Image source: wikiart.org

A Portrait Forged from Night and Line

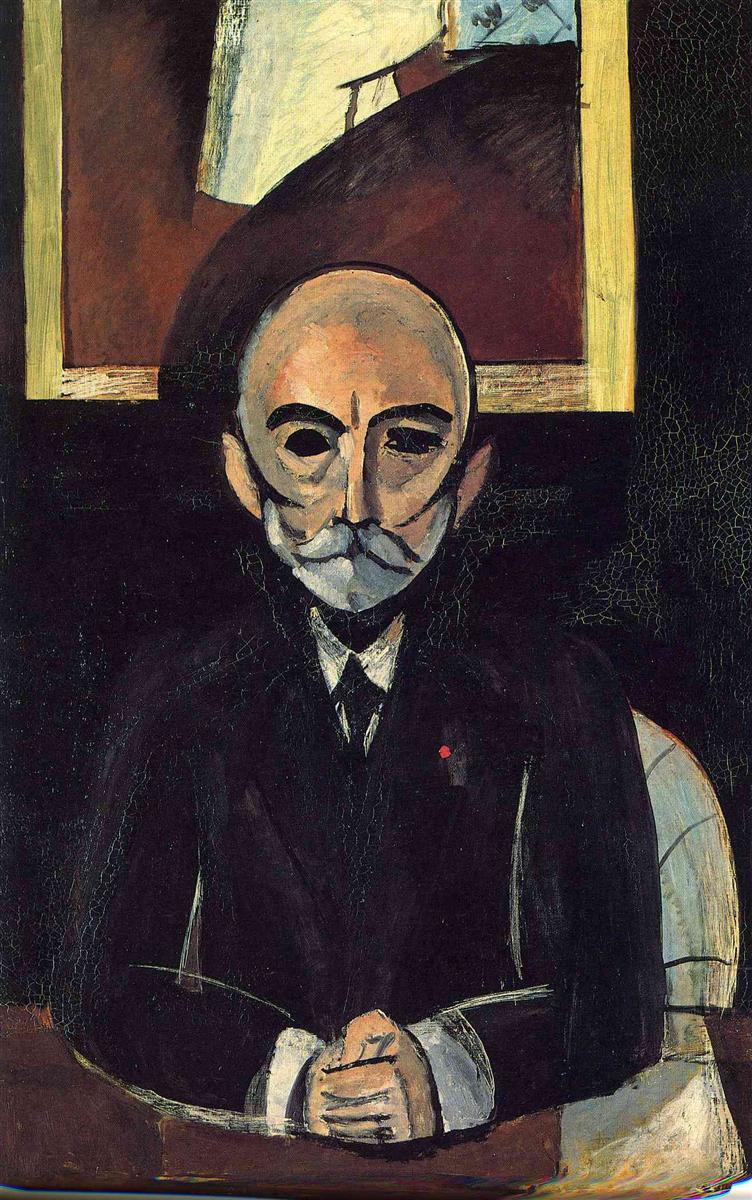

Henri Matisse’s “Auguste Pellerin (II)” (1917) confronts us with a figure carved out of near-black. The industrialist and collector sits rigidly at a desk, hands clenched before him, a small red pin burning on his lapel like a pilot light. Around him the room is reduced to emphatic planes: a dark wall, a framed picture that tilts a wedge of rusty red into the upper register, and a sliver of chair back that echoes the sitter’s curved shoulders. Where many portraits tell stories with props, this one builds presence from a few immovable relations—mass against void, edge against plane, flesh against suit—so that character arrives through structure.

The Chosen View and Its Architecture

The vantage point is frontal and close, placing the viewer at the same desk where Pellerin sets his clasped hands. Matisse organizes the composition as three stacked registers: desk in the lowest band, torso and head in the middle, framed picture in the top. The geometry is tight. The bald dome of the skull is circled by a wide, dark halo of background; the triangular wedge of the beard plants a visual plumb line; the long arc of the shoulders swells into the black mass of the suit. Everything leans gently inward toward the axis of the face and hands, a design that tightens the encounter and concentrates the sitter’s presence like a lens.

