Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

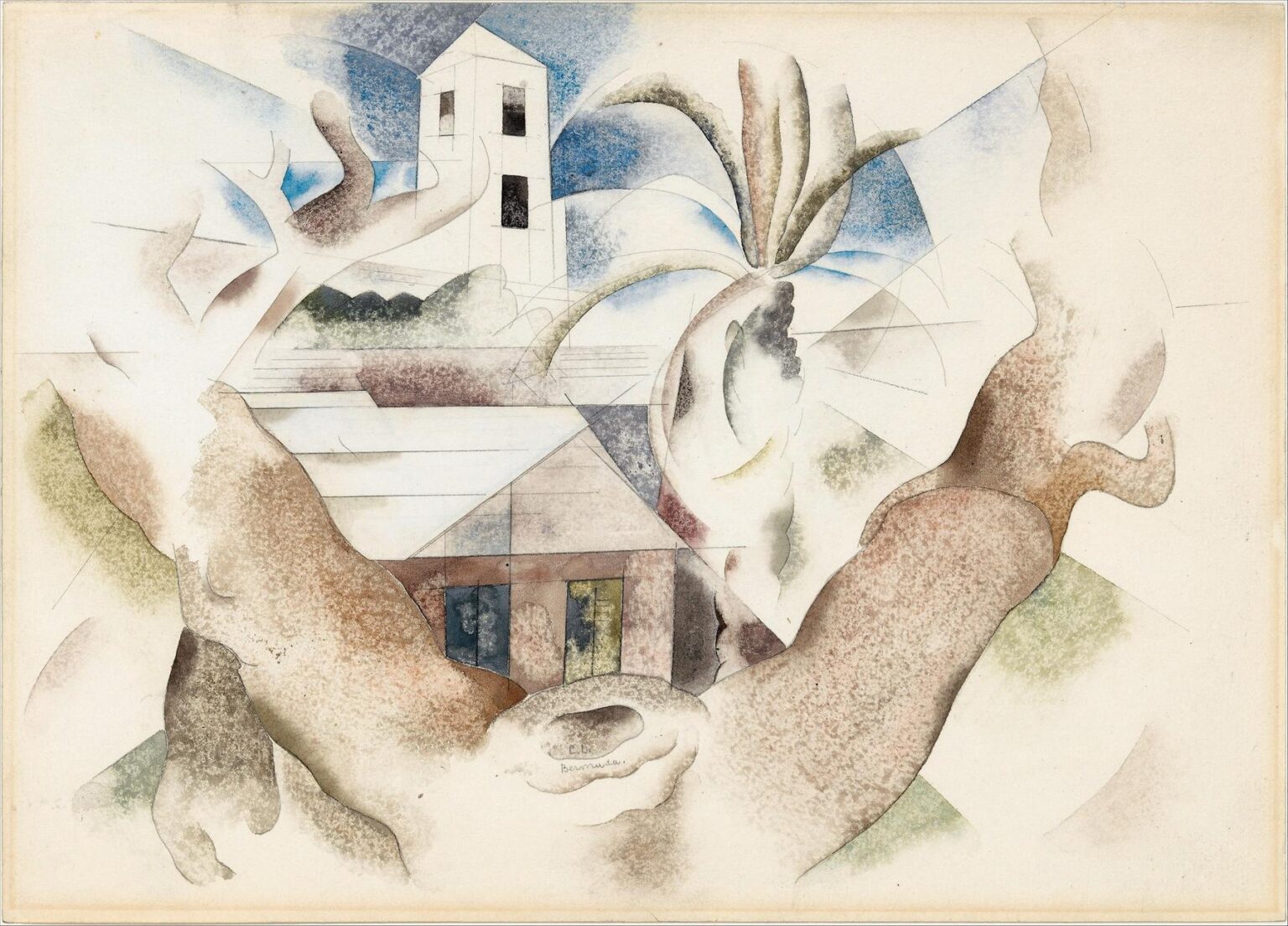

Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House (1917) by Charles Demuth marks a pivotal moment in the artist’s transition from precisionist urban scenes to a more lyrical, nature‑inflected modernism. Executed in watercolor and pencil, this work refracts a simple island vista—a solitary house and sprawling tree—through a Cubist‑inspired prism of fractured planes and subtle tonal washes. Demuth eschews straightforward representation, instead inviting viewers to piece together the landscape from interlocking geometric shapes, layered transparencies, and the paper’s pristine negative space. The result is both serene and intellectually charged: a poetic meditation on light, form, and the dialogue between structure and organic growth.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1917, Charles Demuth had emerged as one of America’s leading modernists, renowned for watercolors that distilled factories, bridges, and urban architecture into crystalline compositions. His precise lines and flat color fields aligned him with Precisionism, a movement that celebrated industrial America’s clarity and order. Yet the Bermuda sojourn—prompted by an invitation from architect Paul Cret—offered Demuth a dramatic new palette: pastel‑stucco buildings, swaying palms, and the island’s luminous atmosphere. In Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House, Demuth synthesizes his rigorous structural sensibility with a newfound fascination for natural forms and tropical light, producing a work that bridges urban precision and pastoral abstraction.

Composition and Structural Dynamics

Demuth anchors the composition on a central vertical axis formed by the watercolor‑rendered facade of a house. Flanking this are the arcing limbs of a massive tree, their sinuous curves delineated by variegated washes of brown and ocher. Behind and around these primary forms, Demuth arranges a constellation of angular planes—triangles, parallelograms, trapezoids—that suggest distant hills, rooflines, and sky. Faint pencil underdrawings remain visible beneath the washes, revealing the careful planning of intersecting lines and vantage shifts. Large expanses of untouched paper dominate the periphery, creating a halo of negative space that both contains and amplifies the central cluster of activity, lending the scene a sense of buoyant suspension.

Interplay of Line and Wash

