Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

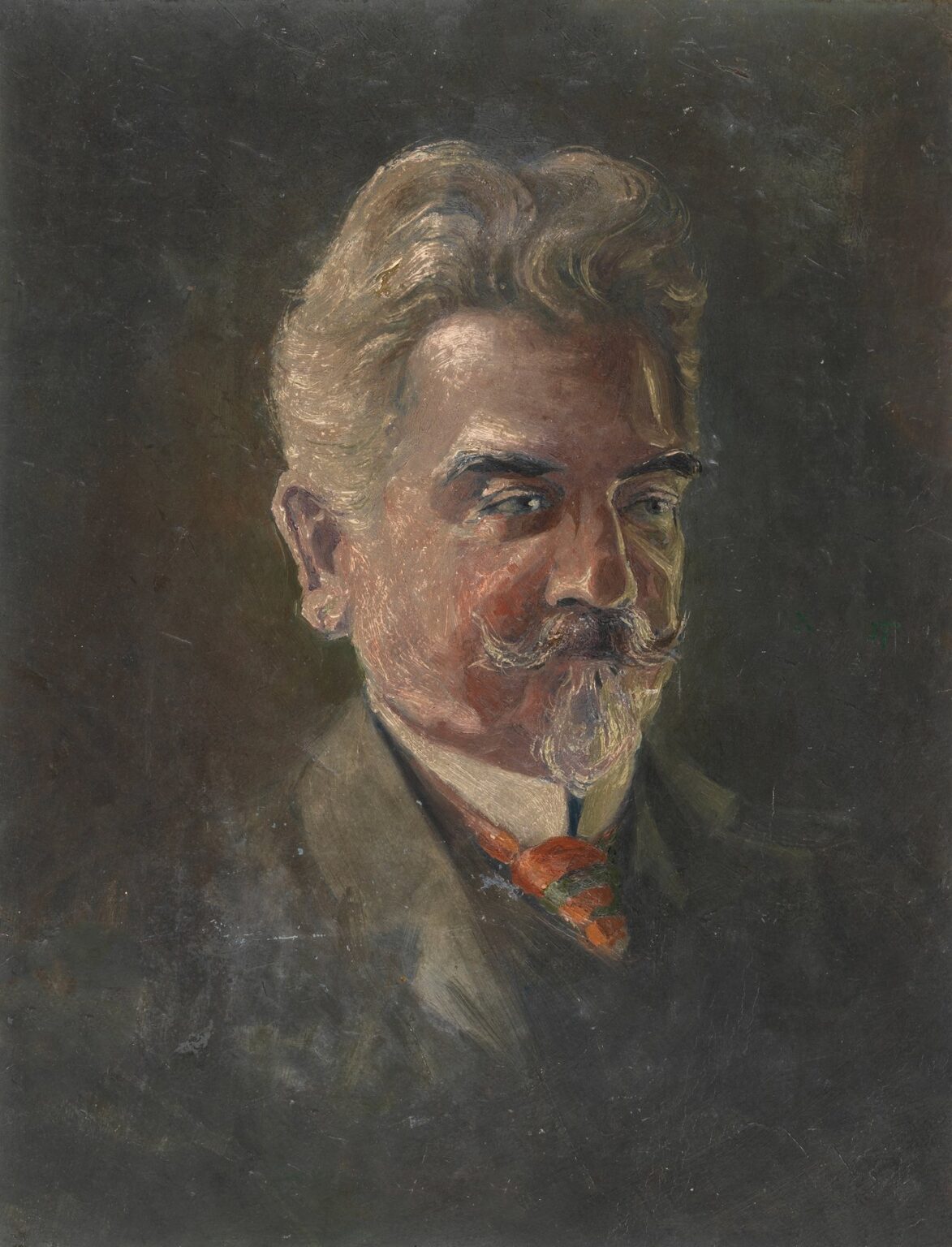

Egon Schiele’s Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek (1907) marks an important early milestone in the artist’s portraiture, revealing his burgeoning command of character study, formal innovation, and psychological insight. Painted when Schiele was just fourteen or fifteen years old, this work transcends its youthful origins through its nuanced handling of pose, color, and brushwork. Leopold Czihaczek, the sitter, was a friend and fellow student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, and Schiele’s portrait captures both the uniqueness of his features and a deeper sense of inner life. The painting’s dark, almost abstract background sets the stage for a luminous head-and-shoulders depiction of Czihaczek, whose gaze shifts subtly to the side, inviting reflection on the relationship between artist and subject. In the following analysis, we explore the historical backdrop, composition, use of line and color, psychological resonance, technical approach, and the painting’s place within Schiele’s evolving oeuvre.

