Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

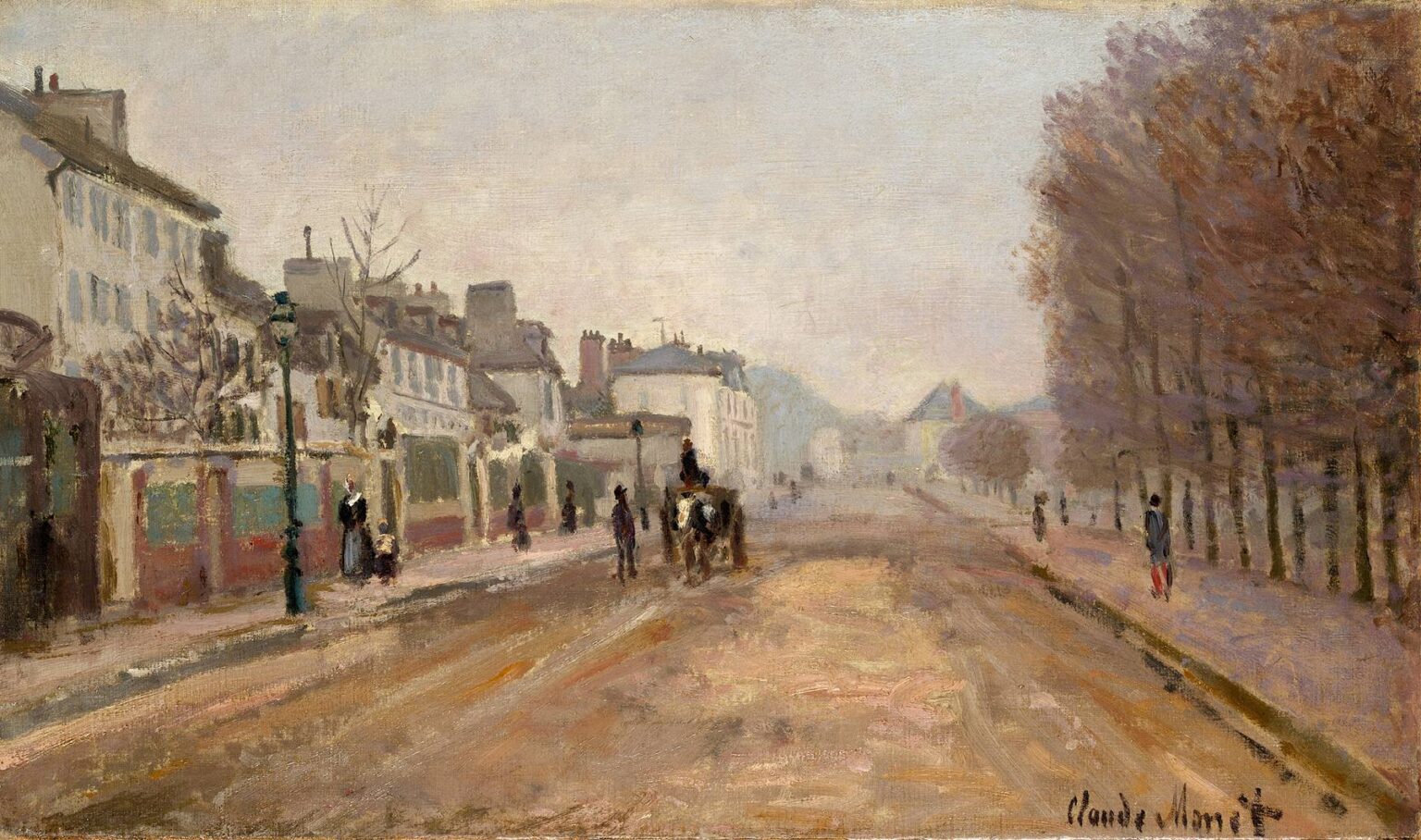

In Boulevard Héloïse, Argenteuil (1872), Claude Monet captures a fleeting moment of suburban life along a broad, tree-lined avenue bathed in diffused light. Unlike his more celebrated views of sailboats and riverbanks, this canvas focuses on the urban fringe where the rhythms of daily travel, commerce, and leisure converge. Through fluid brushwork, a subtle palette, and an acute sensitivity to atmospheric effects, Monet transforms an everyday street scene into a poetic study of modernity’s gentle pulse. The painting invites viewers to consider how light, color, and compositional rhythm can elevate a simple boulevard into an enduring symbol of Impressionist innovation.

