Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Peter Paul Rubens’ “Bust of Seneca”

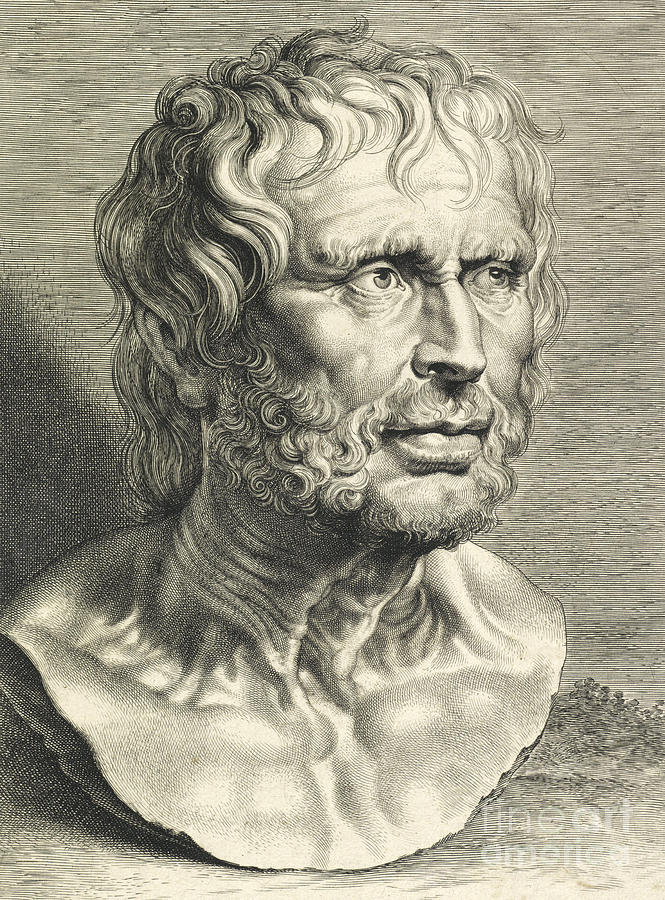

“Bust of Seneca” attributed to Peter Paul Rubens is a compelling study of an antique head that reveals as much about the Baroque painter’s intellect as it does about the ancient philosopher he depicts. The image shows a powerful male head and upper chest, treated like a sculpted marble bust: no clothing, the shoulders roughly cut off at the base, the face tilted slightly upward and to the right. Rendered in meticulous lines, the portrait combines archaeological interest, anatomical precision, and a deep fascination with human character.

Whether executed as a drawing, an engraving design, or a close study of a classical sculpture in Rubens’ collection, “Bust of Seneca” belongs to a long tradition of artists looking back to antiquity for models of moral and physical strength. The intense gaze, furrowed forehead, and gaunt neck transform the Roman writer Seneca into a vivid embodiment of Stoic thought—someone who has suffered, reflected, and endured.

Rubens and the Classical World

Rubens spent formative years in Italy, where he immersed himself in ancient sculpture and Renaissance interpretations of classical themes. Throughout his life he collected casts, reliefs, and antique busts. These objects were not mere decorations; they served as models, sources of inspiration, and anchors for Rubens’ own intellectual identity as a humanist painter.

The choice of Seneca is revealing. Lucius Annaeus Seneca, the Roman statesman and Stoic philosopher, was admired in the seventeenth century for his writings on ethics, fate, and the discipline of the soul. For Catholic humanists like Rubens, Seneca represented a pre-Christian moral thinker whose insights could align with Christian virtue—particularly endurance in suffering and contempt for worldly excess. Depicting Seneca’s bust allowed Rubens to signal his own erudition and moral interests while also practicing the study of sculptural form.

Subject and Identification of Seneca

In “Bust of Seneca,” the philosopher is shown as a rugged, aging man. His hair is short and tousled, receding from a high forehead; a curly beard surrounds his mouth and chin; deep lines mark his brow and cheeks. The neck is sinewy, the collarbones sharply defined, the skin over the chest stretched tight as if the body were lean and muscular rather than fleshy. This is not the smooth ideal beauty of a Greek god but the weathered face of a thinker who has confronted hardship.

