Image source: wikiart.org

A First Look at “Brown Eyes” (1918)

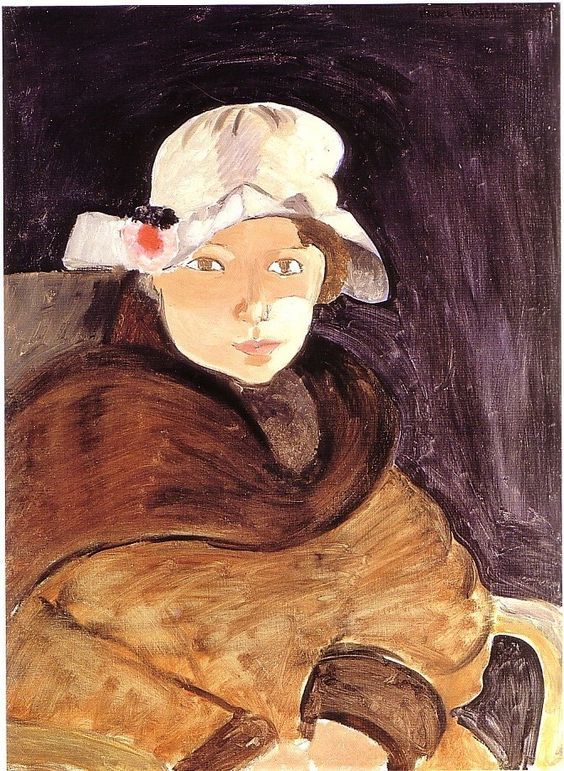

Henri Matisse’s “Brown Eyes” delivers a quiet jolt of presence. A young woman sits close to the picture plane, bundled in a voluminous brown wrap, her face lifted into a steady cone of light. A white hat—soft-brimmed, with a small pink-and-black rosette—frames her features, while a nearly plum-black background deepens the glow of her skin. The composition is simple but calculated: a large field of warm browns, a concentrated island of pale flesh and hat, and a dark surround that holds everything in place. With a handful of tuned colors and a few decisive lines, Matisse builds a portrait that feels intimate, modern, and remarkably calm.

1918: A New Key at the Dawn of the Nice Period

The date of the painting matters. In 1918 Matisse pivoted from the carved, high-contrast canvases of the mid-1910s toward the tempered light and clarity that would define his Nice years. War’s end brought a desire for steadiness, and he found it by editing the world to essentials: shallow, breathable space; large, legible shapes; and color that works by temperature more than saturation. “Brown Eyes” is a compact statement of this new key. The palette is moderated, the modeling spare, and the structure unmistakable. Instead of rhetoric, Matisse offers relation: warm skin against cool white, brown surround against violet-black field, a small flower note that chimes once and then recedes.

Subject, Pose, and the Quiet Charge of Attention

The sitter turns slightly toward us, shoulders wrapped, hands tucked low, head centered under a brim that casts a measured shadow. Her gaze is poised rather than confrontational—curiosity without challenge. There are no props to decode. The chair’s light wooden arm peeks in at the lower right, enough to state scale but not to compete. Everything concentrates on the face and on the enveloping garment. The title focuses our attention on her eyes; Matisse supports that focus by arranging the entire portrait as a funnel: wide brown masses narrow toward the pale oval where those eyes shine.

Composition: Oval, Spiral, and Anchor

The design rests on three moves. First, the oval of the hat and face establishes a firm center. Second, the brown wrap spirals around that center, its sweeping curves creating a soft vortex that guides the eye inward. Third, the deep background acts as an anchor, a dark field that prevents the warm spiral from dissolving. The upper brim tilts forward just enough to set a gentle diagonal; the chair arm and the sitter’s forearms press back with counter curves. The result is a portrait that reads clearly from a distance and rewards slow looking up close.