Historical Context

By 1872, Monet was in the early stages of his Argenteuil period, having settled in the town on the Seine’s right bank the previous year. Argenteuil offered him both proximity to Paris via the newly extended railway and the appeal of suburban landscapes that combined pastoral charm with emerging urban infrastructure. The Franco-Prussian War had recently ended, and France was in the throes of modernization under the Third Republic. New boulevards, gas lamps, and bridges reshaped daily life, and Monet—ever the acute observer—pursued these transformations with his brushes. Boulevard Héloïse stands as a testament to his interest in recording the interplay between progress and nature.

Monet’s Argenteuil Period

Monet’s years in Argenteuil (1871–1878) marked a prolific phase in which he produced some of his most innovative plein-air works. He explored the Seine’s banks, garden interiors, and suburban streets, experimenting with broken color and fleeting atmospheric conditions. While river scenes like The Bridge at Argenteuil gained popularity, Monet also turned his attention to urban vistas. In Boulevard Héloïse, he extends the Impressionist doctrine—long applied to landscapes—into the realm of urban perception, capturing the gentle bustle of a town in transition and demonstrating that modern life itself could serve as a worthy subject for avant-garde painting.

Composition and Perspective

Monet arranges Boulevard Héloïse around a central perspective that recedes into the hazy distance. The wide roadway occupies the foreground, its surface articulated through horizontal brushstrokes that suggest the shifting textures of mud and cobblestone softened by recent rain. Flanking the boulevard, rows of bare trees frame the scene, their trunks forming rhythmic verticals that draw the viewer’s eye toward a vanishing point where buildings and figures dissolve into misty light. The left side features low façades and lampposts, while on the right a stand of taller trees casts pale shadows. This balanced interplay between horizontals and verticals evokes both stability and movement.

Light and Atmosphere

Light in Boulevard Héloïse is omnipresent yet elusive. Monet captures the soft glow of an overcast day, when sunlight diffuses through high clouds, permeating every surface with gentle uniformity. Highlights on building edges, lampposts, and the mud-churned boulevard shimmer without creating strong contrasts. The sky—a pale wash of grayed blues and warm neutrals—melds seamlessly with the rooftops, suggesting that air and matter are in continuous dialogue. This atmospheric integration exemplifies the Impressionist aim to portray not just objects but the ambient conditions that define how we perceive them.

Urban Leisure and Modernity

Although the painting contains no grand monuments, it conveys modern life through subtle cues: a horse-drawn omnibus mid-journey, small groups of figures strolling along sidewalks, and the geometry of urban planning manifest in the avenue’s width. These elements hint at the era’s evolving leisure culture, as middle-class inhabitants ventured outdoors for promenades and social encounters. Monet’s snapshot of suburban sociability underscores the democratization of public spaces, where artists, workers, and families mingled under gas lamps and newly planted trees—a reflection of France’s shift toward communal, open-air modernity.

Color Palette and Brushwork

Monet employs a muted palette of grays, ochres, and soft violets to capture the boulevard’s subdued elegance. Dabs of rose and pale green animate building façades, while touches of burnt sienna and umber register the earth’s warmth beneath damp skies. His brushwork remains characteristically loose: horizontal strokes define the road’s sheen, vertical slashes suggest tree trunks, and flickering dabs evoke distant figures. By juxtaposing complementary hues rather than blending them fully, Monet engages the viewer’s eye in optical mixing, fostering a vibrant surface that resonates with the play of light and shadow.

Spatial Depth and Movement

Despite its seemingly straightforward perspective, Boulevard Héloïse achieves a dynamic sense of depth through layered paint application and varying levels of detail. The foreground’s roadway is rich with textural complexity, while midground figures and carriages appear more generalized, their forms suggested through broad strokes. In the distance, buildings and human activity blur further, implying the boulevard’s extension into an indefinite horizon. This graduated reduction of clarity mimics human vision—sharp for nearby details, impressionistic for distant objects—and reinforces the painting’s immersive quality.