Historical Context

In 1907 Vienna, the art world was in flux. The Secession movement, spearheaded by Gustav Klimt and members such as Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, challenged the conservative academic establishment, advocating for new aesthetic languages and the integration of fine and applied arts. Schiele, who enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts later that year, found himself drawn to Secessionist debates even as he chafed under the institution’s traditional methods. Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek emerges at the cusp of Schiele’s formal training and his departure from academic realism. The broader cultural milieu—marked by rapid industrialization, shifting social mores, and the rising tensions that would lead to World War I—infused Viennese art with a sense of urgency and introspection. Against this backdrop, Schiele’s portrait of fellow student Leopold Czihaczek stands as both an homage to classical portraiture and a harbinger of Expressionist experimentation.

Subject and Composition

Leopold Czihaczek sits in three-quarter view, his shoulders angled slightly away from the viewer while his head turns inward. This pose creates a gentle tension between stability and movement: the shoulders anchor the figure, while the turned head introduces psychological depth. The composition is tightly cropped, focusing attention squarely on the sitter’s face and upper torso and eliminating extraneous background detail. The background itself is painted in deep, muted browns and greens, recalling the earth tones favored by Klimt’s circle yet applied with a simplicity that foreshadows Schiele’s later flat planes of color. Czihaczek’s suit is similarly rendered in dark hues, its lapels and collar outlined with minimal but confident brushwork. The bright white of his shirt collar and tie knot serve as visual anchors, drawing the viewer’s eye to the region of greatest emotional subtlety: the interplay of gaze, expression, and the faint flush of the cheeks.

Use of Line and Form

Line plays a pivotal role in Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek, bridging the realms of drawing and painting. Schiele characteristically draws sharp, assured contours around the face, shoulders, and clothing, lending sculptural clarity to the sitter. These lines define planes of the face—along the cheekbones, jawline, and brow—while internal hatching and cross-hatching suggest the volume of the skull and muscular tension. The hair is treated with short, choppy strokes that capture both the sitter’s coiffure and the restless energy of youth. Notably, the lines around the eyes and mouth are thinner and more tentative, inviting the viewer to linger on the portrait’s most expressive features. This economy of line, combined with deliberate distortions—such as the slight elongation of the neck and the narrowing of the shoulders—underscores Schiele’s commitment to conveying emotional truth over slavish anatomical accuracy.

Color Palette and Tonal Harmony

The palette of Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek is marked by its restraint and subtlety. The background’s dark browns and olive greens envelop the figure without competing for attention, creating a stage upon which Czihaczek’s flesh tones and clothing details emerge. Schiele employs muted ochres and pinks to model the sitter’s skin, layering thin glazes that allow the underpainting to glow through. The warm tones of the cheeks and forehead contrast with cooler greys and greens in the shadows of the face, producing a nuanced chiaroscuro that feels more luminous than heavy. Czihaczek’s suit is rendered in a nearly monochrome dark brown, with light highlights along the lapels and shoulders suggesting the material’s texture. The white of the shirt collar and tie knot introduces a stark visual contrast that anchors the portrait’s center. Overall, Schiele’s harmonized color scheme establishes a mood of quiet introspection and underscores the sitter’s individuality.

Light and Shadow

Schiele’s approach to lighting in this portrait is subtle yet effective. There is no single, dramatic light source; instead, the face is gently modeled through soft transitions between light and shadow. The sitter’s left cheek and forehead receive the lightest touches of pigment, while the right side of the face recedes into deeper, cooler hues. The subtle shifting of tone across the bridge of the nose, the eyelids, and the hollow beneath the cheekbone shapes the sitter’s gaze, lending energy to his sideways glance. On the clothing, highlights trace the contours of lapels and shoulder seams, suggesting the gentle fall of light across tailored fabric. The background itself appears to absorb light rather than reflect it, further isolating Czihaczek’s visage in a softly illuminated bubble. This thoughtful modulation of light and shadow enhances the portrait’s psychological depth.

