Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

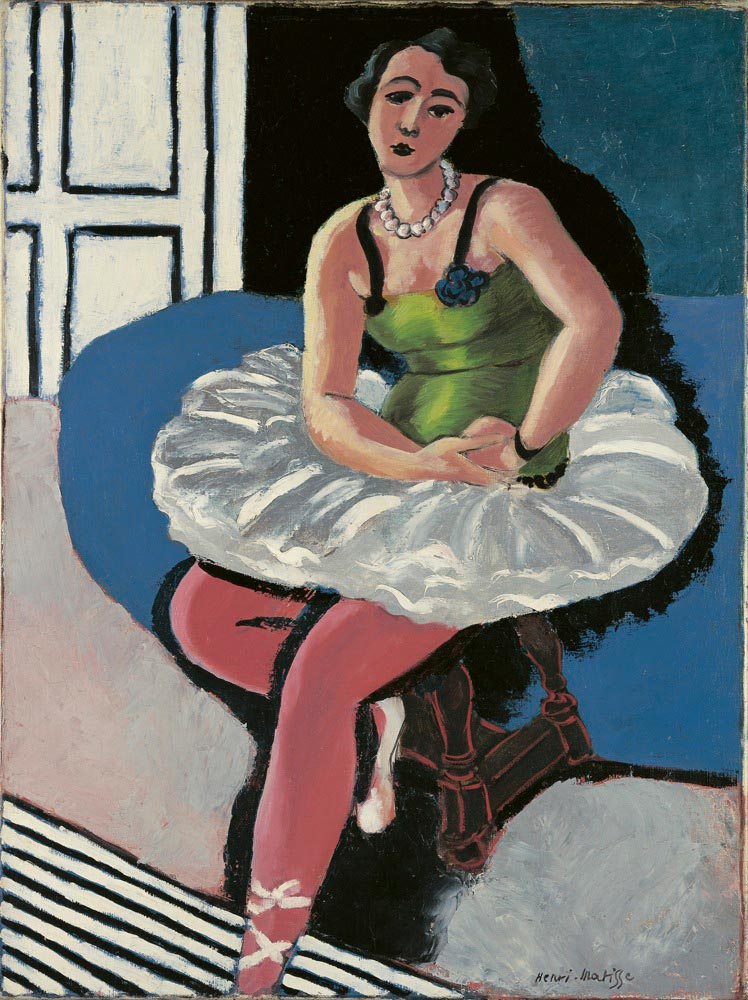

Henri Matisse’s “Ballet Dancer Seated on a Stool” (1927) distills the Nice period into a crisp, theatrical interior where color, contour, and pose collaborate with unusual directness. A young dancer, wearing a green bodice, white tutu, and rose-pink tights, sits slightly forward on a carved stool. Around her, large planes of black, blue, and pale gray stage the figure with almost architectural clarity. The tutu radiates in chalky arcs; the tights sweep in a single diagonal; the pearl necklace and silken rosette place bright, punctual notes near the head and breast. Matisse’s ballet subject is not a narrative vignette but an orchestration of relations: circular against linear, warm against cool, and soft fabric against hard furniture and floor. The picture holds the simplicity of a poster and the depth of a chamber score.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Turn

By the late 1920s Matisse had moved beyond Fauvism’s shout into a modern classicism that favored measured intervals and long, breathable chords of color. Working in the luminous climate of the Riviera, he arranged small rooms as portable theaters, using screens, patterned floors, and a handful of furniture to test how color could function as structure. This canvas belongs to the same family as his odalisques and seated women, but the ballet theme introduces a new register: the studio becomes rehearsal space, and costume becomes a study in volume and line. The dancer’s presence is not the pretext for virtuoso anatomy; it is the axis around which the decorative field—large planes, strong borders, select accents—finds equilibrium.

