Image source: artvee.co

Introduction

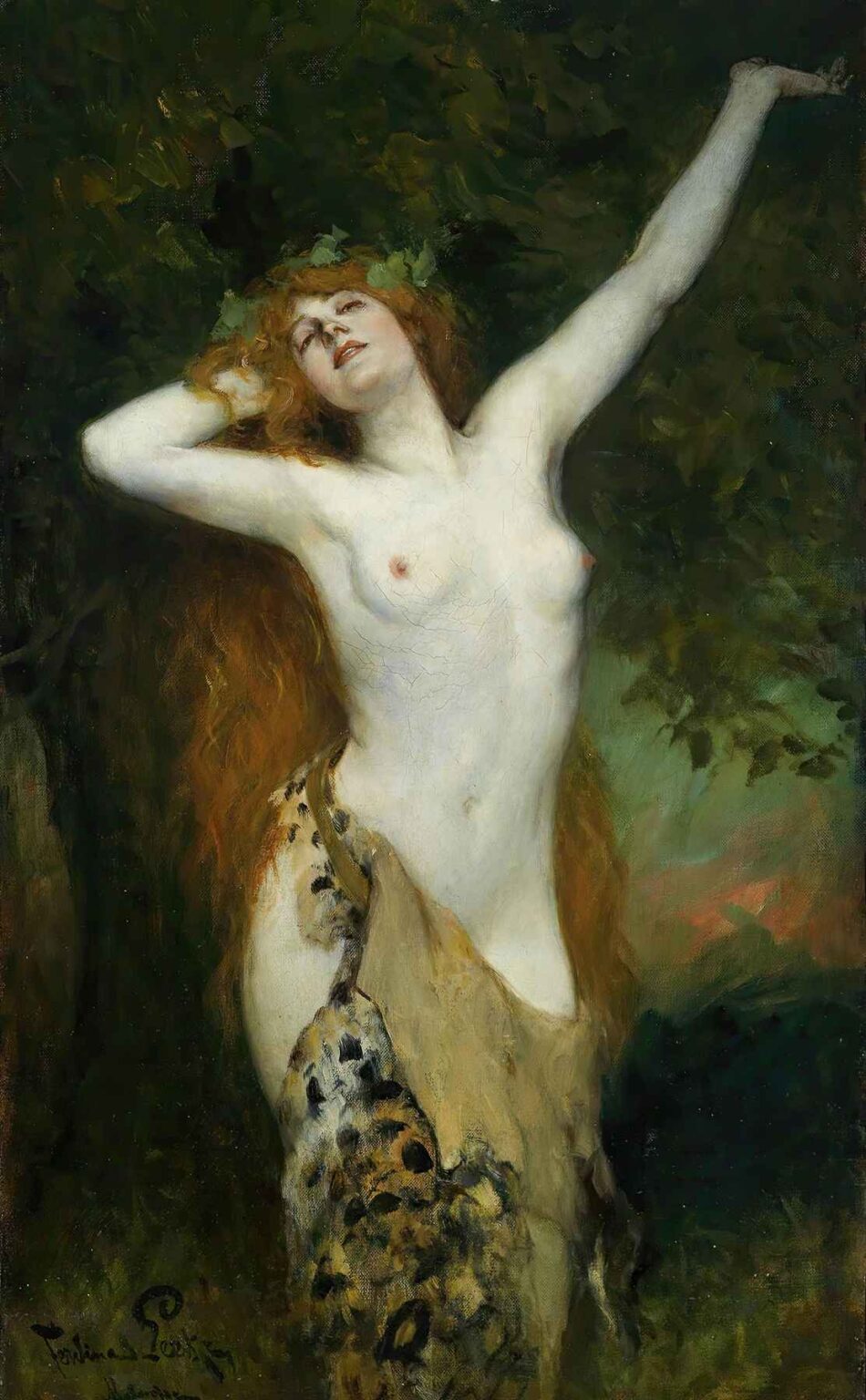

Ferdinand Leeke’s Bacchantin is an evocative celebration of sensuality, nature, and mythological ecstasy. Painted during the late 19th or early 20th century, this luminous and sensuous work captures the spirit of a bacchante—a female follower of Bacchus (Dionysus), the Roman god of wine, revelry, and ecstatic liberation. Blending classical subject matter with the stylistic fluidity of Symbolism and the elegance of German Romanticism, Leeke creates a painting that is both emotionally intense and technically refined.

