Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

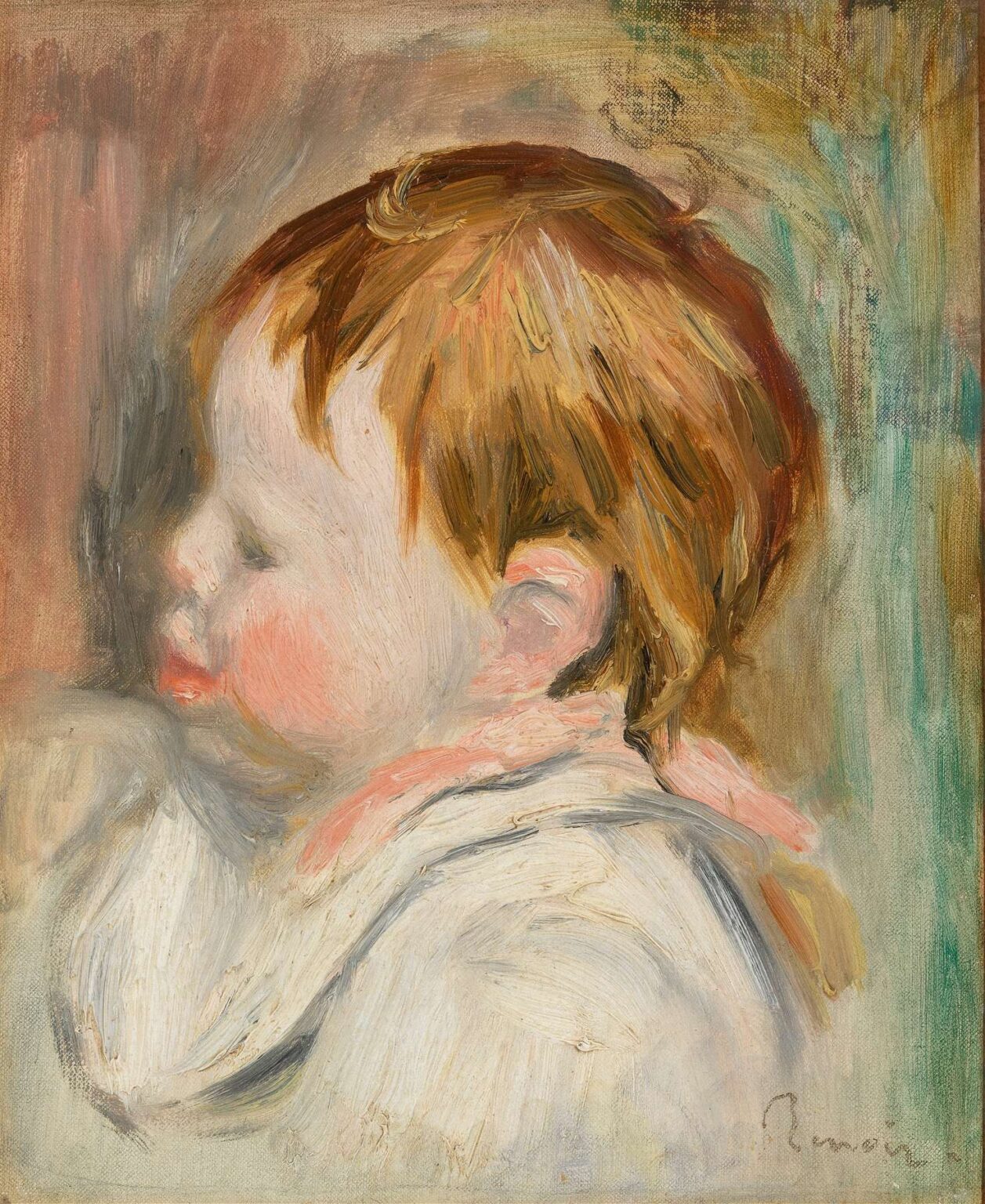

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Baby’s Head (Tête d’enfant, profil à gauche) (1895) offers a tender glimpse into the artist’s late portraiture, where Impressionist spontaneity converges with a deep empathy for his subject. Executed in oil on canvas, this intimate study captures the profile of an infant’s head turned to the left, rendered in soft, luminous brushstrokes. The painting transcends mere likeness to evoke the universal wonder of early childhood and the ephemeral beauty of youth. Through a detailed exploration of composition, color, technique, and emotional resonance, this analysis will illuminate how Renoir transforms a simple portrait into a masterpiece of sensitivity and painterly grace.

