Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

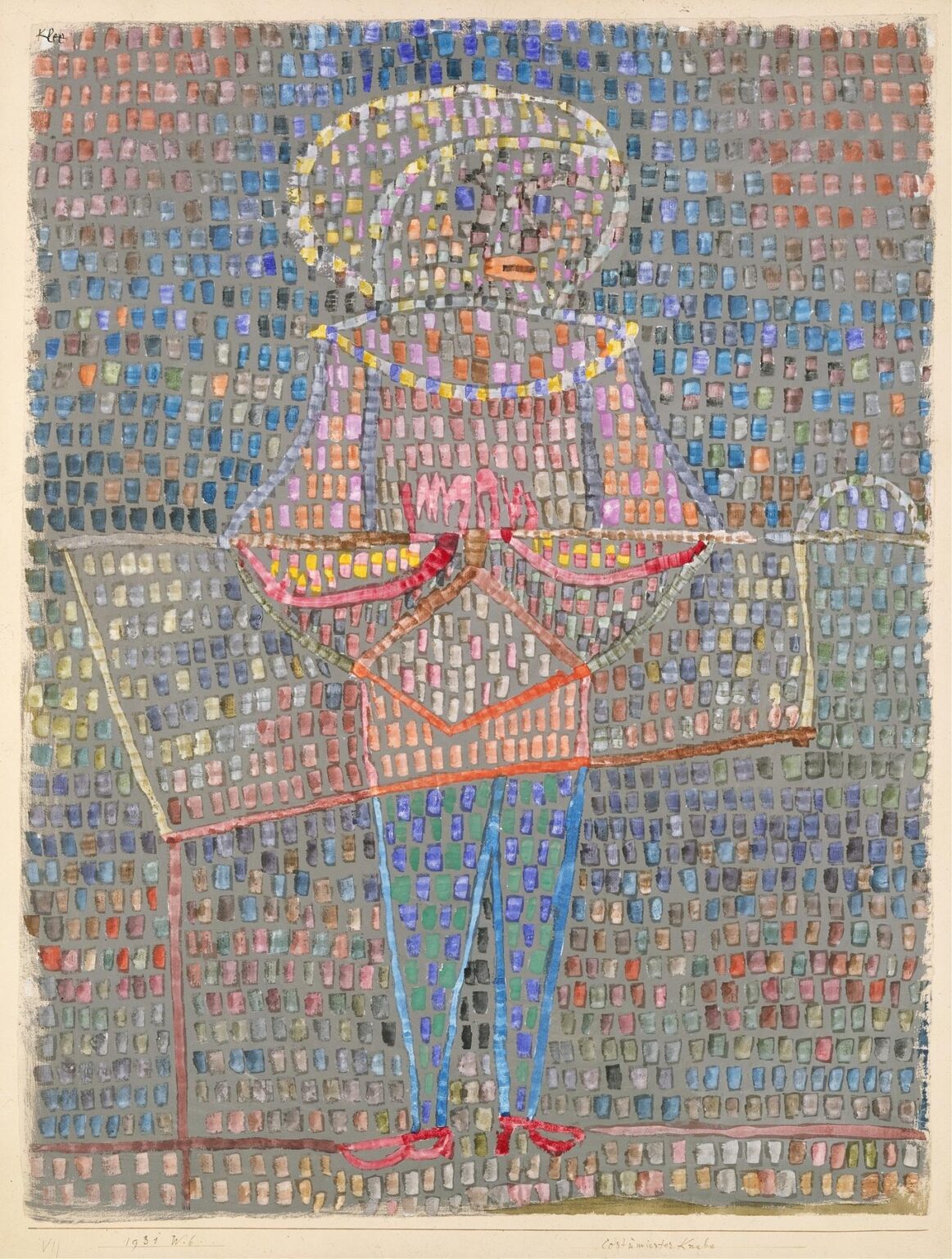

In Boy in Fancy Dress (1931), Paul Klee presents a richly textured vision of childhood and performance, rendered through his signature mosaic of colored dabs and geometric outlines. Far from a straightforward portrait, the work transforms a youthful figure into a symphony of color, form, and line, inviting viewers to explore themes of identity, disguise, and the liminal space between reality and fantasy. Painted during Klee’s tenure at the Bauhaus, this piece exemplifies his mature approach to abstraction—a marriage of playful imagery and rigorous structure that blurs the boundary between costume and canvas, actor and artwork.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1931, Klee was a leading instructor at the Dessau Bauhaus, where he had established a radical curriculum focused on the fundamental elements of art—point, line, plane, and color. Europe was confronting economic uncertainty amid the Great Depression, and artists grappled with questions of social identity and the role of art in turbulent times. Klee’s own life was shaped by his Swiss-German heritage, his earlier travels to Tunisia, and his deep fascination with children’s drawings and folk art. In Boy in Fancy Dress, these influences converge: the bright palette recalls Tunisian light, the mosaic technique hints at Byzantine tesserae, and the central figure resonates with the innocence and spontaneity of a child’s doodle.

Formal Composition and Mosaic Structure

The painting’s most arresting feature is its surface texture, achieved through countless small, rectangular dabs of pigment. These marks, applied in irregular rows, create a visual field that both fills and animates the entire picture plane. Within this shimmering matrix, Klee outlines the boy’s form in delicate but assured strokes of pastel or gouache—hat, torso, legs, and shoes emerge as geometric shapes defined by thin contours of muted orange and violet. The figure stands against an ambiguous, tessellated background; yet the limbs and hat break slightly beyond the implied horizon line, suggesting both rootedness and flight. The constellation of marks invites the eye to move across the surface in a gentle dance, discovering the boy’s form through the subtle interplay of positive and negative space.

Color Harmony and Emotional Atmosphere

Klee’s palette in Boy in Fancy Dress is at once vibrant and harmonious. Cool blues and greens predominate in the background and the figure’s leggings, while warmer pinks, lilacs, and ochres enliven the torso and hat. Bright red shoes and the rosy blush of fingertips and lips serve as focal accents, animating the composition like sparks. Each dab of color is not applied at random but selected to create optical mixtures: clusters of blue and green squares merge into soft turquoise when viewed at a distance; warm pink and orange dabs coalesce into a glowing flesh tone on the boy’s face and hands. This nuanced orchestration of hue exemplifies Klee’s belief in color as a musical instrument, each note contributing to a resounding emotional chord that resonates with both joy and introspection.