A defining feature of Demuth’s Bermuda watercolors is the seamless integration of precise pencil contours with fluid watercolor washes. In this work, thin graphite outlines establish the geometric framework: the slightly off‑kilter edges of the house’s walls, the subtle arcs of roof planes, and the foundational structure of the tree trunk. Over these, Demuth applies watercolor with remarkable restraint, allowing pigments to mingle and fade at the edges. The washes range from diaphanous—almost imperceptible lavender hints in the sky—to more saturated applications on the tree bark. This interplay of line and wash generates a dynamic tension: the pencil confers architectural rigor, while the watercolor evokes the lush unpredictability of nature.

Color Palette and Light Effects

Where Demuth’s earlier industrial scenes often featured stark grays and crisp whites, Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House adopts a softer, sun‑washed palette. The house’s walls glow with pale rose and sandy beige, recalling the island’s shell‑lime renderings. The tree’s limbs and foliage emerge in earthy browns, umber, and muted green washes that accumulate in granular textures suggestive of bark and lichen. In the background, translucent blues and grays imply distant hills and the tropic sky. Crucially, significant areas remain unpainted, their virgin paper surface serving as highlights that suggest beams of sunlight or the halo of bright air. Through these chromatic choices, Demuth captures the transient brilliance of Bermuda’s light while maintaining the painting’s overall sense of calm abstraction.

Fragmentation and Cubist Influence

While Demuth never aligned himself explicitly with Cubism, his Bermuda landscapes reveal clear affinities with Cubist methodologies. The landscape is not depicted as a single, unified vista but rather fractured into multiple facets that viewers mentally reassemble. Rooflines slice through tree branches; hills overlap with walls; arcs of sky intersect with diagonal field edges. Yet unlike Cubist still lifes dense with overlapping objects, Demuth’s planes remain airy and provisional, allowing the eye to roam freely. This measured fragmentation dissolves the boundary between man‑made structure and natural environment, reflecting a modernist fascination with simultaneity and the breakdown of traditional perspective.

Spatial Depth through Overlap

Demuth achieves a convincing sense of depth without resorting to linear perspective or vanishing points. Instead, he relies on the strategic overlapping of translucent planes. Warmer, more opaque shapes in the foreground—such as the tree trunk and the house facade—sit atop paler, more attenuated washes that recede toward the background. The interplay of warm browns and cool blues further reinforces this spatial layering, guiding the viewer from the immediate plane of the tree and building toward the distant horizon. Horizontal pencil strokes at the lower right suggest ground planes or planks, orienting the composition and lending subtle clues to the viewer’s vantage point.