Human Figures and Narrative

While the figures populating Boulevard Héloïse are diminutive and sketchily rendered, they are essential to the painting’s narrative. A group of women in dark dresses chat by a lamppost, a solitary dog trots along the sidewalk, and a pair of children pause near the omnibus. These vignettes of daily life imbue the tableau with warmth and relatability. Monet refrains from spotlighting any single character; instead, he disperses human presence evenly, allowing the boulevard itself to function as stage and protagonist. This collective portrayal aligns with Impressionism’s democratic ethos—to depict modern life in all its multiplicity, without privileging grand historical or allegorical themes.

Architecture and Urban Fabric

The architectural elements in Boulevard Héloïse reflect Argenteuil’s mid-19th-century suburban vernacular: low-slung townhouses with shuttered windows, simple stucco facades, and modest commercial establishments. Monet captures these buildings with economy—just enough detail to convey their mass and texture, yet liberally allowing brushstrokes to suggest rather than define. The repetition of window rhythms and rooflines creates a visual continuity along the left edge, reinforcing the boulevard’s ordered elegance. Monet’s subtle inclusion of shopfront signage and wrought-iron fences hints at the burgeoning commercial life that animated suburban communities.

Monet’s Plein-Air Technique

Monet executed Boulevard Héloïse en plein air, applying paint directly on-site to capture the fleeting interplay of light, weather, and movement. His portable easel and small canvas enabled rapid responses to shifting conditions—an approach that privileged immediacy over meticulous finish. The resulting surface retains vestiges of Monet’s hand: visible brush marks, unblended pigment, and occasional areas of wet-on-wet blending. This immediacy contributes to the painting’s sense of spontaneity and authenticity, inviting viewers to share in the artist’s momentary experience of a rainy afternoon promenade.

Influence and Legacy

Although less famous than Monet’s water lilies or Rouen Cathedral series, Boulevard Héloïse played a role in expanding Impressionism’s thematic range. By turning his gaze toward suburban streets and quotidian activities, Monet inspired contemporaries and later artists to explore urban peripheries and the rhythms of modern life. Post-Impressionists like Pissarro and Signac followed suit, employing similar plein-air methods to depict cityscapes and boulevards. The painting’s emphasis on atmospheric effects also prefigured early explorations in abstraction, where light and color themselves became primary subjects.

Cultural Significance

Boulevard Héloïse resonates as a cultural document of a transformative era. The painting captures a moment when rapid industrialization, urban planning, and new social customs were redefining public spaces. Sidewalks lined with young trees, the presence of horse-drawn public transit, and groups of pedestrians strolling for pleasure reflect a society in flux—embracing both progress and pastoral respite. Monet’s sensitive portrayal transcends mere documentation, however; he imbues the scene with emotional resonance, reminding viewers that the essence of modernity lies in the lived experience of place and community.

Technical Analysis and Conservation

Recent technical studies of Boulevard Héloïse have revealed Monet’s material choices and process. Infrared imaging shows preliminary charcoal sketches mapping major architectural outlines and tree placements. Pigment analysis identifies natural ultramarine, lead white, yellow ochre, and viridian among Monet’s principal colors. Microscopic cross-sections demonstrate a multi-layered approach: a warm underpainting of earth tones provides depth, while thin glazes of cooler hues evoke atmospheric haze. Conservation efforts have focused on stabilizing minor paint loss along the canvas edges and cleaning accumulated surface grime to restore Monet’s original luminosity.

Reception and Provenance

Initially exhibited in private Argenteuil salons, Boulevard Héloïse found favor among local patrons before entering wider Impressionist circles. Early critics noted Monet’s departure from grand historical subjects in favor of suburban scenes, praising his fresh handling of light though questioning the sketchy finish. Over time, the painting garnered appreciation for its evocative atmosphere and technical daring. It eventually entered a prominent museum collection, where it has remained a key example of Monet’s Argenteuil output and an important milestone in the narrative of urban Impressionism.

Conclusion

Boulevard Héloïse, Argenteuil exemplifies Claude Monet’s ability to elevate the ordinary through a mastery of composition, color, and atmosphere. By painting en plein air and focusing on an unassuming suburban avenue, Monet demonstrates that modern life—its rhythms, textures, and ephemeral light—can inspire art of enduring beauty. The wide boulevard, framed by young trees and animated by carriages and passersby, becomes both subject and metaphor for Impressionism’s radical reimagining of painting. Nearly a century and a half later, Boulevard Héloïse continues to invite viewers into its hazy embrace, offering a timeless celebration of light, place, and community.