Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context and Munch’s Artistic Evolution

In 1899, when Edvard Munch created “Boys Bathing,” he was moving beyond the anguished symbolism of his earlier Scream series and exploring more intimate human experiences. At thirty-five years old, Munch had already spent a decade challenging naturalism, infusing figural scenes with expressive color and form. Having settled in Berlin in the late 1890s, he encountered both academic and avant-garde currents, absorbing lessons from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism while retaining his personal emphasis on inner feeling. “Boys Bathing” belongs to a group of works in which Munch turned to moments of youthful ritual and vulnerability, using everyday activities as vehicles for exploring communal bonds, erotic undertones, and the fleeting nature of innocence. Within the broader context of fin-de-siècle Europe—marked by rapid urbanization and shifting social mores—Munch’s focus on adolescence and nature can be seen as both a retreat from modern pressures and a probing of emerging identities.

Subject Matter and Imagery

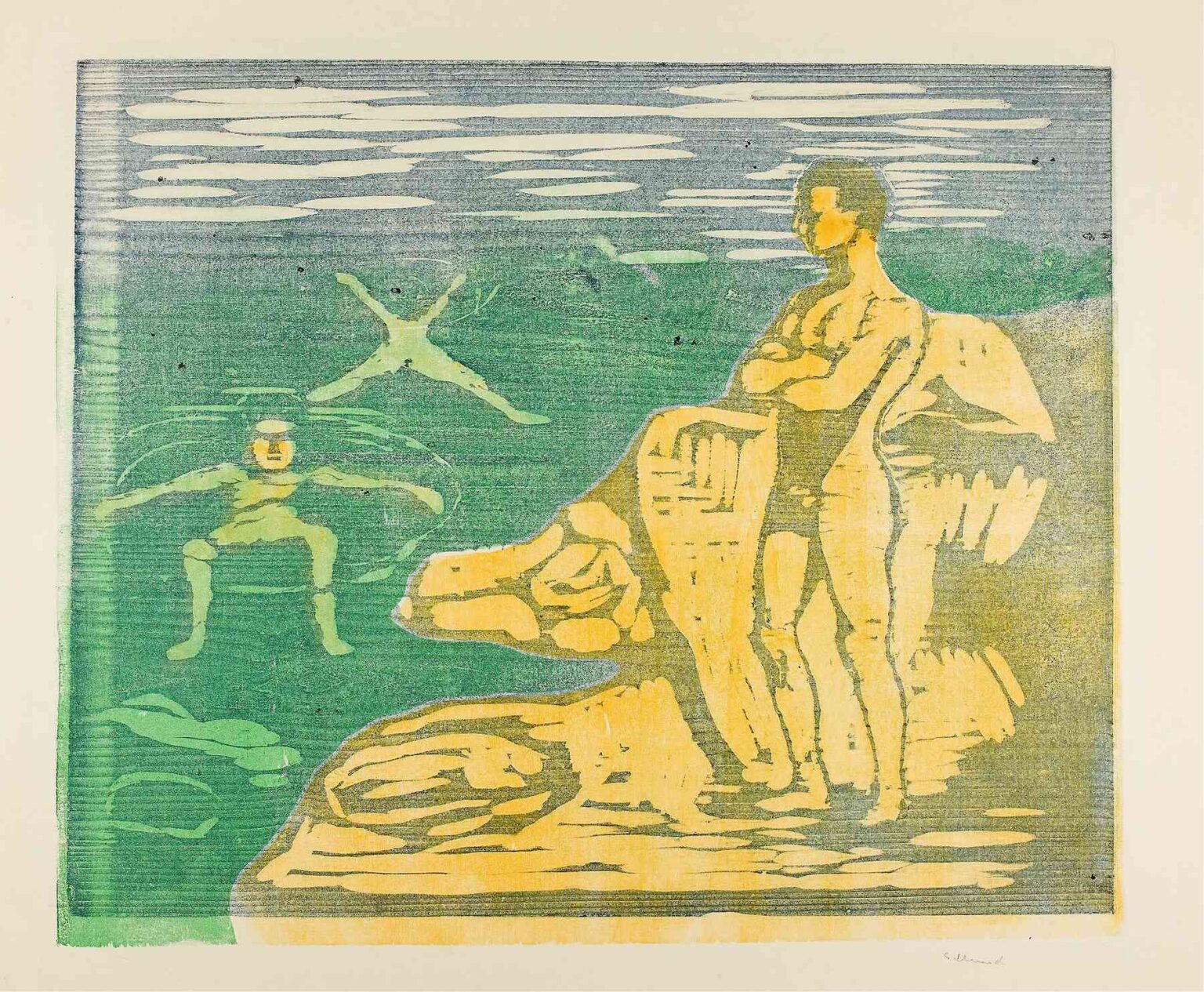

At first glance, “Boys Bathing” depicts three nude youths at the water’s edge: two are immersed in the green-tinted shallows, their bodies partly submerged, while the third stands on a rocky outcrop, arms folded, gazing toward the horizon. Their figures are simplified, with neither facial detail nor musculature emphasized; instead, Munch builds them from broad, flat areas of pale yellow and ochre. The water is a swirl of vert and emerald, punctuated by the skimming trails of ripples, and the sky above dissolves into horizontal bands of silvery gray. This minimalism invites reflection: the youths could be playing, communing, or contemplating. The scene transcends a mere genre painting to become a carefully orchestrated tableau in which human forms and natural elements interlock to evoke both physical presence and emotional resonance.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Munch arranges “Boys Bathing” in a horizontal format that accentuates the expansiveness of the natural setting. The standing figure occupies the right third of the canvas, establishing a vertical counterpoint to the horizontal bands of water and sky. The two swimmers, positioned at different depths, create a diagonal axis that leads the eye from the rock’s edge into the aquatic realm. Munch omits any distant shoreline or background detail, compressing space so that the sky, water, and rocky ledge bleed into one another. This compositional flattening reinforces the sense that the scene unfolds in a liminal zone—neither fully terrestrial nor completely aquatic. Without perspective cues, the viewer is invited to focus on the interplay of shapes and colors, and on the psychologically charged stillness that binds the figures and environment together.

Color Palette and Emotional Resonance