Seventeenth-century viewers would have associated such a head with Seneca thanks to widely circulated antique busts believed to represent him. Modern scholarship questions some of these identifications, but for Rubens’ contemporaries the type—a lined, ascetic face with tousled hair—was firmly tied to the Stoic writer. Rubens’ study thus participates in the construction of Seneca’s visual identity as the archetypal philosopher of endurance.

Composition and Point of View

The composition is tightly focused. The bust fills almost the entire vertical space, and the background is reduced to fine horizontal lines that recede into neutral tone. This minimal setting pushes the viewer’s attention entirely onto the head and upper torso.

Rubens positions the bust slightly turned to the right and tilted upward. This three-quarter view allows him to show both eyes, the full profile of the nose, the strong jaw, and the complicated planes of the neck. The upward tilt gives Seneca a searching, visionary quality, as if he is contemplating something beyond the viewer’s sight. At the same time, the vantage point from slightly below emphasizes the volume of the head and creates a sense of monumentality.

The base of the bust is only roughly indicated, with chisel-like cuts around the shoulders and chest. This unfinished edge enhances the illusion that we are looking at stone rather than a living body, while still letting Rubens explore the anatomy of collarbones and muscles.

Line, Hatching, and the Illusion of Sculpture

One of the most impressive aspects of “Bust of Seneca” is Rubens’ mastery of line. The entire image is built from fine, controlled strokes that vary in density and direction. Rather than modeling with tone or color, he uses parallel lines and cross-hatching to create volume, texture, and light.

On the forehead and cheeks, the lines curve gently to follow the shape of the skull and facial muscles. In deeper shadows—under the chin, in the hollow of the neck, around the eye sockets—the hatching becomes denser and more tightly packed, producing almost velvety darkness. Lighter areas, such as the bridge of the nose and the top of the shoulders, have more open spacing, allowing the paper to shine through and suggest reflected light.

This approach echoes printmaking techniques. Whether Rubens himself engraved the plate or designed it for a specialist engraver, the image shows an intimate understanding of how linear systems can mimic three-dimensional forms. The result is that the bust seems almost tangible: one can sense the cold hardness of marble yet also imagine the living flesh beneath.

Anatomy and the Baroque Fascination with the Body

Rubens was famous for his robust, dynamic figures, and even in this static bust he demonstrates a keen grasp of human anatomy. The muscles and tendons of the neck are carefully delineated, showing the sternocleidomastoid cords, the hollow above the clavicles, and the subtle bulge of the throat. These details contribute to the impression that Seneca is tense, his muscles tightened as if he is about to speak or has just finished an impassioned argument.

The chest is rendered with broad, smooth planes crossed by gentle hatching. Although the shoulders are cut off as if carved, Rubens still suggests the underlying pectoral muscles and rib cage. This combination of sculptural truncation and lifelike anatomy reflects Baroque interest in the interplay between artifice and living nature.

The face, too, is anatomically convincing. Creases on the forehead follow the pull of the frontalis muscle; crow’s feet radiate from the corners of the eyes; the cheeks are slightly sunken, emphasizing the zygomatic bone and the jaw. The mouth is slightly open, revealing the suggestion of teeth and tongue, a small but powerful sign of speech.

Facial Expression and Psychological Depth

Perhaps the most captivating feature of “Bust of Seneca” is the philosopher’s expression. His eyes are wide and intense, looking slightly upward and into the distance. The furrowed brow, raised eyebrows, and parted lips suggest a mind in motion, wrestling with thought or emotion. He seems caught at a moment when an insight has struck him or when he is defending a position with passionate conviction.

This psychological tension is enhanced by the contrast between the aged skin and the vigorous musculature. Deep lines around the eyes and mouth speak of years of worry or contemplation, yet the neck and chest remain taut and strong. Rubens thereby conveys both the fragility and resilience of human life—a theme well suited to Seneca, whose writings often emphasize the brevity of existence and the need to cultivate inner strength.

Unlike idealized portraits where serenity reigns, this head is full of restlessness. It invites viewers to imagine the philosopher’s inner dialog, his struggles with imperial politics, exile, and forced suicide. The expression aligns with Baroque culture’s fascination with intense feeling and moral drama.

