Image source: artvee.com

Édouard Manet’s Bullfight (1865) is a visceral and compelling painting that captures the raw energy, cultural ritual, and controversial spectacle of Spanish bullfighting. Painted during Manet’s brief but pivotal trip to Spain, this work represents a moment of stylistic experimentation and emotional engagement. While best known for his urban scenes and groundbreaking contributions to modern art, Manet’s Bullfight reflects a different focus: the drama of movement, the brutality of tradition, and the challenge of capturing motion and narrative in a single visual plane.

This analysis examines the historical context, thematic resonance, composition, painterly technique, and broader significance of Bullfight. As we explore the work in depth, we discover how Manet transformed a culturally specific subject into a universally charged artistic moment—where spectatorship, violence, and art converge.

Historical Context: Manet’s Spanish Sojourn

In 1865, Édouard Manet traveled to Spain, driven by admiration for the Spanish Old Masters—particularly Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya. Manet had already begun his career as a provocateur in the French art world, drawing attention with works like Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) and Olympia (1863), both of which were met with scandal. His trip to Spain marked both a retreat and a reinvigoration, offering him new visual material and a fresh perspective.

While in Spain, Manet became fascinated by bullfighting—a ritual he saw as both brutal and theatrical, tragic and beautiful. Though Bullfight was painted upon his return to France, it was directly inspired by sketches and impressions gathered during this journey. In the arena, Manet found a subject that challenged traditional notions of genre painting and allowed him to merge spectacle with avant-garde technique.