In “Boys Bathing,” Munch’s palette is at once restrained and evocative. The water glows in a range of greens—from pale mint to deep forest—achieved through successive layers of woodcut inks and printed tints. The youths’ bodies are rendered in warm ochres and muted yellows, their intensity heightened by the cool tones that envelop them. The rocky outcrop recalls sunlit sand, its golds and tans echoing the figures while contrasting with the watery greens. The sky is a subtle silver gray with lavender undertones, imparting a subdued, twilight-like atmosphere. These deliberate color relationships generate emotional tension: the warm bodies appear almost vulnerable amid the cool, enveloping water, suggesting themes of initiation, exposure, and the passage from childhood into a more uncertain adulthood.

Brushwork and Printmaking Technique

Unlike his easel paintings, “Boys Bathing” is a color woodcut—a medium Munch championed as a means of integrating drawing, painting, and relief printing. He carved multiple blocks, one for each major hue, and printed them in succession, allowing areas of ink to overlap and interact unpredictably. The result is a textured surface enlivened by the woodcut’s grain and the occasional register variance between blocks. Horizontal striations in the sky and water speak to the wood’s natural lines, while the figures and rock are defined by more solid, unbroken color planes. Munch’s woodcut technique yields an organic vitality, as if the scene were emerging from the wood itself. The democratic reproducibility of prints also speaks to Munch’s desire to disseminate his work more widely, breaking from the exclusivity of single canvases.

Light, Atmosphere, and Mood

Munch does not anchor “Boys Bathing” to a specific time of day; instead, he evokes a timeless, almost mythic ambiance. The absence of cast shadows and the uniform illumination suggest a diffuse light—perhaps early dawn or late dusk—when colors mellow and forms blur. The standing youth’s silhouette is backlit by the pale sky, creating a subtle halo effect that isolates him as a contemplative guardian or guide. The water’s surface registers only soft highlights, as if the sun were behind clouds. This atmospheric subtlety reinforces a feeling of stillness and introspection. The scene seems suspended between motion and rest: we sense the previous play of the swimmers and anticipate their next move, yet the overall mood remains quietly expectant.

Symbolism and Thematic Depth

While on the surface “Boys Bathing” captures a simple summer ritual, Munch infuses the scene with symbolic resonance. Water has long served as a metaphor for the unconscious, and the act of bathing implies cleansing, transformation, and rebirth. The trio of figures can be read as stages of transition: the swimmers fully immersed in the water, the athlete on the verge of entry or exit, and the exposed youth surveying the unknown. This echoes Munch’s broader interest in life’s thresholds—childhood to adulthood, health to illness, life to death. The rocky perch may symbolize the solidity of self, while the enveloping water represents emotional currents beyond conscious control. In this light, the print becomes an allegory of personal growth and the vulnerability inherent in any rite of passage.

