment. Viewers may feel a kinship with the mouse’s plight or be drawn to the cat’s taut energy. The painting plays on universal fears and fascinations: fear of being overpowered, thrill of the chase, the delicate balance of power in any relationship. In this way, Rohlfs anticipates the later Expressionist focus on inner states, suggesting that emotion can be conveyed not only through facial expressions or color but through formal dynamics of shape, line, and space.

Place in Rohlfs’s Oeuvre

“Cat and Mouse” marks a pivotal moment in Christian Rohlfs’s trajectory. While he had experimented with woodcuts earlier, this 1913 work represents one of his most accomplished statements in the medium. It bridges his earlier figural and landscape prints—where he retained more representational detail—and his late oil paintings bursting with nonobjective color. Comparisons can be drawn between this image and Rohlfs’s later, more abstract animal motifs, in which forms dissolve into rhythmic patterns of brushwork. In each case, Rohlfs returns to animal subjects as a locus for exploring tension, vulnerability, and elemental drama. “Cat and Mouse” thus functions as a key transitional piece, illustrating how Rohlfs could compress narrative to its core and harness printmaking’s immediate impact to channel the emotional intensity that would define German Expressionism.

Influence and Legacy

Although Christian Rohlfs is sometimes overshadowed by younger Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Franz Marc, prints such as “Cat and Mouse” reveal his crucial role in advancing the movement’s formal and thematic concerns. His mastery of woodcut technique—embracing visible carving marks, stark contrasts, and simplified shapes—inspired contemporaries and later artists to reconsider the graphic medium’s expressive power. Indeed, the interwar years saw a flourishing of Expressionist printmaking in Germany, with Rohlfs’s prints often cited alongside those of Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Today, “Cat and Mouse” is recognized not only for its narrative potency but as a milestone in the history of early twentieth-century print art—an exemplar of how a single sheet of paper can conjure profound emotions and complex philosophical questions.

Conclusion

Christian Rohlfs’s “Cat and Mouse” (1913) remains a tour de force of Expressionist printmaking. Through a masterful reduction to silhouette, texture, and dynamic composition, the work evokes the primal tension of predator and prey while opening broader allegorical and psychological vistas. Rooted in the socio-political ferment of pre–World War I Germany and in Rohlfs’s own evolution from academic realism to avant-garde experimentation, this print captures a moment when form and emotion coalesce in stark, unforgettable contrast. As both a narrative fable and a formal abstraction, “Cat and Mouse” continues to resonate, reminding viewers of art’s power to distill life’s dramas into potent, enduring images.