Palette: Tempered Warmth, Cool Whites, and a Plum-Black Atmosphere

Color carries the mood through temperature rather than shock. The wrap ranges from chestnut to umber to sienna, stroked thinly in places so the ground breathes through. The hat is a milky white touched with faint blue-grays where shadow gathers; its rosette blooms with a single pink petal and a black accent. Flesh notes are peach and pale ocher with a few chilled strokes along the jaw and temple. Behind, the background is a violet-leaning black—dark enough to make the figure glow but warm enough to keep the atmosphere humane. Because everything is tuned rather than saturated, the painting glows from within; warmth sits inside cool, cool inside warm, and the eye registers light more than color names.

Light as Climate, Not Spotlight

Matisse paints light as a stable climate. There is no theatrical beam, no glittering highlight to break the mood. Instead, planes turn with small temperature shifts: a cooler note on the forehead’s far side, a warm pass on the nearer cheek, a gray veil under the brim. The hat’s edge throws a measured shadow across the brow and nose, which Matisse states with two or three confident strokes. Even the bright accent on the lower lip is modest—a quick lift that completes the face’s geometry without announcing itself. The whole portrait sits inside a steady, soft day.

The Brown Wrap: Weight, Rhythm, and Protection

The garment is more than clothing; it is architecture. Broad, sweeping strokes lay its weight across the chest and lap, pooling into darker troughs at the folds. Without becoming fussy, the brushwork gives the wrap a rhythm—undulations that echo the curves of the face and hat. Symbolically, it functions as protection: a warm envelope holding the sitter’s inner light. Structurally, it establishes the major color field (brown) that Matisse balances with the hat’s white and the background’s near-black. As often in the Nice period, fabric becomes a partner to the face rather than a backdrop, doing the compositional heavy lifting so the features can remain simple.

White Hat as Halo and Counterform

The soft white hat does three things at once. It frames the face like a modern halo; it introduces the cool note that the brown field needs; and it carries the portrait’s most assertive edges—crisp here, feathered there—so we feel both cloth and air. The rosette provides a single accent—pink against white with a dark punctuation—that keeps the hat from being merely architectural. Because the brim’s lower edge is drawn with a firm contour over the brow, the hat also clarifies the light direction without resorting to descriptive fuss.

Black as a Positive Color

Matisse’s blacks and near-blacks are never empty; they are pigments in the chord. In “Brown Eyes,” the background absorbs and releases light like a velvet curtain; the rosette carries a dot of deep black that locks the hat into the palette; thin, dark accents at the eyes, under the nose, and along the mouth make the features ring without resorting to outline. Against warm browns and milky whites, those blacks stabilize the harmony like a bass note in a string quartet.

Brushwork and the Visible Pace of Making

The surface reveals its making. Long, loaded strokes describe the wrap’s curves; shorter, adjusted passes turn the cheek; quick, concise touches establish the eyes and the tiny flare of nostrils. On the background, Matisse drags the brush so slightly different purples and blacks knit together into a breathable field. He avoids cosmetic blending; zones meet cleanly and keep their individual tempos. That variety of tempo—slow in the garment, quicker in the features, steady in the background—keeps the portrait alive without forfeiting calm.

Space Held Close to the Plane

Depth is felt but shallow. Overlaps do the work: hat before background, face inside the hat, wrap over lap. There is no vanishing-point architecture and no cast shadow that would tie the sitter to a specific corner of a room. Instead, Matisse’s shallow space lets the image function as both likeness and designed surface. It fits his Nice-period conviction that serenity is easier to build when a painting acknowledges its flatness.

Edges, Seams, and the Craft of Meeting

One of the portrait’s pleasures is how edges behave. Where the hat meets the background, the seam alternates between crisp and breathed—exact where the brim turns toward us, softened where cloth turns away. Where the wrap crosses the chest, a thin, lighter line—sometimes simply the tooth of the ground—separates adjacent folds so they don’t collapse into one mass. Where skin meets the brim’s shadow, a faint halo appears, a by-product of painting wet-over-wet that Matisse allows to remain because it reads as air. These tailored joins keep simplified forms from looking cut out and help the sitter inhabit the space.

