Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

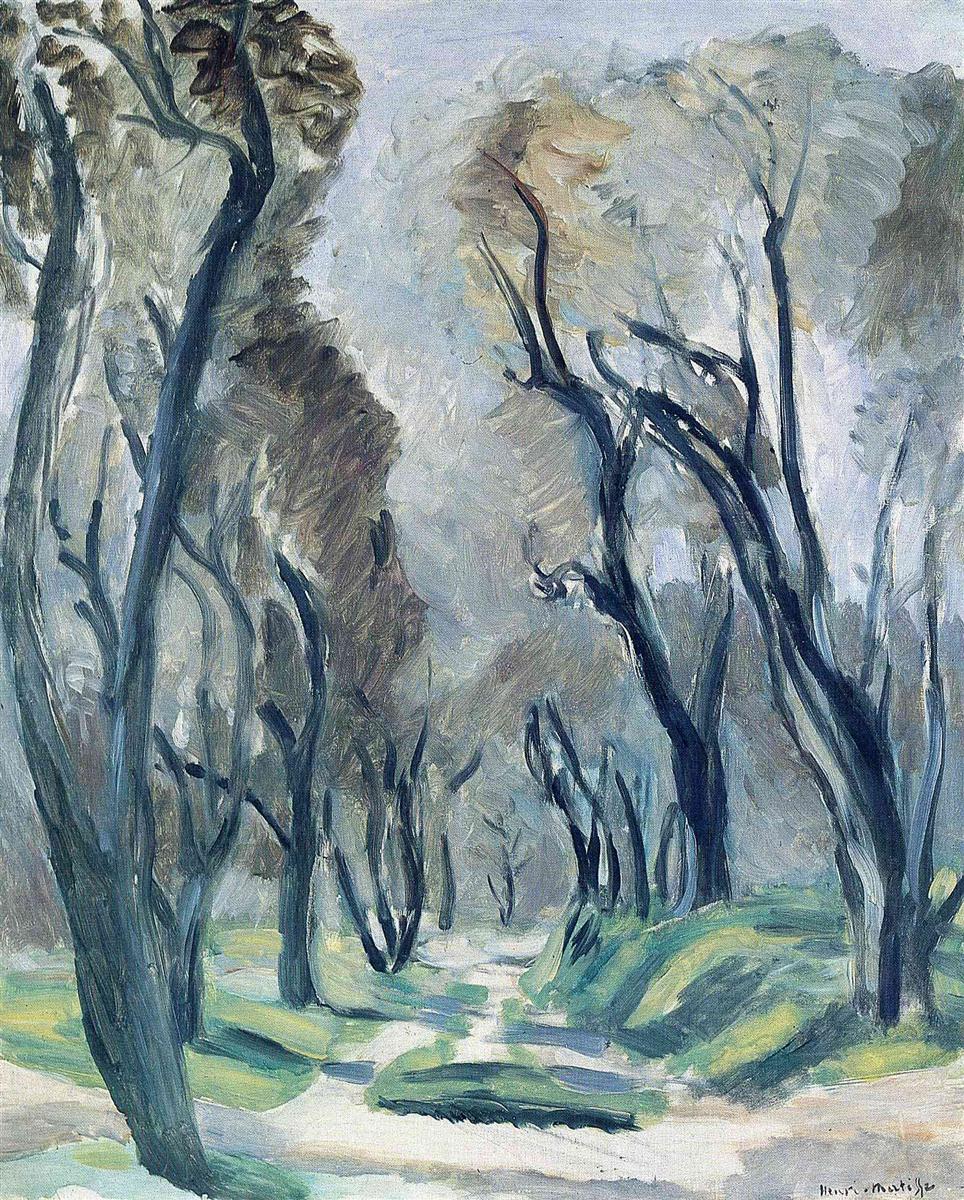

Henri Matisse’s “Avenue of Olive Trees” (1920) is a quiet storm of sensation. The composition is simple—an undulating path that slips through a grove while slender trunks lean and converse overhead—yet the canvas vibrates with movement. Matisse turns cool blues, blue-greens, and pearly grays into a living atmosphere; he writes the trees as calligraphic arcs; he lets the ground breathe in mint and celadon. What could have been a postcard motif becomes a condensed experience of walking, pausing, and inhaling under shifting light. The painting is not a description of a place so much as a tempo for seeing, a choreography in which line, color, and air keep time together.

Historical Moment And Matisse’s Return To Calm

In 1920 Matisse was shaping the gentler classicism that defines his postwar years. The blazing shocks of Fauvism had given way to clarity, economy, and a pursuit of serenity that never sacrificed vitality. On the Mediterranean coast, olive trees were part of daily life—gnarled, resilient, and endlessly various in silhouette. They offered the artist a subject at once humble and inexhaustible: a structure of trunks and canopy that could be bent into rhythms while admitting an infinity of tonal nuance. “Avenue of Olive Trees” belongs to this search for order after upheaval. The palette is cooled, the structure clarified, the brush confident, and the mood poised. It is a painting that finds modernity not in noise but in concentration.

