Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Figure Held by Air

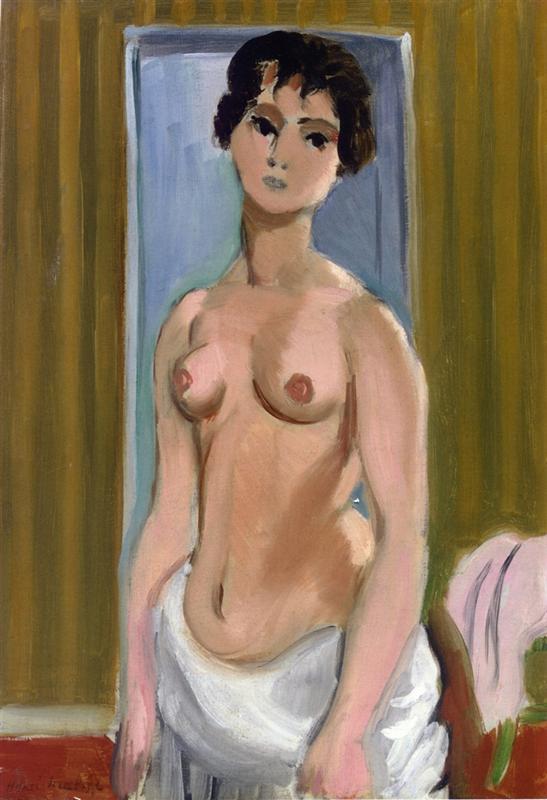

“Body of a Girl” (1918) stops the eye with a vertical, near-life-size presence: a young woman stands half draped before a cool blue opening, her torso turning gently as if toward light and air. Behind her, a rhythm of olive-gold stripes steadies the room; at the right edge a pink garment slips over a chair; below the navel a white cloth gathers around the hips. The figure is simplified but not schematic—flesh mapped by planes, edges elastic, and paint left vividly visible. Calm replaces bravura. The picture reads in one breath and then rewards patient looking as temperature shifts and brush tempos begin to register.

1918 and the Nice Turn

The date places the canvas at the doorway to Matisse’s Nice period. After a mid-1910s stretch of taut, sculptural experiments, he moved south and discovered a steadier light and a quieter grammar: color tuned by temperature rather than shock, space kept close to the plane, blacks used as positive, structural notes, and surfaces that breathe rather than glitter. This painting is a concise statement of that turn. It keeps the courage of simplification he had earned during his more radical years, yet it tempers the pitch—less shout, more poise; less rhetoric, more relation.

Composition: Column, Aperture, and Curtain

The design is spare and functional. The standing body operates as a central column, slightly off-center to the right. Behind it, a cool blue rectangle—window or door—functions as an aperture that ventilates the interior and offers a color counterweight to the warm flesh. The striped wall provides a soft grid that keeps the figure vertical while resisting rigidity. At the lower right, a small cluster of chair, drape, and pink cloth acts as a stabilizing ballast and as a reprise of the flesh note in another register. The whole composition fits the tall format like architecture: figure = column, aperture = light well, stripes = wall.

The Pose and Its Quiet Contrapposto

Matisse avoids theatrical gesturing. The model stands with a gentle, natural contrapposto: weight settled more on one leg, belly relaxed, shoulders angled slightly. Arms drop with minimal bend, palms turned inward—the most neutral stance a human can take while still being present. That neutrality is deliberate. It gives the painter full license to build expression from relationships—curves against planes, warm against cool, dark against light—rather than from narrative action.

Modeling by Temperature, Not Chiaroscuro

The torso is built with warm and cool passages rather than with heavy shadow. Warm, rosy ochres pool at the breasts, sternum, and belly; cooler grays and blue-violets slide along the ribcage and into the hollow under the shoulder. These temperature turns do the work of form without resorting to academic modeling. Flesh looks sunlit and breathable instead of sculpted from clay. Even the white drape follows the rule: warmer strokes crest the folds; cooler notes retreat into the troughs.

The Palette: A Balanced Chord

The canvas plays a concise but eloquent chord. Flesh occupies the warm center—peach, rose, and a muted gold—while the blue opening behind her supplies a cool equal and opposite. Olive-gold stripes in the wallpaper sit between the two, tying body to room; a small flare of pink on the chair echoes the cheeks and nipples; the drape’s whites, tinged with pearl-gray and a touch of lavender, gather light and calm the lower half of the composition. Because saturation is moderated, temperature carries mood. The result is daylight that feels continuous rather than staged.

Black and Near-Black as Positive Color

Matisse’s blacks are pigments, not voids. They define the hair, concentrate at the pupils, nip the edges of the lips, and flicker around the nipples as tight accents. These darks are never cheap outlines; they intensify adjacent color and anchor the airy palette. Where black meets blue, it cools and sharpens; where it touches flesh, warmth blooms; where it slides along the white drape, it clarifies the fold. The painting’s bass line is written in these few, deliberate darks.

Brushwork and the Time of Making

The surface keeps the time of its making. The blue aperture is laid in broad, vertical sweeps that leave long ridges; the stripes behind are pulled in steady strokes that settle like wallpaper; the flesh is constructed from shorter, directional passes that follow the turn of muscle and bone; the drape is churned with soft, circular touches. None of it is polished out. Each zone maintains its tempo—room steady, window slow, skin lively, fabric murmuring—so the figure appears to live in air, not on a poster.

