Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions

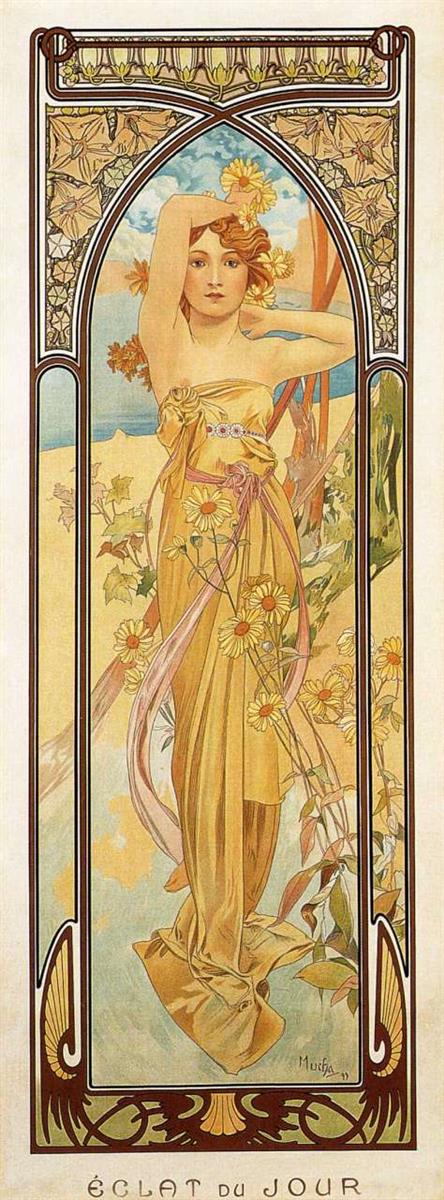

“Brightness of Day” (1899) greets the eye like a sunlit window. A slender young woman stands within a tall, pointed arch, her body swathed in shimmering gold, her arms lifted to gather her hair. Daisies cluster at her waist and trail along airy ribbons. Behind her, a pale sky and calm water open the scene, while ivy and stylized ornaments wrap the frame. The entire composition rises like a column of light, converting the everyday sensation of midday radiance into a serene allegory. It is quintessential Mucha: a union of figure, flower, ornament, and letterforms orchestrated into a single, convincing mood.

Historical Moment

The year 1899 marks the height of Alphonse Mucha’s Parisian renown. After the explosive success of his theater posters in the mid-1890s, he devoted increasing energy to decorative panels—affordable color lithographs meant to bring art into private interiors. These panels distilled ideas into personifications: seasons, gemstones, arts, and times of day. “Brightness of Day,” titled in French at the foot as “ÉCLAT du JOUR,” belongs to this flowering of domestic art. It translates the promise of modern living—electric light, open boulevards, fashionable apartments—into a classical language of harmony and grace.

Place Within A Series

“Brightness of Day” is one of Mucha’s meditations on the cycle of hours. Where other panels in the grouping explore the hush of morning or the languor of night, this image embodies the noon hour’s clarity. The figure’s golden dress and crown of daisies summarize daylight without resorting to narrative. Rather than depict the sun itself, Mucha personifies its effect: lucidity, warmth, alertness. The series logic matters, because it governs choices of color, gesture, and plant motifs that together define a distinct time of day within a consistent visual grammar.

Composition And Framing

The panel is a tall rectangle with a Gothic-inspired arch nested within it. The arch does more than decorate; it stabilizes the composition and focuses attention. Its pointed apex guides the gaze upward to the model’s raised arms and auburn hair, while its dark linear outline keeps the pale landscape from bleeding into the margins. Mucha divides the rectangle into zones: an ornamental cornice with ivy and roundels at the top, the main field with the figure and landscape, and a base with stylized shells and the inscription. This architectural staging converts the fleeting phenomenon of daylight into something enduring and ceremonial.