Color as a Measure of Authority

The palette is disciplined almost to austerity. Black dominates, modulated into blues, browns, and bottle-green within the suit and background. Skin arrives as a limited sequence of ochres and cool grays. The tiny red of a decoration on the lapel is the portrait’s single bright chromatic accent. By withholding color elsewhere, Matisse forces that red to carry disproportionate weight: it punctuates the field, signals rank, and keeps the surrounding blacks from sinking into monotony. The framed picture overhead injects pockets of rust, cream, and cool blue that animate the upper zone without disturbing the sitter’s austere silhouette. Color in this portrait is not costume; it is governance.

Black as a Constructive Color

Black is not a void here; it is architecture. Matisse uses it to define the suit as a single, load-bearing mass, to trim the edges of lapel, collar, and cuff, and to map the features of the face with an economy that reads like calligraphy. The brows are two emphatic arches, the nose bridge a vertical stroke flanked by cool planes, the moustache a pair of careful curves that complete the mask. These marks thicken and thin according to pressure so that line becomes a language of decisions rather than an outline to be filled. Because black performs as a color among colors—not just the absence of light—it can carry volume, weight, and interval all at once.

A Face Constructed from Planes

Look closely and the head resolves into a set of precise, interlocking planes. The forehead is a broad, matte dome punctuated by a vertical groove. The eyes sit under powerful brows, their sockets stated with two shadowy triangles that do as much for likeness as any fine detail could. The cheeks are carved with cool grays that tuck toward the beard; the nose is a narrow, cool wedge, its edges tightened by adjacent shadows. The beard and moustache are triangles of light that sharpen the lower face like facets on a stone. Matisse anchors individuality not in descriptive trivia but in the fit of these planes, whose relations make the face inevitable.

Hands as Hinge and Oath

The clasped hands at the picture’s bottom edge are more than anatomical punctuation. They convert the studio exchange into a contract. Their placement at the desk’s front lip draws our space up against the sitter’s; their strong modeling—knuckles as small blocks of light, cuff as a pale band—grounds the portrait’s abstraction in tactile fact. If the head carries the authority of thought, the hands state purpose. They also complete the triangular choreography of beard, lapel V, and wrists that stabilizes the whole design.

The Framed Picture: A Window of Counterpoint

The image within the image matters. In a field otherwise ruled by black and cool flesh, the upper picture injects a slanted plane of rusty red, a creamy wedge, and a slice of blue. Whether it echoes an actual painting in Pellerin’s collection or serves as studio invention, it does several things at once. It raises the temperature at the top of the composition so the portrait does not deaden under its own gravitas. It mimics the desk’s oblique edge, creating a diagonal dialogue across the vertical axis. It also casts the sitter as a man who lives among pictures, placing art literally over his head like a mantle of thought.

Texture, Craquelure, and the Truth of the Surface

Unlike the smoother finish of many society portraits, “Auguste Pellerin (II)” leaves its surface candid. The blacks are brushed in varied directions, recording the arm’s swing. In places micro-craquelure creeps through the darks, a fine network that reads like the painting’s own history written into the varnish. Matisse lets these material facts live, refusing to polish the image into anonymity. The surface becomes a form of honesty: this is paint behaving as paint, and the authority it delivers is inseparable from the hand that set it down.

Light as Clarifier Rather Than Drama

The lighting is broad and untheatrical. Highlights collect along the collar’s edge, at the tips of the moustache, on the knuckles and the crown of the skull. Shadows quiet the eye sockets and undercut the beard, but they never split the head into harsh halves. By keeping light as an even envelope, Matisse safeguards the primacy of shape and line. Illumination in this portrait reveals decisions rather than staging a scene.