Costume and Identity: Disguise as Performance

The notion of “fancy dress” implies transformation and masquerade. The boy’s attire—wide-brimmed hat, flowing tunic, tight leggings, and pointed shoes—evokes medieval pageantry or commedia dell’arte, yet Klee abstracts these elements into simple forms: the hat becomes an arc of two concentric bands, the tunic a trapezoid festooned with small triangles, the legs two tapering rectangles. By reducing costume to its essential geometry, Klee underscores how clothing constructs identity and how the act of dressing up blurs the line between self and role. The boy is at once performer and character, his true self hidden beneath layers of color and line. This duality resonates with broader themes in Klee’s work: the interplay of inner life and outward appearance, the transformative power of art itself.

Line Work and Rhythmic Gesture

In Boy in Fancy Dress, Klee’s line is both foundation and flourish. The contour lines that define the figure are steady and assured, yet their pastel hue allows the background mosaic to shimmer through. Within the tunic, lightly sketched zigzags and scallops suggest embroidery or festooned trim, adding rhythmic variety to the blocky grid of color. The hat’s concentric arcs introduce circular motion into the predominantly rectilinear design, while the delicate vertical stripe at the figure’s midline provides a subtle axis of symmetry. Klee’s lines do more than outline—they choreograph the viewer’s gaze, leading it from the boy’s pointed toe, along his angular legs, across the decorative patterns of the costume, and up to the swirling band of the hat.

Thematic Resonances: Childhood, Play, and Mystery

Childhood occupies a central place in Klee’s imagination. He viewed children as natural artists, unencumbered by the preconceptions that constrain adult creativity. In Boy in Fancy Dress, the act of dressing up conjures the boundless possibilities of childhood play, where imagination reigns and identity is fluid. Yet there is also an undercurrent of mystery: the boy’s facial features are minimal—a small, puckered mouth, two dark dots for eyes—and his expression is ambiguous. Is he joyfully engaged in performance or quietly withdrawn into contemplation? This tension between exuberance and reserve mirrors the broader human condition: the tension between public persona and private self, between outward display and inner feeling.