Though not as universally recognized as some of his contemporaries, Ferdinand Leeke (1859–1937) was a German painter celebrated for his Wagnerian mythological subjects and his sensitive portrayals of classical figures. In Bacchantin, he departs from theatrical narratives and instead offers a deeply personal, almost hypnotic image of a woman in communion with nature and abandon.

This analysis will explore the painting’s mythological roots, composition, lighting, symbolism, emotional tone, and its placement within Leeke’s wider oeuvre and the tradition of fin-de-siècle European art.

Who Are the Bacchantes?

In Greco-Roman mythology, bacchantes (or maenads in Greek) were female devotees of Bacchus/Dionysus. They were known for their ecstatic rituals, wild dancing, and immersion in the natural world. Often portrayed as draped in animal skins and crowned with ivy or grape leaves, bacchantes symbolized both divine inspiration and chaotic liberation from societal constraints.

They appear in literature and art as figures of unrestrained passion and mystic frenzy. Euripides’ The Bacchae offers a dark exploration of their power, while later Romantic and Symbolist artists recast them as muses of erotic and artistic liberation. In Leeke’s Bacchantin, the artist focuses on this latter vision: the bacchante as a vessel of beauty, intoxication, and transcendence.

Composition and Pose

The painting is vertically oriented, emphasizing the upward stretch of the female figure at its center. The bacchante is caught mid-movement, her body arched with arms raised in rapture or surrender. Her head is tilted back, lips parted, and eyes half-closed in a state of ecstatic bliss. The movement is not violent or frenetic—it is sensual, fluid, and lyrical.

Her entire posture embodies release. One arm lifts skyward while the other cradles her flowing red hair. Her chest is exposed, but rather than being objectified, it reads as an expression of vulnerability and divine communion. Draped loosely around her hips is a leopard skin—an attribute closely associated with Dionysus, who was often depicted riding a leopard or wrapped in its pelt.

The background is composed of soft green foliage and earth tones, blurring the line between body and landscape. The overall effect is a feeling of immersion—this is not a staged scene, but an intimate moment of union with nature.

Light and Color

Leeke uses light with dramatic restraint. The bacchante’s pale skin glows against the dark, leafy backdrop. She becomes a beacon within the shadowy forest, illuminated as though by the setting sun or an otherworldly light. This chiaroscuro effect enhances the mystical aura of the figure, giving her a near-supernatural presence.

The palette is dominated by natural earth tones: deep greens, rich browns, and amber-gold highlights. These hues echo the wilderness of Dionysian ritual, while the occasional hints of red in the lips, cheeks, and background add sensual warmth.

The texture of the skin is rendered with extraordinary delicacy—soft, luminous, almost iridescent. Meanwhile, the leopard pelt offers a tactile counterpoint: rough, spotted, and sinuous. The combination of textures reflects the union of the animal and divine, instinct and transcendence.

Symbolism and Allegory

Bacchantin functions as both a mythological image and an allegorical meditation. The bacchante is not simply a character from ancient lore—she is a symbol of human ecstasy, freedom from repression, and the sacred feminine.

The upward gesture of the figure suggests transcendence or invocation. Her ivy crown, traditional in depictions of Bacchus and his followers, symbolizes fertility, intoxication, and eternal life. Ivy is an evergreen—resilient, clinging, enduring—making it an apt emblem for the persistent pull of passion and instinct.

The leopard skin is one of the painting’s most potent symbols. In antiquity, the leopard was associated with untamed nature and divine possession. To wear its pelt was to align oneself with the wild and the unknowable. In this painting, the bacchante wears it almost casually, suggesting her full embrace of the Dionysian principle.

Taken together, the symbols evoke a vision of liberation—not merely from societal norms, but from internal constraint. The bacchante embodies a return to elemental being, a life lived in ecstatic harmony with the rhythms of nature.