The Eyes: Title and Fulcrum

The painting’s title directs attention to the eyes, and Matisse responds with restraint. Each eye is set with a small, dark almond that thickens toward the lid’s outer edge. Pupils are indicated by a dark dot or short stroke, enough to focus the gaze without freezing it. A lighter touch beneath each eye suggests reflected light from the wrap and keeps the stare alive. Because the rest of the face is so economical, these few marks carry tremendous weight. They give the portrait its quiet charge—the sense that a mind is present behind the calm.

Comparisons Within the 1918 Constellation

Set “Brown Eyes” beside Matisse’s other 1918 portraits and its role clarifies. Compared with the frontal, icon-like “Woman with Dark Hair,” it is softer and more enveloped. Compared with the more ornate “Marguerite with a Leather Hat,” it is austerer, swapping ornamental blues and oranges for a limited brown-white-black chord. Compared with the airy balcony scenes of the same year, the background tightens here into close, velvety space. Together these works chart the vocabulary Matisse would elaborate through the 1920s: tuned temperatures, living blacks, shallow stage, and forms simplified to their expressive core.

Dialogues with Tradition

The portrait speaks quietly with several traditions. The frontal head against a dark ground recalls early Italian panels; the soft white hat, with its flower, nods to modern fashion portraiture; the calligraphic accents at the features owe something to Japanese prints Matisse revered; and the planar construction of the face continues Cézanne’s lesson that volume can be built with neighboring color planes rather than blended chiaroscuro. By absorbing these lessons and stripping them to essentials, Matisse achieves a likeness that is at once classical and unmistakably modern.

Ethics of Calm and Privacy

Matisse often said he wanted his paintings to offer “balance, purity, and serenity.” In a portrait, those aims come with an ethical dimension. The sitter of “Brown Eyes” is not turned into narrative or spectacle; her dress is modest, her pose reserved, her gaze steady. We are invited to share her climate rather than to pry into her story. That privacy, combined with the sensuous presence of paint, is a key reason the picture feels restful rather than inert.

How to Look: A Guided Circuit

Enter at the lower right where the wrap rounds the arm and pushes against the chair’s light wood. Follow the sweep upward to the broad collar of brown that arcs around the throat. Let your eye pass beneath the brim’s shadow to the nose’s quick plane change and the small, bright note on the lower lip. Step up into the white hat and trace its scalloped edge, then slide left to the pink-and-black rosette and register how it locks the cool hat to the warm wrap. Drop back through the dark background, noticing its slow, purplish undulations, and return to the eyes, which now feel like the fulcrum of the whole. Repeat the loop; the painting’s rhythm becomes a calm breath.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Look closely and you’ll see pentimenti—the history of decision. A brim restated with a cooler pass, a shoulder line adjusted and then secured by a darker fold, a highlight on the lip added late to finish the face’s geometry. Matisse does not polish these traces away. He stops when relations are inevitable, not when surfaces are cosmetically even. That earned inevitability—the feeling that nothing more is needed—is the portrait’s deepest sophistication.

Why “Brown Eyes” Still Feels Contemporary

A century on, the painting remains fresh because its clarity aligns with how we see now. Big shapes read instantly; the palette is sophisticated rather than loud; process is visible and honest; space stays close to the plane in a way that suits photographic and graphic sensibilities. Most of all, the portrait trusts a small set of true relations—brown wrap, white hat, plum-black air, and two measured eyes—to carry human presence. That trust is as modern today as it was in 1918.

Conclusion: Presence Built from Essentials

“Brown Eyes” is a masterclass in reduction without loss. With a narrow range of colors, the authority of black, and the orchestration of a few edges, Matisse brings us into quiet company with a living person. The hat acts as halo and counterform; the wrap creates weight and rhythm; the background steadies the chord; and the eyes—compact, exact—hold the gaze with humane reserve. It is an image you don’t get over quickly because it shows how little is required, when placed exactly, to make presence tangible. The portrait stands as an early Nice-period touchstone: serenity achieved through structure, intimacy through restraint, and feeling carried by color and line rather than by anecdote.