Composition As A Theatre Of Planes

The composition is built from a few decisive planes. A deep black rectangle behind the sitter functions like a proscenium void, throwing the light body forward. To the left, white door panels with black mullions supply a graphic counterweight, and to the right a slab of saturated blue builds a side wall that cools the palette and increases spatial pressure. The floor is a pale, chalky gray that turns into a black-and-white striped rug at the lower left, introducing a kinetic rhythm. The dancer’s tutu forms the painting’s central ring: a frothy disc whose scalloped edge slices into the black and blue like a cloud crossing geometry. Below it, the diagonal of pink tights cuts from upper right to lower left, guiding the eye toward the striped rug, then back along the stool’s legs to the dancer’s clasped hands. It is a composition that reads at a glance and rewards prolonged looping.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color does the architectural work in this interior. The black field creates depth and carves a silhouette around head, shoulders, and tutu; the blue plane on the right is a cool wall that keeps the overall chord from overheating; the door’s stark white sets a high key that then reappears in tutu, pearls, and slipper ribbons. The green bodice forms the hinge between warm and cool: not a pure emerald but a range of olive and sap modulated by shadow and reflected light. The pink tights provide the major warm accent, their rosiness moving through slightly cooler and warmer passages as the leg rounds or recedes. Because each hue borrows from its neighbor—green picking up blue near the shadow edge, white tutu absorbing pale lavender where it turns—the palette breathes rather than locks, and the dancer’s presence feels embedded rather than pasted onto the set.

Pattern, Rhythm, And The Disciplined Decorative

Matisse keeps pattern scarce and strategic so that rhythm remains legible. The striped rug in the lower left corner acts as a metronome: its black-and-white bars translate the dancer’s diagonal into a measured beat. The tutu’s scallops introduce a contrary meter—small crescents repeating around a circle—which softens the rug’s insistence and breaks the large planes into palatable pulses. The pearl necklace offers a third rhythm: a chain of bright beads that bracket the head and anchor the upper torso to the color field. Nothing is fussy; everything is counted.

The Tutu As Sculptural Ring

The tutu is the picture’s great sculptural event. Matisse paints it not as detail-rich fluff but as a disciplined ring of whites, grays, and pale violets. Short, loaded strokes radiate from the waist and break into scallops at the edge, creating a sense of compressed springs. Where the tutu overlaps the black background it reads brilliantly; where it crosses the blue wall it cools and softens, and where it lies over the dancer’s lap it densifies into a grayish volume. In effect, the tutu is both garment and stage—a portable cloud that contains the figure and sets the tempo for everything around it.

The Figure’s Poise And Modern Agency

Though the subject is ostensibly theatrical, the dancer’s attitude is inward and contemporary. Her head tilts slightly, eyes half-lidded yet direct; the mouth is small, firm, unperformed. Hands rest calmly in the lap, one wrist circled by a dark band that repeats the straps of the bodice. There is no busy gesture; instead Matisse gives us a pause between movements, the stillness that follows a phrase. Agency comes from poise. The dancer holds the center not by demonstrative expression but by the exactness with which her silhouette is set against the architectonic planes.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s contour, as always, confers authority. The chin is a single curve that tightens near the jaw hinge; the nose and mouth are placed with economy; the bodice straps are drawn as unbroken bands that describe shoulder and chest with almost calligraphic weight. The legs, particularly the forward knee, are established with a strong, continuous line that negotiates form by pressure alone. Even the stool is a series of living edges—curved struts and turned legs that avoid mechanical symmetry. These lines don’t imprison color; they give it a resilient boundary. Because the contour breathes, the planes of color can be felt as flesh, cloth, wood, and air without recourse to literal texture.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The painting’s light is diffuse and reflective rather than theatrical. Shadows rarely sink to black; they are chromatic—slate along the tutu’s underside, olive and blue-green in the bodice, rosy-brown where the tights round toward the stool. Highlights are small and exact: a glint on a pearl, a pale stroke on the shoulder, a quick white on the slipper ribbon. This approach keeps value contrasts within a comfortable range so that color can carry volume and the interior’s calm is maintained. The dancer seems illuminated by the room’s surfaces rather than by a single directional lamp, a hallmark of Matisse’s Nice interiors.