Psychological Interpretations

Munch’s fascination with the inner life finds expression in “Boys Bathing” through the juxtaposition of communal play and solitary contemplation. The two swimmers may suggest shared youthfulness and exuberance, but the standing figure’s folded arms and distant gaze introduce introspection and emotional distance. This ambivalence—between togetherness and isolation—is a hallmark of Munch’s psychological portraiture. One might read the scene as a meditation on adolescence’s tensions: the thrill of communal freedom tempered by the dawning awareness of existential separateness. In psychoanalytic terms, the water embodies the unconscious, and the youths’ varying degrees of immersion reflect differing capacities to engage with inner realities. This subtle layering of feeling resonates with Munch’s view of painting as a means to externalize the psyche.

Relation to Munch’s Other Works

“Boys Bathing” sits alongside Munch’s other late-1890s explorations of youth and nature, such as “Puberty” (1894–95) and “Ashes” (1894). While those paintings emphasize darker emotional states—anxiety, erotic melancholy—“Boys Bathing” is comparatively serene yet no less profound. In contrast to his tormented urban portraits, Munch here returns to outdoor ritual and communal innocence, albeit shadowed by his signature introspection. The print also anticipates his later Frieze of Life series’ themes, in which water, bathing, and naked bodies recur as symbols of vulnerability and renewal. Technically, “Boys Bathing” exemplifies Munch’s woodcut experiments in layering color—an approach he would refine into some of the most innovative color prints of the early twentieth century.

Technical Aspects and Conservation

Color woodcuts require exacting registration of multiple blocks, and Munch often left deliberate mis-alignments to enhance expressiveness. In “Boys Bathing,” slight overlaps of green and ochre create rich secondary tones, while the grain of the woodblock contributes natural irregularities. Conservation studies reveal that Munch printed on lightweight Japanese paper, affording translucency but also vulnerability to handling. The print’s pigments—aniline dyes and oil-based inks—have remained remarkably stable, though minor fading in the palest sky areas is visible. The paper shows typical age discoloration along margins, carefully addressed in modern conservation framing. Infrared reflectography of the blocks shows Munch’s handwritten registration marks, underscoring his hands-on approach to printmaking.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After Munch’s death in 1944, his widow bequeathed many prints to Norwegian institutions. “Boys Bathing” entered the collection of the Munch Museum in Oslo in the late 1940s, where it became a staple of exhibitions on Munch’s printmaking. The work traveled internationally in retrospectives during the 1980s and 1990s, showcasing Munch’s contributions to graphic arts. Its inclusion in catalogs raisonné of Munch’s prints has cemented its status as a key example of his late-nineteenth-century woodcut practice. Private collectors also prize early impressions of the print, and auction records from the 2000s reflect its significant market value among Munch’s color prints.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Early twentieth-century critics regarded Munch’s color woodcuts with mixed enthusiasm, often favoring his easel paintings. By mid-century, scholars recognized the prints’ technical innovation and emotional intensity. “Boys Bathing” in particular has been celebrated for its harmonious synthesis of form, color, and psychological depth. Contemporary critics praise the work’s prescient minimalism and foreshadowing of Expressionism’s concern with inner states. The print’s repeated exhibitions and publications have influenced generations of artists exploring figurative printmaking. Today, “Boys Bathing” stands as a touchstone for understanding Munch’s artistic evolution and his pioneering role in bridging Symbolism, Impressionism, and early modernist print media.

Conclusion

“Boys Bathing” (1899) encapsulates Edvard Munch’s mastery of translating psychological nuance into pared-down figuration and color. Through a balanced composition, complementary palette, and inventive woodcut technique, Munch transforms a simple bathing scene into a contemplative allegory of youth, vulnerability, and self-discovery. Situated within the artist’s broader body of work, the print marks a turning point from private anguish to communal ritual, even as it retains the introspective intensity characteristic of Munch’s vision. As both a technical achievement in color woodcut and a profound study of human emotion, “Boys Bathing” endures as a seminal work illuminating the depths that lie beneath the water’s surface.