Image source: artvee.com

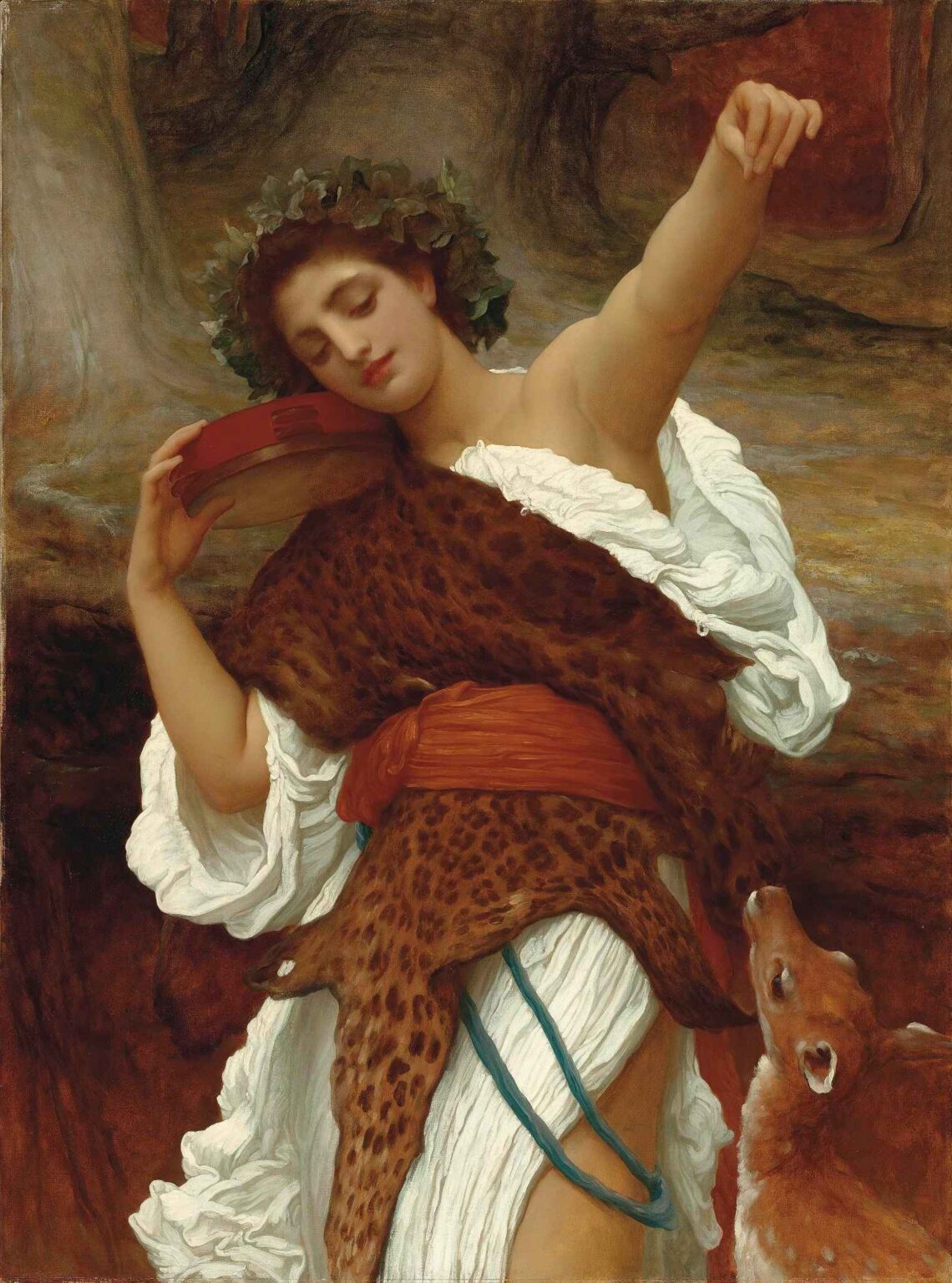

Frederic Leighton’s Bacchante is a masterful example of late 19th-century Academic painting, combining classical mythological subject matter with sensuality, psychological depth, and technical refinement. Created by the renowned Victorian painter and sculptor Frederic Leighton, 1st Baron Leighton (1830–1896), Bacchante depicts a female devotee of Bacchus—the Roman god of wine, ecstasy, and divine frenzy. Dressed in swirling white robes and crowned with ivy, the Bacchante sways rhythmically to a music we cannot hear, her eyes gently closed, and a red tambourine resting against her cheek.