The Scene: Ritual, Chaos, and Spectacle

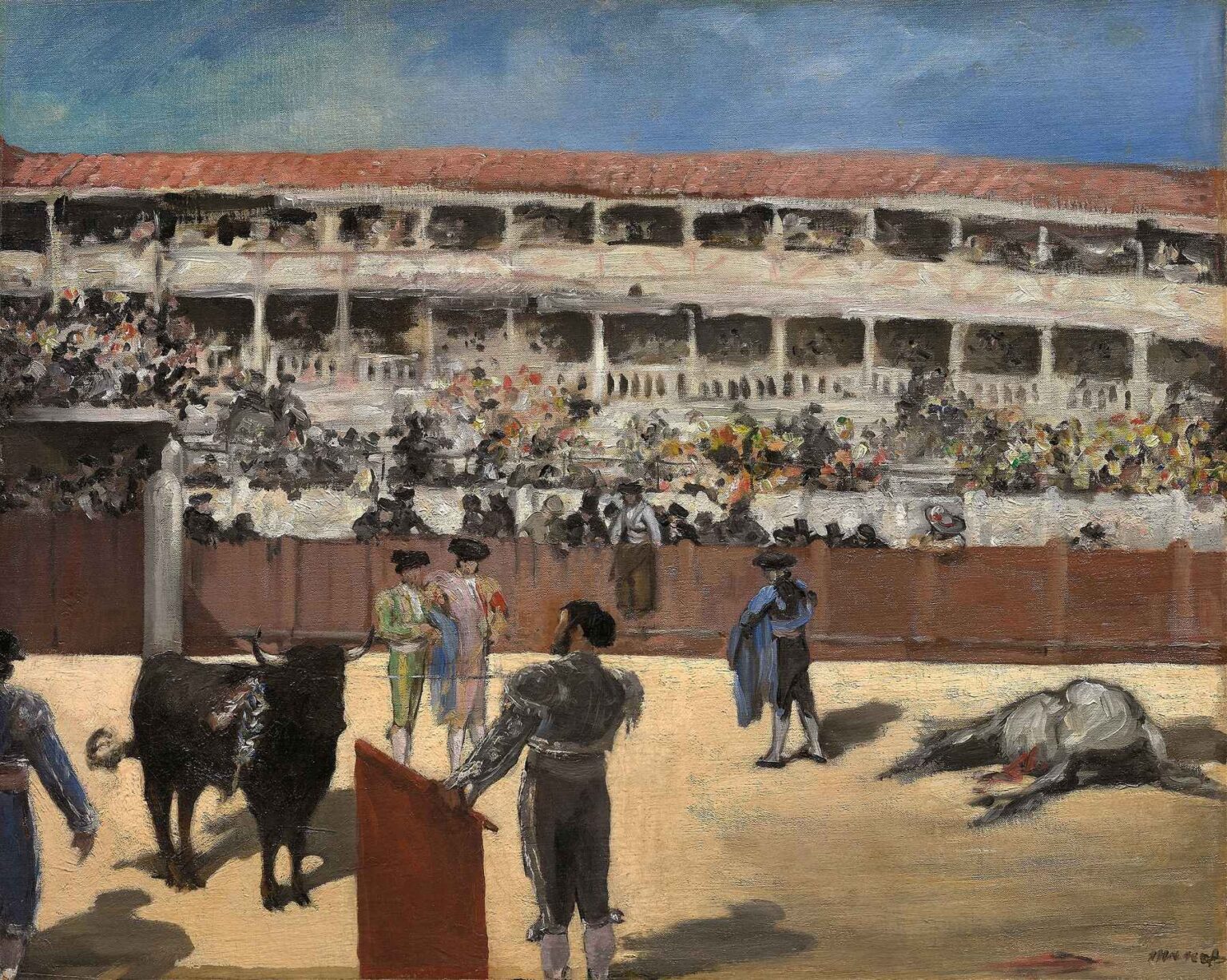

Bullfight depicts a moment of high drama within the bullring. The composition is dense with action: a black bull stands defiantly near center-left, surrounded by several matadors and picadors in colorful costumes. To the right, the bloodied carcass of a horse lies motionless on the sand, a testament to the violence of the preceding minutes. The audience, rendered in blurred strokes, fills the background with indistinct faces and bodies, intensifying the sense of a public spectacle.

This is not a tidy, composed genre scene. Instead, Manet gives us the aftermath of struggle and the anticipation of more. The bull is still standing—its power not yet subdued. The matadors, varied in posture and attire, seem to hesitate, gather, and maneuver. The chaos of movement is matched by the emotional intensity of the subject matter: the tension between life and death, man and animal, performance and destruction.

Bullfighting had long been a favored theme among Romantic artists—most notably Goya—but Manet’s version avoids romanticization. It’s frank, even clinical in its honesty, yet filled with painterly bravado and visual interest.

Composition and Spatial Design

The painting is structured horizontally, dominated by a broad sweep of the arena’s architecture and a low horizon that emphasizes the ground plane. The upper portion is filled with the stands, packed with spectators under a shaded colonnade. This band of whiteness—partially sunlit, partially in shadow—serves as a visual counterpoint to the warmer, blood-stained sand of the foreground.

Manet uses spatial compression to create a sense of immediacy. The middle ground, where most of the action unfolds, is tightly packed with figures. The bull is just slightly off-center, commanding attention. The dead horse on the far right, marked with a red wound, provides a visual anchor and a grim reminder of mortality.

Unlike traditional academic compositions that employ classical perspective, Manet flattens the space. The crowd is rendered as a mosaic of abstract brushwork. The figures of the bullfighters are individualized but not fully modeled, suggesting motion rather than stasis. This compositional strategy evokes Japanese prints—a significant influence on Manet and other modernists—while also challenging the viewer’s expectations for narrative clarity.

Painterly Technique and Brushwork

One of the most remarkable aspects of Bullfight is its bold, almost improvisational brushwork. Manet’s technique here veers toward the proto-Impressionist: he uses quick, loose strokes to capture fleeting impressions rather than detailed realism.

The sand of the arena is rendered with dappled patches of pale ochre and soft gray. The bull’s coat is a rich black with hints of reflective sheen, its form suggested more by contrast than outline. The crowd is composed of tiny flecks of paint—impressions of hats, dresses, and umbrellas rather than defined individuals.

This looseness of technique emphasizes movement, chaos, and spectacle. Manet does not attempt to impose order or narrative certainty. Instead, he invites the viewer into the immediacy of the moment—to feel the heat, tension, and noise of the arena.

It is also worth noting the artist’s economy of means. There is no attempt at over-modeling or excessive detail. Even the dead horse, a focal point of the composition, is treated with stark simplicity: its gray body slumps into the sand, its red wound painted with minimal flourish but undeniable impact.

