Image source: artvee.com

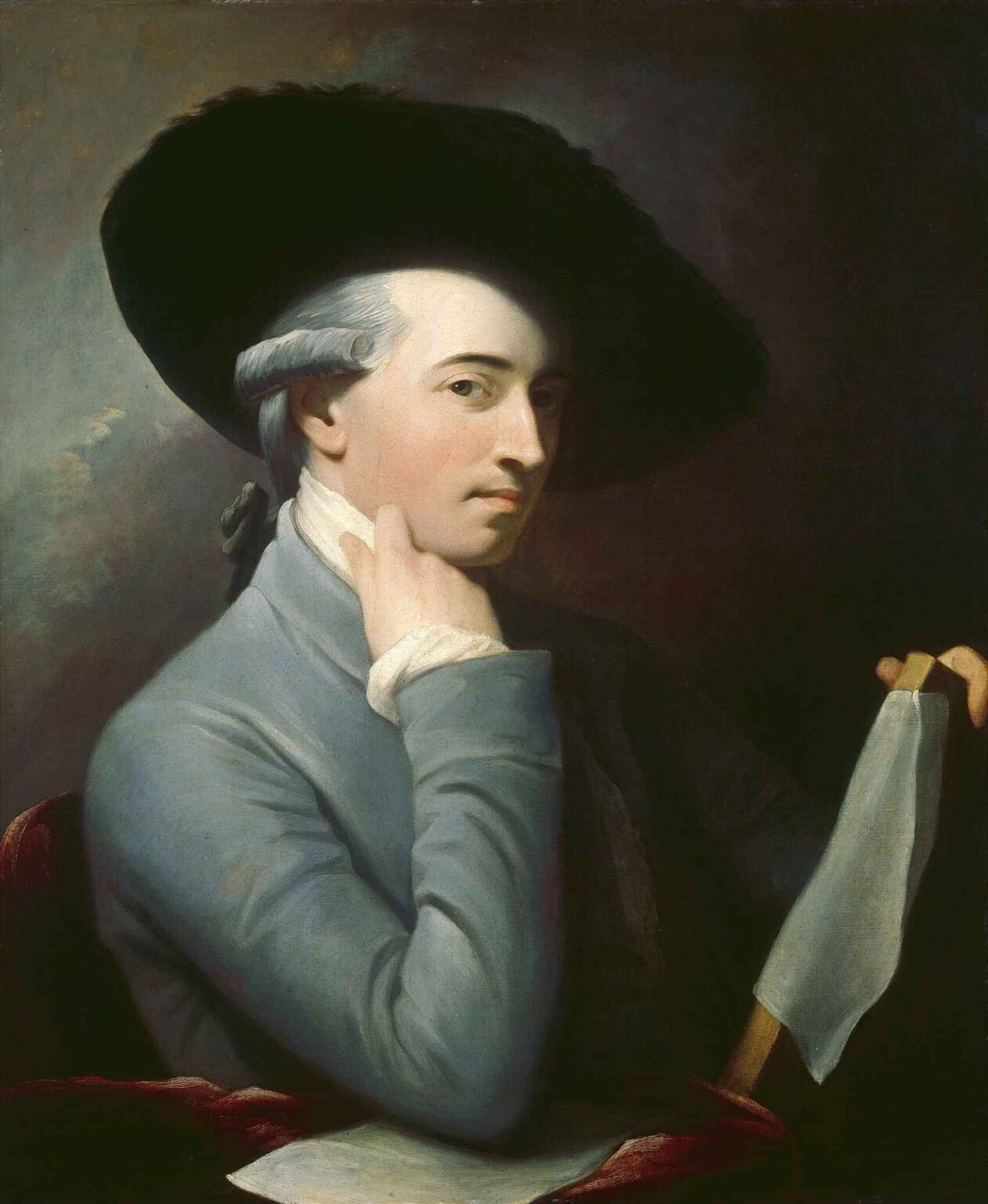

The 18th-century painting Benjamin West Portrait, painted by the artist himself in 1776, is a fascinating window into both the stylistic ambitions and self-perception of one of the most pivotal figures in Anglo-American art history. Known for his grand history paintings and role as the second president of the Royal Academy in London, Benjamin West was a key figure in the cultural development of both Britain and the early United States. Yet in this intimate and carefully crafted self-portrait, we encounter a very different West: not the monumental painter of epic subjects, but a thoughtful, composed gentleman artist—ambitious, intellectual, and subtly self-assured.

This analysis will explore the composition, style, symbolism, and historical significance of this portrait, emphasizing how West’s painting serves as both a personal image and a broader cultural statement. By analyzing pose, color, costume, and context, we’ll see how this painting fits into the artistic and political landscape of 1776—a momentous year in both West’s life and Western history.

The Historical Context: A Portrait in a Year of Revolution

To begin, it’s important to note the year of the painting: 1776. This was not only the year of American independence but also a period of personal maturity and professional recognition for Benjamin West. Though American-born (in Springfield, Pennsylvania, in 1738), West had by this time been residing in London for over a decade, having won favor with King George III and become a dominant presence at the British court. Despite his colonial roots, West aligned himself with the British art establishment, seeking to elevate historical painting as the highest form of artistic expression.

This self-portrait, created at the height of his fame, is thus more than a simple likeness. It is an assertion of identity, positioning West as both a refined intellectual and a transatlantic artistic authority at a time when the Atlantic world was being radically reshaped.

Composition and Pose: Reserved Authority

In the portrait, West is shown in a seated position, his body turned slightly to the viewer’s right, while his gaze is directed at us with calm self-possession. He rests one hand on his neck in a gesture that is both thoughtful and subtly theatrical. His other hand appears to grasp a cane or baton, draped with a cloth—possibly a painter’s mahlstick or a reference to authority.