Edges and Joins: How Forms Meet

Where flesh meets the cool opening, the edge breathes: a slight halo remains, the residue of wet-into-wet, and it reads as light. Where the torso crosses the striped wall, the seam is firmer, as though body presses gently against interior space. The drape’s top edge—a broken, warm-cool contour—both separates and binds belly to cloth. These tailored joins prevent simplified shapes from feeling pasted on, and they produce that elusive quality of shared atmosphere.

The Face: Abbreviation with Specificity

The head is small relative to the body, another classic Matisse decision that keeps attention on the torso’s lyrical geometry. Features are abbreviated to essentials: dark almond eyes, a quick shadow wedge under the nose, a minimal mouth with a cool highlight on the lower lip, and a lick of dark at the hairline. Yet the expression avoids masklike anonymity. The sitter’s gaze is frank and unforced—present without performing—an ethical stance that pervades Matisse’s figure work from this period.

The White Drape as Compositional Engine

More than modesty, the drape is a tool. It creates a bright, low anchor that balances the dense head; it introduces strong, vertical folds that echo and answer the wallpaper stripes; and it stages warm–cool play at the body’s edge where cloth and skin touch. Because the drape is painted with thin, light-catching paint, it keeps the lower half from feeling heavy—a pedestal of air rather than of stone.

The Room: Pattern as Calm, Not Clutter

Unlike Matisse’s later interiors crowded with pattern, this room is nearly ascetic. The striped wall is a soft metronome, not a spectacle. Its verticals steady the figure’s column and gently oppose the aperture’s broad plane of blue. The pink garment at the right provides a tender echo of the body while clarifying the chair’s geometry with almost no drawing. Pattern here is a structural device that makes calm.

Depth Kept Close to the Plane

The painting treats space as breathable layers rather than as deep corridor. Foreground (drape), middle (figure), and back (aperture and wall) interlock without drama. Overlap and value shifts do the work: the opening is cooler and lighter than the wall; the figure is warmer and more saturated than either; the chair is softened at the edge so it recedes. This keeps the picture readable as a designed surface while remaining convincing as a room.

Relation to the Odalisque Years

“Body of a Girl” foreshadows the odalisque series of the 1920s and early 1930s, yet it is leaner and less theatrical. There is no brocade overload, no labyrinth of props. The model’s privacy is intact; the dialogue is between body and air, not costume and ornament. In that economy lies the painting’s modernity. It proves Matisse did not need elaborate décor to summon the pleasure of looking—relations alone are enough.

Dialogues with Tradition

Matisse draws on classical precedent—the standing nude, the drape, the window of light—then rewrites it. Instead of polished marble flesh, he offers a surface where brushwork remains visible; instead of dramatic chiaroscuro, he models with temperature; instead of moralizing narrative, he cultivates presence. One hears whispers of Ingres in the smoothness of certain transitions, of Manet in the frankness of the gaze, of Japanese print design in the flat color areas—but the synthesis is unmistakably his.

A Guided Close-Looking Circuit

Begin at the cool blue opening behind the head and notice how its vertical sweeps are inflected by greener and bluer notes. Slide down the left contour of the shoulder, where a cool gray softens into warm flesh. Cross the sternum: a single, warmer stroke builds the bone; a cooler, violet smudge tucks under the breast. Pause at the navel; the belly’s roundness is stated by a temperature ring rather than an outline. Let your eye drop into the drape and watch how a warm fold turns with a single cool stroke. Travel up the right arm, catch the small flare of pink at the chair, and climb back into the face, where a wedge of shadow and a single highlight complete the mouth. Repeat the loop; rhythm replaces inventory.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Pentimenti remain: a shoulder trimmed and restated, a fold thickened and then pulled thin, a strip of blue reclaimed along the neck, a dark accent at the nipple reinforced late. Matisse does not buff these traces away. He stops when relations ring true. That earned inevitability—nothing superfluous, nothing missing—is what gives the picture its quiet authority.

The Ethics of Presence

Matisse’s nudes from this moment resist both coyness and conquest. Here, the model’s stance and gaze are open without being staged; the painter’s attention is formal without being cold. The body is not an anecdote but a coordination of color, contour, and air. This ethical clarity—respect for the sitter, for looking, and for the viewer’s space—helps explain why the canvas still feels fresh.

Lessons for Painters and Designers

The painting operates as a compact manual: construct with temperature; use black as living color; let pattern steady rather than shout; design vertical formats architecturally; vary edge quality to seat forms in shared air; and keep depth near the plane so the image reads instantly yet deepens with time. Above all, trust a handful of true relations to carry all the feeling you need.

Why It Still Looks New

A century on, “Body of a Girl” aligns with contemporary eyes. Big shapes read at once; color is sophisticated rather than loud; process is visible and honest; and space is shallow enough to sit comfortably beside photography and graphic design. Most important, the picture trusts exact relations—blue behind warm flesh, olive stripes around a white drape, a few decisive blacks—to conjure presence. That trust is the heart of Matisse’s modern classicism.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Ease

“Body of a Girl” is not a spectacle; it is an architecture of ease. A column of flesh stands before a well of air; a soft metronome of stripes keeps time; a white drape gathers light; a small pink echo confirms warmth. With these few elements, Matisse builds a room where looking is unhurried and exact, where serenity results from measure rather than from emptiness, and where the human body appears not as an occasion for narrative but as the perfect instrument for color and light.