Color Palette and Emotional Tone

Manet’s color choices in Bullfight are deliberate and expressive. The dominant tones are earthy: ochres, browns, and grays create a foundation of realism and warmth. These are punctuated by moments of brilliance: the bright reds and greens of the bullfighters’ costumes, the deep black of the bull, the cobalt sky above.

The red blood on the sand and the horse introduces a visceral accent—a reminder that this is not merely sport but a life-and-death confrontation. The overall tonality is restrained, even muted in places, which paradoxically amplifies the impact of the bright colors and dramatic elements.

The sky, painted in shades of ultramarine and cerulean, suggests a clear day—beautiful, even serene—set in jarring contrast to the violence below. This juxtaposition intensifies the tension, turning the scene into a layered psychological tableau.

Symbolism and Themes

At its core, Bullfight is about the collision of spectacle and brutality, ritual and reality. The bullring becomes a metaphor for human society: the crowd watches safely behind barriers, while a handful of men and animals face mortal danger.

Several symbolic threads run through the painting:

The bull represents untamed nature, raw power, and animal nobility. Its stance is dignified, not monstrous.

The dead horse signifies sacrifice and the cost of performance. Its body is presented without sentimentality but with solemn weight.

The spectators embody passivity and distance. Their presence reminds us that this is a performance, sanctioned and consumed by society.

Manet does not moralize, but he does present these elements with clarity and detachment. Unlike Goya, whose depictions of bullfights often leaned toward the tragic or grotesque, Manet maintains a journalist’s neutrality—though the placement of the dead horse near the edge of the canvas suggests a quiet commentary on violence and its consequences.

The Role of Spectatorship

One of the painting’s most subtle achievements is its commentary on spectatorship. The crowd in the background, rendered in abstract dabs and flicks, creates a striking contrast with the more defined figures in the foreground. This division reinforces the idea of a divide between viewer and participant, between those who watch and those who risk.

Manet seems to implicate not only the spectators in the stands, but also the viewer of the painting. As we observe the dead horse, the poised bull, the uneasy matadors, we too become part of the spectacle. In this sense, Bullfight anticipates modern art’s interest in the act of viewing—the gaze, its power, and its consequences.

Reception and Legacy

When Manet exhibited his Bullfight works in Paris, they were met with ambivalence. Some critics admired the daring subject and dynamic brushwork, while others decried the painting as crude, unfinished, or morally questionable. Bullfighting was a polarizing subject—seen by some as cultural heritage, by others as barbaric.

Yet the painting’s rawness and refusal to romanticize its subject marked a turning point. Manet was stepping beyond the polished surfaces of salon art into something more immediate, emotional, and modern.

Bullfight was influential for later artists—especially the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists—who admired Manet’s bold color contrasts, flattened forms, and engagement with real life. Pablo Picasso, a devoted fan of bullfighting, would later build on this visual tradition, while artists like Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec would embrace the theater of daily life as valid subject matter.

Manet’s Artistic Philosophy

Bullfight reveals key elements of Manet’s evolving artistic philosophy. He was not interested in idealized narratives or mythological allegory. Instead, he sought to depict life as it is: vibrant, flawed, compelling.

His brushwork, composition, and subject matter in Bullfight show a move toward modernism—away from academic finish and toward immediacy. He was willing to disrupt pictorial conventions to achieve truth. For Manet, painting was not just about representation—it was about confrontation: with tradition, with the viewer, with life.

Conclusion: Violence, Vision, and the Modern Eye

Édouard Manet’s Bullfight (1865) is more than a depiction of a Spanish tradition—it is a layered exploration of spectacle, mortality, and artistic perception. With its raw brushwork, compositional daring, and emotionally charged imagery, the painting bridges Romanticism and Modernism, history and immediacy.

In Bullfight, we see Manet grappling with the contradictions of his time: art versus violence, beauty versus brutality, observer versus participant. He does not resolve these tensions but lays them bare—challenging the viewer to confront their own position.

As a work of modern art, Bullfight remains startlingly relevant. It reminds us that to look is not always to understand, and that the power of painting lies not in clarity, but in the questions it leaves unanswered.