Subject And Symbol Without Story

Olive trees carry thick cultural meaning—longevity, endurance, peace—yet Matisse refuses overt symbol. He lets the trees speak through posture. Each trunk inclines or twists with a personality formed by wind and weather; branches rise like arms in mid-gesture; the path interlaces with pale stones and islands of grass. Human figures are absent, but their trace is everywhere: the route is worn, the distances are scaled to stride, the clearings feel sized for breath. The result is an image of companionship between nature and passage, where continuity is affirmed without allegory.

Composition As A Vaulted Corridor

The composition is a masterclass in architectural rhythm. Tall trunks at left and right tilt inward to form a canopy, an organic nave whose ribs are branches. The path does not run straight; it splits and rejoins, cutting light shapes into the ground and then stitching them with shadow. Matisse places a quiet opening at the center where the grove thins and the sky whitens—a visual breathing point that prevents the corridor from closing in. The forward trees anchor the foreground with broad, dark gestures; successive ranks step back in lighter registers, so the eye proceeds at the pace of a stroll. Everything works toward the sensation of passage, not the diagram of perspective.

Color, Temperature, And A Cool Radiance

The painting’s weather is cool and rinsed. Blues run from inky at the trunk bases to milk-tinted in the sky; greens lean toward turquoise and sea-glass; grays soften into pearl. Warmth is rationed to a few olive-brown notes in the canopy and a whisper of ocher peeking from the earth. This temperature map is not merely naturalistic; it stabilizes mood. The cool sets the mind to clarity, like the lucid air after rain, while the small warm notes keep the picture from chilling. Chromatic restraint heightens sensitivity: a faint shift in blue reads as depth; a smudge of green becomes a breath of grass.

Brushwork And The Signature Of The Hand

Matisse’s brush is frank and rhythmic. Short, feathering strokes tessellate the foliage; longer, elastic sweeps inscribe the trunks; brisk, lateral passes lay the path. Paint density varies strategically. On the trunks it gathers, lending heft; in the sky and path it thins, allowing the canvas tone to flicker through like light. He avoids literal bark and pebbles, trusting the eye to supply such specifics. What he paints are relations: the pressure of shadow against ground, the flare where leaf-masses meet sky, the eddy where the trail bends. The surface tells the story of decisions—placed with speed, judged with calm.

Space And The Illusion Of Air

Depth arrives less by ruler-straight perspective than by atmosphere. As trees recede, their values lighten and their edges loosen; branches thin to calligraphy; the path narrows and cools. Matisse layers these cues until space becomes breathable rather than theatrical. The viewer occupies a zone of near ground—close enough to feel the trunks’ weight—while the middle distance opens at a humane pace, and the far space remains a promise of light. The grove is not a stage set; it is a volume of traversable air.

Rhythm, Movement, And The Musical Line

Looking at the picture is like listening to a melody played on a single instrument. The trunks script phrases: ascent, bend, flourish, pause. On the left a tall dark bar begins the measure; on the right, answering arcs respond; a counter-rhythm lifts from sapling silhouettes in the center. Meanwhile the path keeps time, repeating pale beats that syncopate with the verticals. This musicality is not a metaphor tacked on after the fact; it is the painting’s inner engine. Matisse composes the grove as a score for the eye, a sequence of notes that yields harmony rather than description.

Light That Builds Structure

Light is the canvas’s quiet architect. Pale zones in the path and sky form a cruciform stabilization—the vertical pull into distance and the lateral spread under the canopy—that holds the composition in balance. Shadows do constructive work: they carve the trail’s turns, seat the trees in the ground, and knit greens into blues. Nowhere does light become glare. Instead it is brushed onto forms like a veil, unifying without flattening. You don’t merely see light on things; you feel light as the medium that binds things together.

The Poetics Of Restraint

This is a painting of what Matisse leaves out as much as what he puts in. Absent are dazzling sunbursts, chattering detail, and aggressive color contrasts. What remains is essential: line, value, interval, temperature. Restraint is not a retreat from intensity; it is the condition for a deeper one. The eye, released from managing spectacle, attends to nuance—the slight warm accent inside a cool canopy, the delicate overlap where two branches cross, the faint brightening that marks the path’s destination. The painting’s quiet is earned and therefore durable.