Bauhaus Pedagogy and Theoretical Foundations

Klee’s teaching at the Bauhaus emphasized the primacy of elemental forms. In his Pedagogical Sketchbook, he wrote about the progression from dots to lines to planes, stressing that each mark contains latent potential for visual construction. Boy in Fancy Dress illustrates this theory: the mosaic dabs serve as points that articulate surface; the contour lines are the moving point, tracing form; and the resulting composition occupies the pictorial plane as a unified whole. Klee also advocated for art as visual music, and here the rhythmic repetition of colored marks functions like a melodic pattern, punctuated by the bright “chords” of red shoes and orange outlines.

Materiality and Technique

Executed on heavyweight Bauhaus watercolor paper, Boy in Fancy Dress combines watercolor, gouache, and pastel or tempera. Klee likely began with a broad gray wash to neutralize the ground, then sketched the figure’s outline in pencil. Over this foundation, he applied small squares of gouache or watercolor with a flat brush, carefully spacing them to achieve optical blending. The contour lines and costume decorations were added in pastel or opaque gouache, allowing for precise control and bold chromatic contrast. The layering of transparent and opaque media gives the surface a luminous depth, while the varied mark-making—soft wash, dabbing, linear sketch—creates an engaging tactile quality.

Relationship to Klee’s Broader Oeuvre

Boy in Fancy Dress joins a series of Klee’s works from the late 1920s and early 1930s that depict masked figures, harlequins, and dreamlike characters—images that reflect his interest in theater, ritual, and the subconscious. Unlike the highly detailed Magic Garden (1920) or the grand mosaic Ad Parnassum (1932), this painting is intimate in scale but ambitious in its textural complexity. It demonstrates how Klee could adapt his pointillist technique to figurative representation, merging the particle-like dabs of color with the taxonomy of human costume. The result is a work that is at once decorative and deeply psychological, bridging the gap between spectacle and introspection.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Possibilities

As with many of Klee’s works, Boy in Fancy Dress resists a single, definitive interpretation. Viewers may see reflections of childhood innocence, theatrical pageantry, or even subtle critiques of social performance. The figure’s anonymity—no name, no explicit narrative—invites personal projection: one might recall a child’s birthday party, a masked festival, or a theatrical rehearsal. The ambiguity of mood and the abstraction of detail encourage viewers to explore their own memories and emotions, making the painting a catalyst for individual reflection.

Legacy and Influence

Klee’s fusion of mosaic abstraction and figurative whimsy in Boy in Fancy Dress influenced the postwar generation of Color Field painters and pattern-based artists. His emphasis on color as dynamic energy resonated with painters such as Morris Louis and Paul Jenkins, while the integration of play and symbolism anticipated the narrative abstraction of artists like Philip Guston. Contemporary illustrators and graphic designers continue to draw on Klee’s approach, using pixel-like patterning and geometric simplification to evoke both modernity and timeless charm.

Conservation and Exhibition History

Preserving Boy in Fancy Dress requires careful climate control to protect the delicate watercolor and pastel marks. Museums housing the work frame it behind UV-filtering acrylic to prevent fading, and maintain humidity at around 50% to avoid paper cockling. High-resolution digital captures have allowed curators to examine Klee’s brushstrokes and color layering, revealing subtle revisions and underdrawings. The painting has featured prominently in retrospectives of Klee’s work, illustrating his role as a bridge between early modernist abstraction and later narrative figuration.

Conclusion

Paul Klee’s Boy in Fancy Dress (1931) stands as a masterful synthesis of color theory, formal structure, and poetic imagination. Through its intricate mosaic of colored dabs, confident linear outlines, and evocative costume motifs, the painting transforms a simple figure into a resonant symbol of childhood, performance, and the visionary possibilities of art. Rooted in Klee’s Bauhaus teachings yet suffused with personal whimsy, Boy in Fancy Dress invites viewers into a world where disguise becomes revelation, and the smallest mark can unlock a universe of meaning.