Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Quiet Gesture Set Ablaze by Color

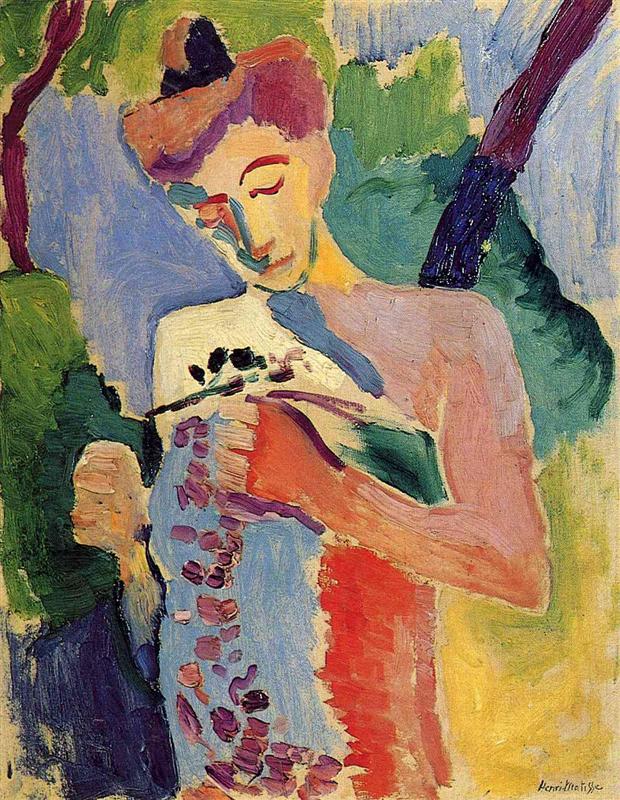

“Branch Of Flowers” (1906) greets the eye with a figure who bends slightly inward, intent on a small spray of blossoms held at chest height. The moment is almost domestic in its simplicity, yet the painting turns the private gesture into a chromatic event. Blocks of cool lavender, turquoise, and leafy green push against ripe coral, rose, and butter yellow; the whole surface vibrates with Fauvist conviction that color is not a skin laid on reality but a way of building it. Matisse streamlines forms into generous planes and accents their junctures with assertive seams, creating a portrait that is both tender and structurally bold.

1906 Context: From Fauvist Shock to Constructive Poise

Painted in the year after the Fauves scandalized Paris with pure, unmodulated pigment, this canvas belongs to Matisse’s period of consolidation. The fever of 1905 has not cooled so much as deepened. Color remains high-key, but it is organized into a calm armature of verticals and diagonals; the drawing is resolute, the intervals between hues deliberately spaced. Rather than chasing intensity for its own sake, Matisse is now testing how color alone can articulate figure, space, and mood. The subject—an absorbed woman examining a twig—embodies this interior turn: attention becomes the drama.

Composition: Triangles, Hinges, and a Picture that Breathes

The composition reads as a large, stabilizing triangle whose base runs along the lower edge and whose apex rises near the figure’s topknot. Inside this triangle, two hinges animate the surface. The first hinge is the diagonal of the right forearm angling upward to the branch; the second is the slope from the left shoulder down the torso, a counter-diagonal that prevents symmetry from settling into inertia. Flanking green masses work like arboreal wings—leafy shapes that nudge the figure forward while echoing the plant she holds. At the lower left, a smaller, blocky shape—part profile, part color-study—acts as a ballast, keeping the eye from drifting out of the picture while reinforcing the vertical cadence.

The Architecture of Color: Warm Body, Cool Air

Matisse builds the image with temperature zones. The figure’s skin is mapped by peach, apricot, and rose, while the surrounding air chills to periwinkle and mint. These temperatures aren’t arbitrary; they lock form together. A cool, slate-blue band cuts down the sternum to model the chest; pale lemon at the neck warms toward the head, implying circulation rather than a theatrical spotlight. The dress or draped cloth—lavender flecked with mauve—becomes a transitional field between the warm body and cool background. Green appears twice, with two distinct functions: as deep, leafy masses that suggest foliage and as a firmer, emerald wedge at the figure’s ribs that acts like an internal brace, keeping the torso upright within the frame.

Drawing With Color Instead of Contour

Look at how few literal outlines there are. The jaw appears where a strip of green cools against the cheek’s orange; the nose is a single decisive stroke that turns from brow to nostril; the eyelids are not filigree but brief, calligraphic marks set into the plane of the face. The hand is simplified into a compact, angled unit whose silhouette is made by the collision of coral and lavender. Edges are therefore not fences but seams. They breathe, opening and tightening as temperatures change, so that the figure feels grown out of the same substance as its surroundings.

Gesture and Attention: Meaning Through Posture

The painting’s subject is concentration. There is no ornament or anecdote beyond what the body does with the branch. The inclined head, the closed or half-lidded eye, the slight containment of the shoulders—these add up to an ethics of looking. Matisse dignifies ordinary attention by giving it the full resources of modern color and composition. The branch itself is modest: a handful of dark leaves capped by tiny blooms. Precisely because it is modest, it anchors the scene, the way a single low note steadies a musical phrase. The viewer is invited to look as the sitter looks—closely, patiently, without narrative hurry.

Brushwork and Surface: Tactile Planes That Turn With the Form

The paint is laid with confidence. In the sky-like field to the left, long, even strokes run vertically, their visible ridges catching light and keeping that zone open and airy. Across the face and torso, shorter, square-ended strokes stack like shingles—a Cézannian inheritance adapted to Matisse’s broader chromatic planes—so that form turns by increments rather than blended gradients. The dark leaves on the twig are quick daubs, thick enough to stand up from the violet ground. Everywhere touch is adjusted to substance: smooth where the eye should rest; impastoed where detail matters.