The Figure And Gesture

The woman stands contrapposto, her weight settled, her hips subtly angled, the long sheath of cloth pooling at her feet. One arm reaches behind the head, gathering hair, while the other softens the pose with a gentle countercurve. The facial expression is calm and alert—not dreamy, not theatrical. Mucha’s women often embody interior states; here the state is wakefulness. The lifted arms create horizontals that play against the panel’s dominant vertical, just as midday balances ascent and steadiness. Ribbons slip from her hair and waist like loose sunbeams caught by a breeze, their movement animating the stillness.

Flora And Symbolism

Daisies are the principal botanical motif, tucked at the bodice, cinched at the belt, and scattered among trailing stems. As emblems, daisies suggest daylight, innocence, and unpretentious joy. Their simple radiating petals echo the idea of sun rays, and their yellow-white coloration harmonizes with the palette of noon. Ivy crowns the upper border, connoting constancy and the evergreen vitality of natural cycles. Together the plants communicate the character of the hour: clear, faithful, uncomplicated. Mucha’s floral symbolism is never cryptic for its own sake; it functions as legible poetry that anyone can read at a glance.

Color And Light

Color carries the theme. The dress and ribbons glow in saffron and honey, tempered by subtle violets in the shadows. The background breathes pale blues and creams, an atmosphere washed by high daylight. Greens in the ivy and leaves provide cool relief, preventing the gold from becoming monotonous. Mucha rarely uses extreme contrast; instead he stacks harmonious intervals—gold into ochre, blue into aqua—creating the sensation of even illumination. The result is a print that seems to emit light rather than simply reflect it.

Line And Ornament

Dark brown line is the skeleton of the image. It defines the arch, draws leaf veins, traces folds of cloth, and articulates hair. Mucha’s line is elastic: tense where structure is needed, loose where motion is suggested. The famous Art Nouveau “whiplash” curve is present in the ribbons and stems, yet it never unmoors the design. Everything flows toward equilibrium. The ornamental panels at top and bottom are not afterthoughts; their geometry—little roundels, diagonal knots, and shell-like palmettes—locks the free organic lines into a disciplined frame, just as daytime organizes the world into clarity.

Space And Background

Unlike his theatrical posters that press figures against shallow grounds, Mucha opens this panel to a modest landscape. A sandy bank, a light surf, and a clear horizon place the figure near water, a classic setting for the freshness of day. The landscape is not descriptive in the naturalistic sense; it is an atmosphere, a breath of distance. The arch prevents this space from destabilizing the design, turning the view into a framed vista. The effect is both expansive and contained: day opens the world, but the composition keeps it articulate.

Typography And Inscription

At the base, the inscription “ÉCLAT du JOUR” appears in delicately modeled capitals. The letters are upright and lucid, echoing the hour they name. Mucha integrates text as living ornament; the inscription is weighted to balance the upper cornice and sized to support the figure without competing with it. The kerning and rhythm of the words feel architectural, like the carving on a lintel. Text and image belong to one breath.

Lithographic Craft

The panel is a color lithograph, printed from multiple stones, each carrying one color laid in careful register. Mucha designs with the process in mind: broad fields of even tone, cleanly bounded by line, allow for rich color without muddiness; translucent passages overprint to create secondary hues; delicate hatching inside the flowers and sash yields soft modulation. The printing imparts a velvety surface and a quiet saturation suited to the calm theme. Lithography also situates the artwork within the realm of modern reproduction, aligning it with the promise of daylight that banishes the murk of premodern interiors.

The Dress As Architecture Of Light

The garment is central to the allegory. It is not merely clothing but a column of gold—a fabric architecture that captures and funnels brightness. The bodice gathers like a sunburst, its folds radiating outward from a central clasp. Down the skirt, long vertical flutes echo classical columns, while the hem pools like a small wave of molten metal. By staging light as cloth, Mucha reveals his root insight: sunlight in a decorative panel is best expressed through surface, sheen, and contour, not through cast shadows or dazzling highlights.