The tilt of his head and the thoughtful placement of his hand suggest contemplation, artistry, and control. This isn’t the casual, romanticized self-portrait of a bohemian painter; it is the carefully curated image of a gentleman-artist. He wears a powdered wig and black tricorn hat, reinforcing his status and sobriety. His clothing—a blue coat over a high-collared white shirt—is refined but not opulent. The color choices suggest dignity and restraint.

This portrait is composed to communicate West’s dual allegiance to both art and intellect, placing him within the Enlightenment ideal of the learned creator. It is as much an act of branding as it is a record of appearance.

Lighting and Color: Subtle Drama and Depth

West employs a restrained palette dominated by cool grays, soft blues, and deep shadows. The use of chiaroscuro—subtle contrasts of light and shadow—gives the figure a three-dimensional solidity without overt theatricality. The light source comes from the left, softly illuminating West’s face, creating a gentle gradient from forehead to cheek, which lends the painting a classical calmness.

This use of light, typical of late Baroque and early Neoclassical portraiture, reflects West’s academic training and his debt to painters like Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. The background is kept subdued, offering no distractions from the sitter’s presence. The overall tone of the painting is contemplative and measured, mirroring the intellectual persona West sought to cultivate.

The Hat and the Gaze: Visual Authority

West’s large tricorn hat plays a surprisingly significant role in the composition. Its black silhouette occupies much of the upper left quadrant, its shadow enhancing the drama of West’s illuminated face. The hat is not only a symbol of contemporary fashion but also a mark of status—placing West firmly within the class of educated, urbane gentlemen.

His gaze, directed steadily at the viewer, is one of calm observation. There is no overt emotion, no smile, but a confident serenity. In this regard, West is not just presenting himself as a painter, but as a thinker—an intellectual engaged with the viewer in silent dialogue.

This kind of composed gaze was typical of Enlightenment portraiture, aiming to communicate reason, judgment, and inner discipline. West’s expression is not cold, but reserved—a subtle nod to his belief that painting should elevate the soul rather than cater to emotion.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Though minimal in props, Benjamin West Portrait contains subtle references to West’s profession and self-conception. The cloth-draped stick in his right hand might be interpreted as a painter’s mahlstick, suggesting his artistic vocation without explicitly depicting tools or easels. The paper on the table could also suggest intellectual labor—perhaps a sketch, a letter, or a draft of an idea.

These understated symbols contrast with the more overt iconography of many 18th-century portraits, where artists were often surrounded by palettes, brushes, busts, or allegorical references. West’s restraint is a statement in itself: he needs no theatrical props to assert his authority. His very posture, gaze, and dress are sufficient to convey identity.

This decision also reflects West’s belief that art should be noble and refined, aligning with the ideals of Neoclassicism. His painting embodies decorum, intellect, and controlled self-awareness—values central to his theory of history painting.

West’s Artistic Identity: Between Two Worlds

As an American in Britain, West occupied a unique position. He was deeply committed to the Royal Academy and the monarchy, yet he came from a background far removed from aristocratic privilege. His rise to prominence symbolized the potential for merit-based success, especially in a time when national identity and social class were being redefined.

This self-portrait subtly reinforces that dual identity. It reflects West’s aspiration to be accepted not only as a successful painter but as a cultural figure—a bridge between New World ambition and Old World tradition. In portraying himself with poise and simplicity, West asserts his belonging in the intellectual elite of both Britain and America.

It’s no coincidence that 1776, the year of this portrait, was also the year of the American Declaration of Independence. West, living in London at the time, did not return to America during the Revolution, but remained an important figure for American artists abroad. This painting, then, exists at a crossroads: a visual record of personal success during a time of historic rupture.

Technique and Style: Classical Clarity

West’s handling of paint is smooth and controlled, with little visible brushwork. This classical approach was consistent with academic training and the expectations of elite portraiture in the 18th century. His skin tones are modeled with delicacy, and the fabric of the clothing is rendered with a softness that avoids both stiffness and excessive detail.

There is no decorative flourish for its own sake; everything serves the goal of psychological realism and refined presentation. The crisp line of the collar, the soft fold of the cravat, the sheen on the coat—each element reinforces the sitter’s dignity without drawing undue attention.

This approach also mirrors West’s broader goals as a history painter. He sought to bring grandeur and seriousness to modern subjects, often drawing inspiration from ancient Rome and the Renaissance. In this self-portrait, we see those same ideals translated into personal expression.

Legacy and Significance

Benjamin West Portrait is more than a personal likeness—it is a strategic and symbolic self-representation of one of the 18th century’s most influential artists. West used portraiture not only to preserve appearance but to project values: rationality, restraint, intellect, and professionalism. At a time when the artist’s role in society was still evolving, West presents himself not as a craftsman, but as a cultural figure equal to philosophers, poets, and statesmen.

This portrait also serves as an important example of how American artists abroad navigated their identities during a time of national upheaval. West’s calm demeanor and English attire might seem at odds with the revolutionary fervor of 1776, but they reflect a different kind of revolution: one grounded in artistic elevation, transatlantic dialogue, and the quiet assertion of excellence.

Conclusion: A Gentleman’s Vision of the Artist

Benjamin West Portrait is a masterclass in subtlety. Through carefully constructed composition, controlled lighting, and symbolic restraint, West offers an image of the artist as gentleman, thinker, and cultural architect. It is a self-portrait rooted in Enlightenment ideals—where reason, decorum, and personal refinement matter as much as technical skill.

In a world that was changing rapidly—politically, culturally, and philosophically—West carved out a visual identity that bridged continents and defined artistic professionalism for generations to come. This painting, modest in format but profound in meaning, stands as a quiet manifesto for what it meant to be an artist in the Age of Reason.