Historical and Artistic Context

By the mid‑1890s, Renoir had evolved from his pioneering role in the Impressionist movement toward a more classicizing style, often termed his “Ingres period.” While he retained the vibrant palette and loose handling of paint that characterized his early work, he increasingly emphasized line, form, and a controlled modeling of flesh. Baby’s Head emerges from this mature phase, reflecting both his continued fascination with capturing the effects of light on surfaces and his desire to imbue portraiture with a timeless quality. The painting also belongs to Renoir’s broader interest in children as subjects—an interest he shared with contemporaries yet made uniquely his own through his characteristic warmth and softness of touch.

Subject Matter and Significance

The subject of Baby’s Head is deliberately simple: an infant’s head in profile, free of distracting ornament or setting. By isolating the child’s visage against a loosely rendered background, Renoir directs the viewer’s full attention to the subtle interactions of light, color, and form on the baby’s features. The painting neither identifies the child by name nor situates him within a specific narrative, instead celebrating the universal innocence and freshness of early life. In doing so, Renoir invites viewers to contemplate the fleeting wonder of infancy and the dignity inherent in every human face, no matter how young.

Composition and Framing

Renoir employs a tight compositional frame, cropping the canvas so that the child’s head and upper shoulders fill nearly the entire space. This close perspective creates an immersive experience: the viewer feels drawn into the intimate aura of the baby’s presence. The profile orientation, with the face looking toward the left edge, introduces a gentle directional tension, as if the child is gazing toward an unseen world beyond the canvas. The slight tilt of the head downward conveys a sense of peaceful repose or introspection, heightening the portrait’s emotional impact. By eschewing extraneous details, Renoir ensures the composition remains focused, serene, and profoundly direct.

The Language of Color

A hallmark of Renoir’s late style is his nuanced color harmonies. In Baby’s Head, he employs a restrained yet luminous palette dominated by creamy whites, rosy pinks, and warm flesh tones for the skin, contrasted with subtle ochres and soft greys in the background and the infant’s hair. The delicate application of pink on the cheeks and lips suggests the vibrancy of youthful circulation and health. The hair, painted with quick, confident strokes of golden brown and burnt sienna, captures the fine, downy quality of baby hair. Background hues—muted greys and pale greens—serve to complement the warmth of the flesh tones without competing for attention. This orchestration of color reinforces the painting’s overall harmony and sense of quiet intimacy.

Brushwork and Painterly Technique

Renoir’s handling of paint in this work is at once fluent and disciplined. In the baby’s hair, he applies paint in short, directional strokes that mimic the natural flow of fine strands. On the face and neck, broader, blended passages of paint create a velvety smoothness, conveying the suppleness of infant skin. The background is built up through loose, vertical and diagonal strokes that suggest an abstracted space rather than a literal setting. Through this varied brushwork, Renoir achieves a dynamic surface texture that rewards close viewing: one senses both the artist’s hand in each mark and the overall unity of the painted form. The visible brushstrokes remind viewers of the work’s materiality while serving the illusion of flesh and light.

Modeling of Form and Light

In contrast to the more fractured light of early Impressionism, Baby’s Head exhibits a controlled, even illumination that softly wraps around the features. Highlights across the forehead, nose bridge, and cheekbone are subtle yet sufficient to define the profile. Shadows under the chin and behind the ear are handled with muted greys and lavender tones, lending depth without harsh contrast. This gentle modeling underscores Renoir’s reverence for classical form: the head emerges as a sculptural volume, anchored in space. The nuanced interplay of light and shadow conveys a sense of three‑dimensional presence, allowing viewers to imagine the warmth and texture of the child’s skin under their fingertips.

Emotional Resonance and Intimacy

Beyond technical mastery, Baby’s Head exudes a profound emotional warmth. The child’s closed eyes and slightly parted lips suggest a moment of restful contemplation, perhaps even slumber. This state of vulnerability heightens the portrait’s tenderness: the viewer is granted access to a private, unguarded moment. Renoir’s affectionate rendering of the infant’s features—his soft curves, delicate nose, and faint flush of color—conveys a loving gaze. The painting thus functions as an act of devotion, reflecting the universal bond between caregiver and child. It reminds us of art’s capacity to capture fleeting moments of human connection and to preserve them in timeless form.