The Stool And The Grounding Of Weight

The carved stool grounds the figure physically and pictorially. Its darker russet-brown and black edges supply the deepest notes in the lower half, preventing the pink diagonal from floating. Structurally, the stool’s vertical legs answer the door’s mullions on the left and the implied vertical of the dancer’s torso, while its circular seat echoes the tutu’s ring at a smaller scale. Shadows beneath the seat and between the legs are carefully tuned to the floor’s pale gray so that the sitter’s weight reads convincingly even as the space remains shallow.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Spatially, the picture is compressed by design. The black rectangle behaves like a flat backdrop; the blue wall acts as a single plane; the door’s paneling is a drawing on the surface; and the floor tilts forward, inviting the viewer to the dancer’s feet. Overlaps—tutu across the wall, leg over the stool, slipper against the rug—create just enough depth to persuade the body’s volume. This productive flatness concentrates attention where Matisse wants it: the surface where color meets contour and where relations can be read immediately.

Ballet And Modernism: A Dialogue Of Disciplines

Matisse was attentive to ballet’s modernizing influence in the 1910s and 1920s. What interested him was not romantic narrative but the grammar of movement—clarity of line, sculptural armatures, and the idea of a body as a designed object in space. This painting embodies that dialogue. The tutu reads like a disciplined device, the pose like a rehearsed sentence, the studio like a distilled stage. The artist does with color what choreography does with bodies: sets intervals, balances diagonals, and resolves phrases with rest.

Comparisons Within The Oeuvre

The work converses with the 1925 “Dancer” framed by a red tapestry, but it trims ornament and raises the ratio of plane to pattern. It shares with the seated odalisques a shallow interior anchored by strong upholstery or flooring, yet here the stripes and panels speak more overtly in graphic terms. The black-and-white rug prefigures the radical economy of the late paper cut-outs, where stripes and silhouettes would carry entire compositions. Across these dialogues, the constants remain Matisse’s trust in contour, his use of color as structure, and his insistence that the decorative can be rigorous.

Tactile Intelligence And The Variety Of Touch

Although flatness rules, touch varies. The tutu is built with short, chalky pushes that form a palpable crust; the black wall is brushed in broad, nearly matte sweeps; the blue plane is smoother, carrying a slight sheen that catches light; the tights are painted in long, elastic strokes that follow the leg’s arc; the door panels are laid thinly so ground tone participates. This orchestration of touch persuades the senses without breaking the picture’s graphic unity. You can almost feel satin, tulle, painted plaster, and polished wood, yet nothing dissolves into illusionism.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The dancer’s expression is serene, even slightly introspective. The lowered head, soft mouth, and inward clasp of hands propose a pause in rehearsal rather than spectacle. The surrounding planes respect that mood: the black field quiets the upper half, the blue cools the right side, and the gray floor absorbs sound like studio dust. For the viewer the experience is one of sustained attention. You read the large shapes quickly, then you slow down to notice small harmonies—the green bodice recruiting a cool reflection from the blue wall, a pearl echoing the white panel, a pink highlight answering the stripe on the rug.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Calm

Pentimenti peep through if you look closely: a shift in the tutu’s outer edge, a reinforced line at the forward knee, a corrected angle in the stool’s leg. These adjustments do not agitate the surface; they record the work by which balance was reached. The picture’s serenity is not a given—it is the outcome of revisions that tuned intervals until the figure sat with unforced rightness.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return yields a fresh hinge: a pearl glint aligning with a door panel’s white; a green half-tone cooling where the bodice meets the blue wall; a black contour tightening at the wrist and relaxing along the thigh; a striped rug that catches the pink diagonal and returns it with rhythm. The image never collapses into anecdote. It invites the eye to test and retest the spacing of differences—disc and stripe, warm and cool, stillness and implied movement—finding satisfaction each time.

Conclusion

“Ballet Dancer Seated on a Stool” is a compact manifesto for Matisse’s late-1920s practice. Within a shallow, poster-like stage, he sets a ring of white tulle, a diagonal of pink, a hinge of green, and the clean geometry of black, blue, and white. Color becomes architecture; pattern becomes counted rhythm; contour becomes a breathing boundary. The dancer is not posed for a story but placed for harmony, her calm agency anchoring a room where everything is tuned to her presence. The painting proves that the decorative, in Matisse’s hands, is the very method by which thought takes visible form and pleasure becomes durable.