Light Without Chiaroscuro

Illumination here is a logic of relations rather than a narrative of sunlight. The face glows not because it sits under a beam, but because Matisse calibrates surrounding hues to make it advance: a cool periwinkle halo at left, a green wedge at right, and the pale citron at the neck that slips gently into the warm cheek. Shadows are not brown; they are tempered versions of neighboring colors—slate blues and olive greens—that close form without muddying it. This method keeps the canvas lucid. The viewer reads volume instantly but never feels bullied by stagecraft.

Space by Overlap, Pressure, and Breath

Depth is shallow yet convincing. The green masses overlap the figure at shoulder height, pushing the body forward. A pale yellow field at right relieves that pressure and grants breath. The lower-left block shape sits in front of the periwinkle wall but behind the figure, a small but crucial signal that space is layered, not merely patterned. The result is a room that behaves like weather. Air has temperature and direction; it presses and releases rather than simply surrounding.

Pattern, Ornament, and Restraint

The violet garment spattered with mauve dabs introduces the picture’s only overt pattern. Even here, Matisse keeps decoration purposeful. The dabs are scaled to the fingers that pinch the fabric, so that pattern becomes a register of touch. They also echo the little blossoms on the branch—motif outside, motif on the body—binding human and natural realms. Elsewhere he resists ornament. The background is all planes; the hair is a single dark cap. This restraint gives the small patterned zone greater authority and prevents the image from slipping into mere prettiness.

The Role of Dark Accents

Fauvist color gains stability from its sparing use of dark. In this canvas, black and near-black appear in the leaf cluster, along the nose’s inner edge, in the line that defines the eyelids, and at the hair knot. Each accent is a rivet. The eye latches onto them, and the surrounding high-key colors lock into place. Take away those small depths and the painting would float. With them, it sits.

Psychological Reading: Serenity Inward, Energy Outward

The face broadcasts calm. The lowered gaze and softened mouth suggest unguarded attention rather than display. Meanwhile, everything around the face hums with energy. Angular green shapes lean in; periwinkle strokes climb; the red wedge of the torso presses forward. The painting thus turns inside-out: quiet at the core, vigorous at the edges. Matisse often engineers this paradox, letting the body be a zone of stillness while the world around it flickers and stirs. The effect is humane. Serenity is not passivity; it is poise amid movement.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s 1906 Work

Placed next to the fiercer “Gypsy” or the rugged “Self-Portrait in a Striped T-Shirt,” “Branch Of Flowers” tilts toward lyricism. Its chroma is no less bold, yet the sequencing of hues is softer, and the drawing favors gently turning planes rather than chiselled facets. It also anticipates the decorative unity of later interiors: a figure integrated with surrounding fields rather than set apart from them. The simplified hands and the patterned cloth point forward to the great studio scenes in which textiles, foliage, and bodies cohabit a single ornamental order.

Influences: Cézanne’s Construction and Gauguin’s License, Transformed

The firm, blocky method that turns the torso owes something to Cézanne’s constructive stroke—the idea that volume can be assembled from flat touches laid with direction and purpose. The chromatic license that lets green and blue wander across flesh recalls Gauguin’s synthetism. But Matisse changes their stakes. With Cézanne, the brushwork can feel analytic; with Matisse it feels generous, relaxed, confident. With Gauguin, color often symbolized; with Matisse it persuades by pleasure and clarity rather than by code.

Edge Behavior: Where Figure Meets World

Edges shift character as needed. The cheek meets periwinkle in a soft dissolve, so the head seems bathed in cool air. The forearm’s coral cuts sharply against lavender, letting the hand bite down on the cloth. The emerald wedge at the ribs is crisp at its top edge and softer at its bottom, a nuanced decision that keeps the torso turning without losing firmness. Under the chin, a cool band slips between head and shoulder like a breeze, separating the two volumes without resorting to a heavy line. Such edge variations keep the surface alive and direct the viewer’s attention from emphasis to emphasis.

The Branch Itself: Small, Dark, Central

Why does a tiny twig hold the center of the painting? Because Matisse makes it the densest concentration of value and the crispest instance of drawing. The leaves are deep and compact; the blossoms are small flecks of light; the shaft is a taut line that echoes the forearm. This concentrated event reads as the painting’s heart. It gives the figure something to do, the eye somewhere to land, and the composition a pivot about which color planes turn.

Material Presence and the Time of Making

The canvas does not conceal its process. You can see under-layers of warmer ground peeking through cool passages and vice versa, proof that the image was tuned through successive decisions rather than plotted in advance. That visibility of making is part of the picture’s appeal. It invites the viewer to occupy the same time as the painter, to feel how a cheek was placed against a field, how a shoulder was sharpened at the last moment with a cooler stroke. The sitter’s quiet concentration finds its analogue in the painter’s attentive touch.

Meaning Without Allegory

No story is told and none is needed. The painting proposes that looking closely at a small thing—its weight, its pattern, its coolness against the palm—can reorganize the world. That proposition is embodied in every relation on the surface: warm to cool, near to far, dense to open. The figure’s tenderness toward the branch becomes Matisse’s tenderness toward painting’s own means. In “Branch Of Flowers,” attention is not simply represented; it is enacted in how the picture is built.

Lasting Significance: A Grammar of Calm Radiance

This work distills a grammar that Matisse would extend for decades: large, well-spaced color planes; sparing darks; edges that alternate between seam and dissolve; pattern used as structural rhyme; human presence conceived as a zone of poise within a lively decorative order. The result is a calm radiance that never dulls. You leave the painting with a sharpened sense of color’s capacity to carry feeling without noise and of form’s ability to breathe within a flat rectangle.