This in-depth analysis of Bacchante explores its mythological context, visual composition, symbolism, technical brilliance, and the cultural environment in which it was produced. As both an embodiment of beauty and a vehicle for timeless archetypes, Leighton’s painting continues to captivate viewers with its ethereal mood and sublime execution.

Historical and Artistic Context

Frederic Leighton was one of the most important figures of the Victorian art world. A celebrated member of the Royal Academy and later its president, he was also a key participant in the Aesthetic Movement—an artistic and literary movement that emphasized beauty, form, and emotional resonance over moral or narrative content.

Painted in the 1890s, Bacchante falls within a period of Leighton’s oeuvre that is deeply invested in mythological themes and classical subjects. This interest was not merely antiquarian; it reflected broader 19th-century anxieties about modernity, spirituality, and the role of sensual experience in human life. For Leighton and many of his contemporaries, classical mythology offered a means to explore the human psyche, often through veiled eroticism and emotional suggestion.

The figure of the Bacchante, or Maenad in Greek tradition, was especially potent. Bacchantes were the frenzied female followers of Bacchus (or Dionysus), known for their ecstatic dances, ritual intoxication, and symbolic association with nature and freedom. In Bacchante, Leighton interprets this figure not as a wild creature in the throes of madness, but as an elegant, introspective ideal—imbued with grace, rhythm, and transcendence.

Composition and Form

The composition of Bacchante is vertically elongated, enhancing the elegance and flowing movement of the central figure. The Bacchante is positioned slightly off-center, her upper body curving leftward in a rhythmic arc that is mirrored by her raised arm and the crescent shape of the tambourine. Her eyes are closed, suggesting inward ecstasy, and her expression is serene, poised between consciousness and dream.

She is crowned with ivy, a traditional symbol of Bacchic worship, which frames her face with natural grace. Her garment is a luminous white robe with classical drapery, rendered in soft, voluminous folds. The robe slips off her shoulders to reveal a leopard skin draped diagonally across her torso—a signature attribute of Bacchic iconography, symbolizing the primal, untamed nature of the cult of Dionysus.

The lower right corner of the painting features a small deer, gently nuzzling the hem of her robe. This creature deepens the natural symbolism, linking the Bacchante with woodland freedom and divine harmony with animals. The interaction between woman and animal also serves as a nod to the mythic wilderness where Bacchic rites were said to take place.

Use of Color and Light

Leighton’s color palette in Bacchante is both restrained and strategic. The warm earth tones of the background, with its muted browns and ochres, set off the figure’s luminous white robe and alabaster skin. The tambourine, a vivid red, becomes a focal accent—echoing the red sash that cinches the leopard skin at her waist and suggesting the passion and intensity of the Dionysian cult.

Light in the painting is soft and diffused, falling from the upper left to gently model the Bacchante’s face, shoulder, and raised arm. The subtle gradation of light across her body accentuates the texture of the fabrics and the warmth of her complexion. Her skin glows with a kind of idealized vitality, neither overly real nor overly abstract.

The leopard skin, in particular, is painted with remarkable attention to detail. Its pattern is tactile and lifelike, contrasting sharply with the ethereal quality of the drapery and skin. This juxtaposition of textures—rough animal pelt, smooth skin, and airy cloth—heightens the painting’s sensual complexity.

Symbolism and Allegory

Bacchante is rich with symbolic meaning, much of it drawn from Greco-Roman mythology and the visual traditions of the European academic canon.

The Bacchante Herself: In classical mythology, Bacchantes (or Maenads) were female devotees of Bacchus, god of wine and ecstasy. Often portrayed in a state of divine madness, they represented freedom from social norms and rational constraints. However, Leighton’s Bacchante is not overtly frenzied; instead, she embodies a refined and inward version of ecstasy—a state of divine harmony and elevation.

