Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

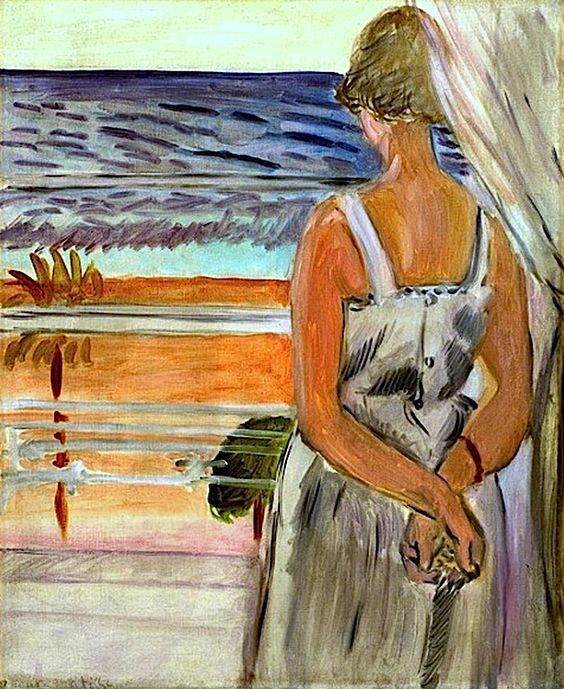

Henri Matisse’s “Beside the Window” is a quiet, luminous drama about standing between worlds. A woman faces away from us toward the Mediterranean, framed by the pale fall of a curtain. Her hands are loosely clasped behind her back; the straps of a light summer dress rest across sun-warmed shoulders; and beyond the balustrade bands of ochre beach, turquoise shallows, and deep blue sea advance in long, horizontal breaths. With very few elements—figure, curtain, balcony line, water and sky—Matisse composes a scene where looking outward becomes the subject. The painting belongs to the Nice period, when he developed a modern classicism grounded in calm, clarity, and the felt truth of relations rather than spectacle.

A Nice-Period Threshold Between Interior and Exterior

Matisse made many interiors in Nice that revolve around windows and doors, but this image is among the most distilled. We are not given the furniture of the room, only a soft edge of curtain at right and the architectural band of the balcony. Everything else is light and distance. The woman becomes a mediator: her body occupies the here of the room while her attention goes to the there of the sea. The composition therefore does not describe narrative action; it stages a balanced listening—how an interior receives the world and how the world, in turn, enters the room as color.

Composition Organized by Uprights and Bands

The painting is built from a few strong bearings. Two verticals stabilize the field: the figure and the pale curtain. Across them run a series of horizontal registers—the ochre beach, a bright strip of surf, the violet- and indigo-streaked sea, and the pale, lightly clouded sky. Where vertical and horizontal meet, the picture finds poise. The woman’s back occupies the right third of the canvas, leaving the left two-thirds for the view; the balcony rail crosses her waist, linking body to landscape without cutting her in two. The eye moves seamlessly from the curve of shoulder to the band of surf, from clasped hands to the reflective shallows, and then out toward the darkening water.

Color Climate: Ochre, Turquoise, Violet, and Flesh

Matisse engineers a gentle but vivid palette. The lower beach is blushed with warm ochres that lean toward apricot near the surf; a thin, bright turquoise sits just beyond the shore; and the sea is constructed from long, loaded strokes of violet and cobalt that deepen toward the horizon. These bands wrap the scene in marine light. Set against them, the figure’s skin is a warm honey toned by rose along the neck and shoulders. The dress reads as silver-grey washed with subtle lilacs, so it participates in the seascape’s coolness while remaining distinct from it. The curtain, nearly colorless, carries a whisper of the room’s neutrality and keeps the right edge open to air.

The Figure as Hinge and Measure

Seen from behind, the woman is all posture, not portrait. Her weight falls slightly on the right leg; the left knee softens forward; the arms fold behind with an ease that suggests unselfconscious standing. This pose does more than describe leisure—it calibrates the space. Her shoulders measure the distance to the horizon; her clasped hands sit where the balcony’s top edge would brush the body; her head tilts toward the surf line as if listening. By refusing overt facial expression, Matisse grants the entire body the task of attention. The figure becomes the hinge on which inside and outside swing together.

The Curtain’s Gentle Authority

The pale curtain along the right edge is scarcely a thing and yet it is crucial. Its soft vertical clarifies the painting’s scale; its light opacity acknowledges the room; and its wavering edge provides a visual breath against the more assertive contour of the figure. The curtain’s whiteness also acts as a reflector—cooling the shoulder and the side of the dress nearest it, registering the nearness of shade. Without it, the composition would skew too far toward the open view; with it, the painting keeps faith with the interior.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Seeing

The surface of “Beside the Window” wears its making openly. The sea is constructed from long, horizontal drags that leave ridges and tiny gaps, like wind’s skimming trace on water. The pale surf is a clean, thin sweep, while the beach is a looser, scumbled field in which the brush turns and lifts. In the figure, paint is thinner; soft modulations over the shoulder and back allow the canvas to breathe through, giving skin a living translucency. In the dress, swift vertical licks suggest both the fall of fabric and the verticality of the figure herself. Everywhere, Matisse stops as soon as a passage “reads,” preserving freshness and preventing the scene from hardening into illustration.