Light, Shadow, and the Sense of Presence

Although the work is monochrome, Rubens uses light and shadow to dramatic effect. Illumination seems to come from the upper left, striking the forehead, nose, cheekbones, and upper chest. Shadows fall across the right side of the face, under the eyebrows, and beneath the chin, creating a strong chiaroscuro that sharpens the features.

This lighting not only models the forms but also contributes to the emotional tone. The bright areas highlight the creases and wrinkles, exposing the marks of age, while the shadows deepen the eye sockets and mouth, giving Seneca a slightly haunted appearance. The pattern of light and dark guides the viewer’s gaze from forehead down the nose to the mouth and then across the neck and shoulders.

The neutral background, built from horizontal lines that fade toward the edges, keeps the eye from wandering. There is no scenery, no symbolic attribute, only the head floating in space. This isolation intensifies the sense of presence: Seneca appears to emerge from darkness into thought, as if summoned out of time for contemplation.

Classical Model and Baroque Interpretation

Rubens’ study is likely based on an actual Roman bust that he knew, either in his collection or in a collection he had studied in Italy. Antique portrait busts often aimed to capture both likeness and character through realistic details of age and expression. Yet Rubens, as a Baroque artist, infuses this inherited type with additional movement and psychological energy.

Compared to many ancient portraits, which can seem stoic or impassive, Rubens’ Seneca is more animated. The twist of the head, the open mouth, the pronounced furrows—all are heightened to convey drama. This does not necessarily mean he distorts the classic model; rather, he interprets it through his own era’s sensibilities, emphasizing interior life over outward decorum.

In this way, “Bust of Seneca” bridges two artistic ideals: the classical pursuit of truth to nature and the Baroque pursuit of emotional impact. It shows how deeply Rubens understood antique art while also asserting his own identity as a seventeenth-century painter.

Intellectual and Moral Resonances

For educated viewers in Rubens’ time, Seneca was more than a historical figure; he was a moral authority whose letters and essays circulated widely. Themes such as the control of passion, indifference to fortune, and readiness for death would have resonated in an age marked by political conflict and religious tension.

The rugged, careworn face in Rubens’ portrait encapsulates these ideas visually. This is a man who has seen the world’s brutality yet remains committed to reason. The bare chest and neck, stripped of costume or insignia, portray him as a universal thinker rather than a particular Roman senator. Viewers were invited to see in him an image of philosophical constancy—almost a secular saint of wisdom.

Moreover, Rubens’ own life as a diplomat and court painter, who navigated dangerous political currents while trying to secure peace, may have shaped his interest in Seneca. The artist could recognize in the philosopher a fellow traveler coping with power, responsibility, and moral compromise. The portrait, then, is not only an academic exercise but a personal homage.

Place within Rubens’ Oeuvre

Although Rubens is best known for his colorful canvases filled with muscular bodies and swirling draperies, he also produced—and inspired—numerous prints and drawings. “Bust of Seneca” demonstrates the breadth of his talent, showing that he could work with spare monochrome lines as eloquently as with oil paint.

The study fits within a broader series of classical heads and busts that Rubens examined, sometimes for use in larger compositions. Antique philosophers and heroes appear as models for apostles, prophets, or mythological figures in his paintings. By carefully recording these ancient prototypes, he built a visual library that he could adapt and transform.

At the same time, “Bust of Seneca” stands on its own as an autonomous work of art. It does not clearly relate to a specific narrative painting; instead, it reads as a self-sufficient portrait of a revered intellectual. This autonomy underscores Rubens’ belief that the study of the human head—its forms, expressions, and character—was a worthy subject in itself.

Conclusion

“Bust of Seneca” by Peter Paul Rubens is a small but powerful testimony to the artist’s engagement with antiquity, anatomy, and philosophy. Through disciplined lines and sensitive shading, Rubens transforms a classical bust into a vivid encounter with a thinking, feeling person. The furrowed brow, taut neck, and upward gaze conjure a lifetime of struggle and reflection, making Seneca not just a distant Roman figure but a living interlocutor about the human condition.

In this work we see Rubens as scholar and observer, translating stone into flesh and moral reputation into expression. The portrait invites viewers—then and now—to contemplate endurance, wisdom, and the marks that time and thought leave on the body. It is an image of Stoicism made visible, and an enduring example of how Baroque art could breathe psychological life into the cold marble of the classical past.