Ivy Wreath: The wreath adorning her head is made of ivy, a sacred plant of Dionysus. Ivy symbolized eternal life and divine intoxication. In Victorian art, it also carried connotations of fidelity and poetic inspiration.

Tambourine: The tambourine is both a musical instrument and a symbol of ritual. In Bacchic rites, it was used to invoke rhythmic trance and ecstatic dance. Here, it rests quietly against the Bacchante’s cheek, suggesting a moment of calm after ecstasy, or perhaps a reverie in anticipation of it.

Leopard Skin: The presence of the leopard skin is a direct allusion to Bacchus, who was often depicted riding or accompanied by leopards. It symbolizes the untamed, carnal energy of the god. Draped across the woman’s soft form, it hints at the duality of civilization and savagery, restraint and desire.

The Deer: The small deer nestled at the bottom right of the painting evokes innocence, gentleness, and natural harmony. In Dionysian myth, deer were sacred animals, associated with both sacrifice and serenity. The creature’s gaze toward the Bacchante may represent nature’s recognition of her divine role.

Thematic Resonance: Ecstasy, Femininity, and Idealization

One of the most powerful themes in Bacchante is the exploration of feminine ecstasy—not in its chaotic form, but as a controlled, internalized experience of transcendence. Leighton’s woman is not overtaken by frenzy, but rather suspended in a dreamlike state of self-contained pleasure. Her closed eyes, raised arm, and delicate posture all communicate surrender without collapse—power without aggression.

This idealized femininity reflects Victorian ideals about beauty, modesty, and the “danger” of unleashed passion. Leighton, however, resists moralizing. He presents sensuality and mysticism not as opposites, but as interwoven strands of human experience. The Bacchante becomes an archetype of spiritual intoxication—elevated, not degraded, by her divine association.

The painting also explores the duality of man and nature, rationality and instinct. The forest setting, the animal companions, and the goddess-like woman all suggest a return to the primal, but under the guiding hand of beauty and art. In this sense, Bacchante is not a warning against passion, but a celebration of its sublimated form.

Technical Execution and Academic Style

Leighton was known for his rigorous academic training and technical discipline, qualities that are fully evident in Bacchante. His brushwork is smooth and polished, eliminating visible strokes in favor of seamless transitions. This lends the painting a sense of idealized perfection that aligns with classical ideals.

The anatomical accuracy of the Bacchante’s body, the careful rendering of fabric and animal skin, and the harmonious integration of figure and background all reflect Leighton’s mastery. His ability to suggest movement through pose and gesture—without any real action—reveals a deep understanding of classical sculpture and compositional flow.

Moreover, the painting exhibits the hallmarks of the Aesthetic Movement, which emphasized “art for art’s sake.” There is no didactic message here, no overt morality tale—only the celebration of beauty, form, and emotion for their own sake.

Cultural Significance and Reception

In the decades following its creation, Bacchante was admired for its grace and technical brilliance, though sometimes critiqued for its perceived lack of narrative intensity. However, modern audiences have re-evaluated the painting as a subtle meditation on desire, identity, and the boundaries between the divine and the human.

The painting aligns with other works by Leighton—such as Flaming June and The Daphnephoria—in its depiction of women as both aesthetic subjects and spiritual symbols. It also fits within a broader Victorian fascination with classical mythology as a way of engaging with modern ideas of psychology, gender, and the unconscious.

Today, Bacchante remains a significant example of late Academic painting, appreciated not only for its sensual beauty but for its philosophical and symbolic depth.

Conclusion: Beauty in Stillness, Ecstasy in Restraint

Frederic Leighton’s Bacchante is a powerful exploration of classical beauty, mythological resonance, and feminine spirituality. Through its harmonious composition, symbolic richness, and technical precision, the painting draws the viewer into a world where passion is sublimated into art, and ecstasy takes the form of quiet reverie.

The Bacchante, crowned with ivy and wrapped in both silk and fur, stands at the threshold between human and divine, nature and culture, motion and stillness. She invites the viewer not into frenzy, but into contemplation—a rhythmic state of inward transformation. In doing so, Leighton offers a vision of art that elevates, refines, and reveals the soul through the body.