Relationship between Natural and Built Forms

In Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House, Demuth explores the dialogue between architectural and organic forms. The house’s rigid rectangular walls contrast with the tree’s curving, anthropomorphic limbs. Yet their interpenetration—branches partially obscuring walls, geometric shapes slicing through organic forms—suggests a harmonious coexistence. Rather than privileging one over the other, Demuth integrates both into a single pictorial architecture. The result is a visual metaphor for human‑nature interdependence: the built environment anchors us, while nature reclaims and enfolds human efforts with graceful persistence.

Technical Mastery of Watercolor

Watercolor demands control over water, pigment density, and timing—qualities Demuth demonstrates with exceptional skill. He employs wet‑on‑wet techniques to create softly mottled backgrounds, capturing the ephemeral patterns of tropical light. Wet‑on‑dry applications yield sharper edges and more intense color where needed, such as along the tree’s gnarled ridges. His pigment mixtures avoid muddiness, retaining clarity even in layered regions. Pencil underdrawings remain partially visible, testament to the artist’s deliberate planning. The harmony between line and wash, precision and spontaneity, underscores Demuth’s belief in watercolor’s potential for both structural rigor and lyrical expression.

Symbolic Resonances

Beyond its formal intricacies, Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House carries symbolic weight. The solitary house can be read as a symbol of human shelter and aspiration, its shattered planes perhaps alluding to the fragility of human constructs under nature’s gaze. The tree—ancient, rooted, sprawling—embodies resilience and the inexorable cycles of growth. Their juxtaposition, sublimated into modernist abstraction, evokes broader themes of permanence and transience, control and surrender. The expanses of white paper might symbolize pure air or spiritual openness, inviting contemplation beyond the material forms.

Place within the Bermuda Series

Demuth’s Bermuda series—watercolors produced between 1916 and 1919—captures his evolving response to a novel environment. Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House inaugurates this exploration with a balanced fusion of structural clarity and organic imagery. Subsequent works would intensify fragmentation or explore denser color fields, but this initial painting establishes the series’ foundational approach: geometric decomposition of landscape tempered by generous negative space. When viewed alongside his precisionist industrial scenes, Bermuda No. 1 reveals Demuth’s remarkable versatility and his belief that modernist formal strategies could illuminate both steel structures and sun‑lit island vistas.

Emotional and Intellectual Engagement

Despite—or because of—its abstraction, Bermuda No. 1 invites both emotional resonance and intellectual curiosity. The painting’s tranquil palette and open composition evoke the comfort of a secluded dwelling beneath branching shade, while its fractured forms engage the viewer’s mind in puzzle‑like reassembly. This duality—serene yet cerebrally active—exemplifies modernism’s promise to unite feeling and thought. Observers may find themselves both soothed by the painting’s airy expanses and fascinated by its structural intricacies, a testament to Demuth’s skill in harmonizing opposites.

Legacy and Influence

Charles Demuth’s Bermuda works have gained increasing recognition for their role in American modernism’s development. By bringing Cubist fragmentation into the realm of landscape, he anticipated later abstractionists who would probe the boundaries of representation and pure form. His emphasis on geometry, light, and negative space resonates in mid‑century art movements, from Color Field painters to Minimalists exploring the interplay of void and presence. Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House thus occupies a crucial place in art‑historical narratives, demonstrating how an American artist synthesized international avant‑garde techniques with local subject matter to create a distinctive modernist idiom.

Conclusion

Bermuda No. 1, Tree and House stands as a luminous example of Charles Demuth’s mature modernism. Through a delicate balance of precise pencil structure and ethereal watercolor planes, he transforms a simple island tableau into an intricate dialogue between geometry and nature. The painting’s graceful fragmentation, harmonious palette, and open composition invite viewers into a meditative space where form and void, humanity and environment, converge. As part of Demuth’s Bermuda series, this work illuminates his capacity to adapt avant‑garde strategies to new contexts, shaping a lasting legacy in American abstract art.