Emotional Resonance

One of the most powerful aspects of Bacchantin is its emotional directness. The viewer is not kept at a distance—Leeke’s composition invites intimacy, empathy, and even identification. The figure’s expression is ambiguous: is it joy, sorrow, madness, or divine inspiration? The openness of interpretation is one of the work’s greatest strengths.

There is no irony, no cynicism—only a sincere portrayal of surrender. Unlike more voyeuristic treatments of the nude, this painting does not invite objectification. Instead, it renders the female body as a site of revelation and transformation.

This emotional sincerity situates Bacchantin within the broader Symbolist movement, which sought to transcend material reality and access the inner truth of experience through suggestion, mood, and myth.

Ferdinand Leeke’s Artistic Background

Ferdinand Leeke was a German painter educated at the Munich Academy. He became particularly well known for his illustrations of Richard Wagner’s operas, producing a celebrated series of paintings that visualized key moments from The Ring Cycle and other mythic tales. His style combines romantic historicism with a keen sensitivity to psychological nuance.

While his Wagnerian works are more narrative and theatrical, Bacchantin reveals a more poetic, intimate side of Leeke. Here, the myth is not enacted as story but invoked as presence. It’s less about narrative progression than about emotional immersion.

Leeke’s ability to render flesh, light, and atmosphere places him in the company of artists like Franz von Stuck and Arnold Böcklin, who similarly balanced mythological themes with Symbolist mood.

Feminine Archetypes in Fin-de-Siècle Art

At the turn of the 20th century, the figure of the femme fatale, the mystic muse, and the liberated goddess became central archetypes in European art. Artists like Gustav Klimt, Fernand Khnopff, and Edvard Munch explored the feminine as both divine and dangerous, sacred and erotic.

In this context, Leeke’s Bacchantin emerges not as an isolated image but as part of a wider cultural conversation. The bacchante represents the feminine principle unchained—fertile, intuitive, wild, and transcendent. She is not a moral warning or romantic fantasy but an embodiment of nature’s eternal cycle of death and renewal.

Unlike the femme fatale, who often destroys, the bacchante is generative. She loses herself not in manipulation but in the joy of being. Her power is not weaponized—it is elemental.

The Nude as Ecstasy, Not Eroticism

While the subject is a nude woman, Bacchantin avoids the pitfalls of mere titillation. The nudity here is natural, contextual, and integral to the subject matter. The bacchante’s lack of clothing symbolizes her renunciation of artifice and her union with primal forces.

Her pose—arched, lifted, open—is one of expansion, not seduction. She is not presented for the viewer’s consumption but for her own awakening. In this sense, the painting aligns with Symbolist efforts to restore spiritual significance to the body and sensual experience.

This approach also echoes classical traditions, where the human body was a site of divine manifestation rather than shame or temptation. Leeke’s bacchante is a modern heir to that lineage—timeless, radiant, and free.

Reception and Legacy

Ferdinand Leeke’s works have remained somewhat underappreciated compared to more canonized figures of German Romanticism and Symbolism. However, in recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in artists who operated at the intersections of mythology, emotion, and Symbolist aesthetics.

Bacchantin is a testament to Leeke’s sensitivity, his technical prowess, and his ability to distill complex emotional and mythological ideas into a single figure. The painting resonates with contemporary audiences for its exploration of liberation, embodiment, and emotional surrender.

As feminist and post-symbolist readings of art history continue to expand, Bacchantin finds new relevance—not as a relic of outdated myth, but as a visionary portrayal of spiritual and physical freedom.

Conclusion

Ferdinand Leeke’s Bacchantin is a luminous, emotionally rich painting that captures the essence of mythic ecstasy. Through its poetic composition, symbolic imagery, and reverent depiction of the female form, it celebrates the power of passion, nature, and transcendence.

Far more than a decorative nude, this bacchante invites the viewer into a sacred space of release and renewal. She stands not as an object, but as an archetype—an image of what it means to be alive, wild, and whole.

Leeke’s Bacchantin continues to captivate modern audiences not only for its technical beauty, but for the timeless truth it reveals: that within each of us lies the capacity for rapture, for surrender, and for union with something greater than ourselves.