Dialogues With Place And Tradition

Olive groves have tempted painters from Corot to Cézanne, and Matisse absorbs the tradition while bending it to his grammar. The vaulted composition nods to classical ways of framing sacred spaces, yet here sanctity is sensory: the sacredness of shade, breath, and walking. The trees are not weighty sculptural masses; they are drawn forms, more arabesque than modeling, recalling Matisse’s lifelong love of the sinuous line. And though the motif is Mediterranean, the palette avoids postcard warmth for a tempered cool that feels modern in its sobriety.

A Landscape Of Recovery

Painted at the beginning of a decade defined by rebuilding, “Avenue of Olive Trees” can be read as an image of quiet resilience. The trees have leaned and endured; the path remains open. There is no grand narrative, only continuity. Without symbolism, the painting affirms a simple, restorative truth: steadiness returns in measured steps. The grove offers a place where sensory order can be rediscovered—balance of vertical and horizontal, of warm and cool, of weight and air.

Technique, Layers, And The Logic Of Simplification

Under the visible strokes lies a scaffold of broad tonal blocks. Matisse likely established horizon and major masses with thin paint, then developed trees and ground by layering slightly denser passages, allowing overlaps to create soft edges that read as movement. The method obeys a consistent logic: simplify forms to their functions in the composition—this trunk anchors, that branch points, this path beat carries the eye forward—and then tune values to keep the whole breathing. The virtuosity is not in bravura flourish but in sustained, exact simplification.

What Careful Looking Reveals

Sustained attention brings small discoveries. The leftmost trunk, which at first reads as a single dark mass, turns out to be a weave of blue-greens and blue-blacks gently inclining toward the path, initiating inward motion. Near the center, two branch tips cross to form a subtle X, a hinge around which the canopy turns. In the foreground, a low mound of grass breaks a run of pale earth, its cool green lifting like a chord change. Toward the distance, the path’s pale beats compress, producing the sensation of time tightening as one nears the bright opening. None of these are tricks; they are the knitwork that holds the viewing experience together.

Kinships And Differences With Related Works

Compared with Matisse’s interiors from the same year—women in striped chairs, tables draped with patterned cloths—the olive avenue is stripped of ornament but adheres to the same grammar. The chair’s enclosing curve becomes the canopy’s arc; the carpet’s repeating motifs become the path’s beats; the calm, moderating palette remains. Set beside more high-chroma Fauvist landscapes, this painting keeps the commitment to flat shapes and strong contours while trading shock for resonance. It is a sibling to his other olive-grove scenes of the period: each offers a variation on how much color can be cooled and how much line can sing without breaking the spell.

The Experience Of Walking

Perhaps the painting’s deepest success is that it translates the act of walking into pictorial terms. The path narrows and widens like breath. Trunks lean as the body does when negotiating uneven ground. Brushstrokes accelerate in foliage and slow over open patches, echoing the changing sensation of pace. Even the color behaves like weather felt during a stroll—cool light, brief warm eddies. Looking becomes kinesthetic. You do not only observe the grove; you move through it.

Human Presence Without A Figure

No one appears, yet the image feels inhabited. The scale of trunks to path, the clarity of the route, the small plateaus of grass that look like places to pause—all suggest design in dialogue with passage. The painting thus finds a human dimension without inserting a person. It offers viewers the dignity of occupying the space themselves. The invitation is subtle but insistent: follow the pale notes, stand in the open light, and let the air of the grove settle your gaze.

Light As Memory, Not Meteorology

Although the picture registers a particular kind of day—cool, slightly overcast—the light also functions as a memory device. It is the kind of illumination that makes edges gentle and colors thoughtful, the light under which recollection clarifies. The avenue becomes a remembered place as much as a seen one, and the painting reads like a distilled recollection of many walks rather than a single encounter. This is part of its power: it speaks to our own memory of paths, not just to Matisse’s.

The Painting’s Lasting Promise

What remains after looking is a mood: steadiness, lucid freshness, the sense that clarity is possible without hardness. The grove exemplifies Matisse’s conviction that art can be a refuge without becoming escapist. The balance he constructs—between motion and rest, cool and warm, detail and field—feels ethical as well as aesthetic. It models an attention that is careful, calm, and alive, the kind of looking that the world rarely demands but that the best paintings quietly teach.

Conclusion

“Avenue of Olive Trees” transforms a modest motif into a sustained meditation on rhythm, air, and measured joy. With a few colors and a fluent line, Matisse composes a corridor of breathing light in which the eye walks, rests, and walks again. The grove shelters, the path invites, and the painting’s orderly music lingers long after the canvas is out of sight. It is a picture that doesn’t raise its voice, yet it speaks with authority about how beauty can be made from restraint and how clarity can be felt as tenderness. Under its cool canopy the ordinary act of moving forward becomes quietly ceremonial, and that ceremony is what makes the image endure.