Light Distributed Like Air

There is no spotlight in this picture. Illumination is a set of relationships. Skin warms toward the left where reflected beach light rises; it cools near the curtain’s white; the dress catches a faint violet from the sea; and the sea itself steps from darker indigo to paler violet as it approaches the sand. The effect is not stagey; it is atmospheric. The room’s light feels gently invaded by the world outside, and the outside seems to be breathing light into the interior. That sense of mutual exchange is the true subject: an economy of light rather than a report of objects.

Pattern Turned Into Rhythm

Matisse hints at pattern without enclosing anything in ornament. On the beach, small, spare marks read as mirrorlike pools or palm reflections, placed in a cadence that pulls the eye laterally. At the far left edge, vertical strokes echo the balcony balusters, each a small beat that answers the sea’s horizontal rhythm. The dress, with its narrow straps and stitched seams, carries a vertical tempo that harmonizes with the curtain. All of this is understated, but it keeps the picture from dissolving into broad bands; rhythm gives the eye something to count softly while it rests.

Space Held Close to the Surface

Depth here is a matter of stacked planes rather than plunging perspective. Balcony edge, beach, water, sky are laid like sheets against the picture plane. The figure overlaps them without breaking the integrity of the bands. Because the sea is rendered as a surface, not a hole, the window is not a tunnel through which we escape; it is a membrane across which we see and feel. This is a hallmark of Matisse’s modern classicism: honoring the flatness of the canvas while delivering true sensation of space.

The Psychology of Looking Out

Although we cannot see the woman’s face, the painting communicates a precise psychological register. Her clasped hands suggest patience; the forward lean of the neck suggests attention; the squared shoulders, unguarded. She is not waiting for someone, nor is she posed for our benefit. She is simply aligned with the sea’s tempo. The choice to deny the viewer a facial expression deepens this mood. We are invited to occupy her act of looking rather than to analyze her character. In that sense, the painting is less a portrait of a person than a portrait of a state of mind: quiet expectancy that edges toward contentment.

Dialogue With Sister Windows

“Beside the Window” speaks to Matisse’s many Nice-period windows and verandas. Where some include patterned floors and still-life tables, this picture strips the interior to curtain and figure, intensifying the exchange between human presence and landscape. Compared to the more theatrical “Open Window” scenes, the palette here is gentler and the horizon lower; the woman’s back prevents the view from turning into a postcard. Relative to later odalisques posed near windows, the emphasis is less on decorative abundance and more on the equilibrium of bands and upright—a modern classicism that favors poise.

The Dress as Mediator of Temperatures

The dress is a quiet masterpiece of tuning. Its grey-white fabric is not dead; it is woven from cool violets, warm greys, and lingering touches of ochre drawn from the shoulder and forearm. In doing so it mediates the palette’s extremes: it accepts coolness from the sea and warmth from the beach while remaining a distinct interior tone. The thin straps, lightly shadowed, amplify the geometry of the shoulders and pull a narrow but decisive line across the composition at the same height as the surf. What looks like simple clothing is actually a color instrument that stabilizes the painting’s climate.

The Viewer’s Circuit Through the Image

The painting invites a reliable path for the eye. Most viewers enter at the bright shoulder and neck, descend along the spine to the clasped hands, step left across the balcony band to the pale surf, then drift outward over the layered sea toward the horizon. From there the eye returns through the curtain’s soft vertical and back to the shoulder. Each circuit offers small incidents: a warmer knot of paint at the nape, a flick of green in the palm frond reflection, a faint blue shadow on the dress seam, a transparent drag that lifts the sky toward white. Because the path is smooth and replenishing, the painting supports long looking without fatigue.

Sensation Over Description

The strength of the canvas lies in sensation. You can feel late light slanting off the beach; you can sense a breeze tugging the curtain; you can hear, almost, the small regular breathing of waves approaching the sand. None of this is accomplished by descriptive detail. Instead Matisse calibrates color intervals and edge pressures so that the relations produce the sensation. The sea’s long strokes tell more truth than a thousand meticulously drawn ripples; the dress’s lilac greys convey more air than a rendered lace pattern would. The painting honors the viewer by trusting perception.

The Ethics of Calm

Matisse famously wished his art to be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind.” “Beside the Window” takes that wish seriously without lapsing into sentimentality. Calm here is not emptiness; it is compatibility—every element seated comfortably next to its neighbor. The body rests within the room; the room opens to the sea; the sea returns light that bathes the body. The balance feels earned, not perfumed. In an age already acclimating to speed and spectacle, such an ethic reads as quietly radical.

Why the Image Endures

The picture lasts because its order feels inevitable once seen. A figure and a curtain, a band of balcony, beach, sea, and sky—nothing more is necessary. The intervals are right; the temperatures are right; the edges breathe. The absence of the face, far from withholding meaning, releases it. Any viewer can step into the posture of looking and share the moment’s balanced attention. It is a painting one carries like a remembered pause: the instant when air from the sea reaches the skin and thoughts fall into the rhythm of waves.

Conclusion

“Beside the Window” refines the Nice-period window motif to its essentials. Two verticals—a woman and a curtain—stand before a slow chord of horizontal light. Color is tuned into climate; brushwork remains candid; depth holds close to the surface so that the act of seeing becomes the event. Matisse’s art of poise is fully present: a humane classicism in which inside and outside meet with tact, and a person finds a moment of recognition in the measured breathing of the sea. The painting does not describe what she sees; it teaches us how to stand beside a window and look.