Brushwork and Texture

A close examination of the painting’s surface reveals Schiele’s early explorations in brushwork. The background is built up in layered, directional strokes that create a subtly variegated texture, hinting at a space that is both atmospheric and abstract. The sitter’s face is painted with more controlled, smaller brushes, each stroke following the underlying underdrawing and sculpting the features with precision. In the hair, longer, more fluid strokes suggest individual strands while retaining a painterly freedom. The suit’s broad swathes of darker pigment are applied in a slightly thicker consistency, registering the materiality of the canvas and the physicality of the paint. Schiele’s decision to leave occasional brush marks visible—rather than pursuing a fully polished finish—underscores the painting’s vitality and the immediacy of the artist’s hand.

Psychological Depth and Expression

Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek transcends its status as a student exercise through Schiele’s ability to capture the sitter’s psychological resonance. Czihaczek’s gaze is not directed at the viewer but drifts slightly to one side, as though he is caught in a moment of internal reflection. His lips are gently pressed, neither fully relaxed nor rigid, suggesting the tension between self-assuredness and youthful uncertainty. The slight arch of the eyebrows and the furrow between them hint at curiosity or mild concern. The sitter’s posture, with one shoulder marginally higher than the other, conveys a naturalism that contrasts with the strong linearity of the composition. Through these subtle gestures, Schiele gives life to Czihaczek’s inner world, making the portrait not just an external likeness but a window into the sitter’s character.

Technical Innovations

Although Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek predates Schiele’s radical Expressionist breakthroughs, it already displays technical innovations that would characterize his mature work. The seamless integration of underdrawing and thin oil glazes—where the pencil or charcoal lines remain visible through washes of pigment—anticipates Schiele’s later technique of layering to achieve luminance. His willingness to distort proportions for expressive effect, such as the sitter’s elongated neck and the slightly exaggerated jawline, foreshadows the dramatic distortions in his subsequent figure paintings. Moreover, the atmospheric background, free of detailed setting, points toward a modernist reduction of environment in favor of psychological space. These early experiments in technique underscore Schiele’s relentless pursuit of a personal style that would soon redefine European portraiture.

Relationship to Schiele’s Oeuvre

Within the chronology of Egon Schiele’s work, Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek occupies a key position at the intersection of academic training and personal expression. Completed shortly after his enrollment at the Academy and before his celebrated self-portraits of 1910, it reveals the young artist absorbing lessons from Klimt’s circle while simultaneously chiseling away the decorative flourishes in favor of a more direct, introspective approach. Compared to Klimt’s luminous, ornamental palette and sumptuous surfaces, Schiele’s portrait of Czihaczek is leaner, more restrained, and more concerned with psychological truth. This painting thus serves as a bridge between the lingering influence of Viennese Secession and the raw immediacy of Schiele’s later Expressionism. It also highlights his early affinity for commissioned portraiture—a strand of his career that ran parallel to his more provocative nudes and self-images.

Reception and Legacy

While Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek did not achieve the notoriety of Schiele’s later, more controversial works, it garnered attention within his peer group and among early supporters such as Leopold Czihaczek himself. The sitter’s endorsement lent credibility to Schiele’s emerging talent, helping him attract further commissions. In subsequent decades, the portrait has been reappraised by scholars tracing Schiele’s development, often cited as a first glimpse of the artist’s capacity for psychological depth and formal boldness. Exhibitions of Schiele’s student and early works place this portrait in the context of a prodigious adolescent sensibility, demonstrating how he assimilated and transcended academic conventions. Its legacy endures in the way it foreshadows the explosive creativity that would define European painting in the years leading up to World War I.

Conclusion

Egon Schiele’s Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek stands as a testament to the artist’s early mastery of portraiture, combining deft composition, expressive line, and a carefully harmonized palette to evoke the sitter’s individuality and inner life. Painted at the dawn of Schiele’s career, it reveals an artist already probing the boundaries between realism and psychological expression, between academic convention and personal innovation. Through its thoughtful interplay of light and shadow, its layered brushwork, and its nuanced rendering of gaze and posture, this portrait transcends its origins as a student exercise to earn a lasting place within Schiele’s oeuvre. As a bridge between the decorative Secession and the visceral intensity of Expressionism, Bildnis Leopold Czihaczek offers viewers a compelling glimpse of an artist in formation and the timeless power of portraiture to capture the essence of the human spirit.