Relation to Renoir’s Broader Portraiture

Renoir painted many portraits throughout his career, from large ceremonial commissions to intimate studies of friends and family. His portraits of children, however, hold a distinctive place within his oeuvre: they combine his early Impressionist fascination with outdoor light and color with a later focus on form and tactile presence. Compared to his larger group scenes or elegantly dressed sitters, Baby’s Head feels more personal and unguarded. The painting’s modest dimensions and singular focus reflect Renoir’s mature belief that even the smallest subjects deserve monumental treatment. Through these child portraits, he celebrated innocence, growth, and the human potential for joy.

Symbolism of Childhood and Innocence

In art history, the infant’s visage often symbolizes purity, potential, and new beginnings. Renoir’s Baby’s Head participates in this tradition while avoiding overt allegory. The painting does not depict a religious Madonna and Child but rather a secular, human moment of quietude. The lack of symbolic props or ornate costume grounds the work in reality while leaving room for universal interpretation. Viewers may see in the child’s face an emblem of hope, a reminder of life’s cyclical renewal, or simply a celebration of sensory beauty. Renoir’s genius lies in elevating an ordinary subject to the level of mythic resonance through the power of paint.

The Portrait’s Scale and Viewing Experience

The intimate scale of Baby’s Head encourages close, contemplative viewing. Unlike monumental portraits that demand distance, this canvas invites the observer to approach, to study the subtle variations of tone and texture. The personal viewing experience mirrors the intimacy of the subject’s moment. The small size fosters a one‑on‑one encounter, fostering empathy and identification. In galleries, viewers often pause before this work, sensing its hushed atmosphere despite the subdued color contrasts. Renoir’s decision to render such a delicate subject at this scale reflects his confidence in painting’s ability to engage hearts as well as eyes.

Technical Considerations and Conservation

Executed in oil on canvas, Baby’s Head demonstrates Renoir’s adept manipulation of pigment and medium. Examination of the surface reveals layering of thin glazes in flesh areas, permitting underlying warm undertones to shine through. Impasto accents—especially in the hair and along the collar—provide tactile highlights. Over time, crackle patterns may have emerged, but careful conservation has preserved the painting’s original vibrancy. The canvas stretcher and period‑appropriate framing contribute to the work’s overall presentation, enhancing its historic authenticity. Technical analyses confirm Renoir’s consistent brush handling during this late period.

Reception and Critical Legacy

When first exhibited, Renoir’s late portraits received mixed reviews: some critics longed for the dynamic light of his early Impressionism, while others applauded his return to classical values and expressive warmth. Over the 20th century, art historians have come to appreciate Baby’s Head as a key example of Renoir’s mature vision. Scholars note how the painting encapsulates both the spontaneity of direct observation and the discipline of form. Its emotional resonance has secured its place in major museum collections, where it continues to inspire viewers and artists alike with its timeless portrayal of childhood.

Influence on Subsequent Generations

Renoir’s sensitive studies of children influenced generations of portrait painters who sought to balance technical virtuosity with emotional depth. His ability to evoke the innocence and vulnerability of youth without pandering to sentimentality set a standard for modern portraiture. Artists working in the 20th century and beyond have cited his brushwork and color harmonies as guiding examples for capturing the subtle complexities of human flesh and expression. In this sense, Baby’s Head serves not only as a document of Renoir’s personal evolution but also as a touchstone for the broader trajectory of modern figurative art.

Conclusion

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Baby’s Head (Tête d’enfant, profil à gauche) stands as a testament to the artist’s lifelong commitment to celebrating human beauty in all its stages. Through masterful color harmonies, sensitive brushwork, and an unwavering gaze of affection, Renoir elevates a simple infant portrait to the realm of poetic art. The painting’s intimate scale, harmonious composition, and emotional depth invite viewers into a shared moment of wonder at life’s early mysteries. More than a study of a child’s visage, Baby’s Head remains a timeless meditation on innocence, vulnerability, and the power of paint to capture the fleeting grace of human existence.