Gesture Of The Arms

Raised arms are common in Mucha’s panels, but here the gesture has special force. At midday the sun is overhead; the lifted arms mirror that orientation. They also open the chest, creating a posture of reception. The figure is not shielding her eyes or reaching toward something she lacks; she is arranging herself for composure in full light. The gesture asserts mastery of the hour rather than submission to it. In this way, the allegory proposes a human analog to daylight: clarity as a chosen stance.

Rhythm And Movement

Despite its serenity, the image moves. Ribbons trace slow arcs; stems climb at diagonals; the dress drops in measured cascades. Mucha composes rhythm like a musician, alternating long lines with short accents. The daisies punctuate the golden field like bright notes. Even the ivy scrolls in a counter-rhythm to the vertical frame. This orchestration converts static decoration into living pattern, so that the viewer’s gaze travels rather than stalls.

Comparison Within Mucha’s Day-Cycle

When compared with the companion hours, “Brightness of Day” is the most upright and direct. Morning images tend to contain misty softness and awakening gestures; evening invites languor and lower chroma; night withdraws into crescent forms and cool blues. Day stands squarely in the middle of the register. The palette here is warm but not fevered, the pose alert but not tense, the ornament abundant but not extravagant. The panel is the keystone of the cycle—the hour when everything is most itself.

Allegory Without Narrative

One of Mucha’s enduring achievements is his ability to express complex ideas without anecdote. There is no literal sun, no clock, no specific story. Day is present through inference: color, pose, botany, and framing combine as a set of signs. This economy respects the viewer’s intelligence and keeps the image timeless. In avoiding anecdote, Mucha secures universality; the panel can hang in any room, in any year, and still mean daylight.

The Human Face As Locus Of Theme

The model’s face is attentive. Eyes look forward with calm brightness; lips rest in an unreadable half-smile. The face asserts the hour’s psychology: wakefulness, composure, benevolence. Mucha paints faces with minimal modeling in his lithographs, relying on gentle tonal transitions and precise contour. Here that restraint keeps the countenance luminous. The absence of strong cast shadows is deliberate; midday light, high and diffused, softens edges and democratizes surfaces. The face becomes a small sun of consciousness at the center of the composition.

Decorative Ethics And Domestic Life

These panels were designed for living rooms, bedrooms, and foyers. “Brightness of Day” proposes an ethos for domestic life: order infused with grace. The tall format suits narrow wall spaces, turning architectural voids into sources of visual light. The work suggests that beauty is not an occasional spectacle but a daily companion. In this sense, the panel is both ornament and counsel, a gentle instruction to hold oneself in the posture of clarity that the hour invites.

Interplay Of Nature And Architecture

Mucha fuses natural forms with architectural discipline. Ivy and daisies thrive within a frame built of arches, roundels, and palmettes. The strategy rescues ornament from mere repetition and rescues nature from formlessness. The viewer senses that nature is at home within culture and that culture is ennobled by nature. This reconciliation is a cornerstone of Mucha’s style and one reason his panels feel perpetually fresh.

Legacy And Reception

While the popular imagination associates Mucha most strongly with posters of actresses and perfumes, panels like “Brightness of Day” reveal the lasting core of his vision. They outlived the ephemera of commerce because they operated as instruments of atmosphere rather than announcements. Collectors could live with them, day in and day out, and continue to draw pleasure from their equilibrium. In “Brightness of Day,” the equilibrium is perfectly judged: an image that radiates optimism without noise.

Conclusion

“Brightness of Day” is an anthem to clarity. Through a poised figure, a disciplined frame, and a palette tuned to the color of noon, Alphonse Mucha converts a transient hour into a durable emblem. Daisies declare the simplicity of daylight; ribbons and stems carry the music of warm air; the arch holds everything in lucid order. The panel exemplifies what made Mucha indispensable to modern decorative art: his ability to harmonize the organic and the geometric, the sensual and the serene, until a room feels brighter simply because his work is in it.