From “Auguste Pellerin (I)” to “(II)”: A Step into Severity

When compared with Matisse’s other portrait of Pellerin from the same year, the evolution is instructive. In the earlier version the room glows in warm ochres; books and a green chair soften the ambiance; the hands rest in a more social poise. Here warmth recedes and the palette darkens; the background swallows ornament; the head hardens toward an emblem. The two portraits are not contradictions but complementary truths: one seats influence in a comfortable, lived interior; the other abstracts authority into a near-icon. Together they show Matisse testing how far simplification can go before likeness and presence disappear. In “(II)” he finds a stringent answer.

Psychology Without Performance

The temptation in portraiture is to pull emotion from theatrical cues: a smile, a frown, a thrown glance. Matisse sidesteps that route. Pellerin’s eyes meet us levelly; the mouth is closed; the posture is upright and immobile. Psychology arrives from structure instead. The severe central axis, the clenched hands, the weight of black mass around a pale face—all of these add up to a temperament of control. The tiny, glowing badge on the lapel reads not as decoration but as a point of heat within a disciplined climate. Everything signals authority that does not need to prove itself.

1917: Wartime Discipline and the Return of Black

The date situates the painting in Matisse’s wartime shift from Fauvist blaze to measured construction. Black returns as a principal actor; chroma is rationed; planes and intervals carry drama. This discipline is not chilly. Instead, it makes the few colors and edges that remain feel powered by necessity. “Auguste Pellerin (II)” embodies this ethic. It is pared to the bone without ever losing pulse, a portrait whose gravity comes from economy rather than heaviness.

Drawing with Economy: The Mask and the Man

Some viewers have noted the mask-like quality of the face—the simplified sockets, the strong nose bridge, the moustache as twin commas. Rather than signaling detachment, this mask logic clarifies essentials. It borrows the directness of non-Western carving and early modernist sculpture, yet it remains anchored in natural observation by the careful temperatures of the skin and the exactness of the planar joins. The man and the mask are not opposites; they are the two halves of Matisse’s method: reduce to structure, then breathe life into that structure with subtle color.

The Desk as Stage and Boundary

The desk is a shallow trapezoid of warm brown that lifts toward the viewer. It does the vital work of staging the hands and preventing the black suit from dissolving into the black background. At its near edge, a faint, cool line catches light where varnish or the wood’s finish turns plane to edge. That small optical event ties the painting to the world of usable objects and gives us a tactile foothold. The portrait’s severity never drifts into abstraction because the desk keeps summoning the present tense of work.

The Eye’s Path Through the Picture

The itinerary of looking is deliberately concise. Most viewers enter at the illuminated skull, drop to the gloved eye sockets, descend the nose’s narrow ridge to the moustache and beard, then fall to the clasped hands before returning up the lapels to the red badge and out to the framed picture above. Each bend of this circuit is marked by a major contrast—light on dark at the skull, dark on light at the eyes, cool on warm at the desk—so the loop can repeat without fatigue. The portrait occupies the gaze not with variety but with cadence.

What the Portrait Refuses

Equally telling is what Matisse declines to show. There is no narrative of profession, no table full of instruments, no window onto city or sea. He refuses the rhetoric of anecdote and instead allows structure to speak character. Even the suit—so often an emblem of class in portraiture—is nearly abstracted into a single field, its buttons and seams noted only where they aid the design. This refusal is not deprivation but concentration. Strip away the dispensable and the necessary grows eloquent.

Material Presence and the Feeling of Time

The painting’s darks hold not only pigment but time. In their depths you can read the slow drying of oil, the settling of varnish, the faint craquelure that maps the years since 1917. That physical history becomes part of the portrait’s meaning. The image of authority has endured not as a brittle icon but as a surface that admits its own aging. Matisse’s craft doesn’t hide that truth; it frames it.

Why “Auguste Pellerin (II)” Endures

This portrait lasts because it gets difficult things right with very little. It locates character not in expression but in design, not in props but in planes, not in anecdote but in relation. It shows color doing structural work, black made eloquent, line carrying psychology. From across a room it reads instantly as a dark, frontal presence broken by a sliver of light at collar and hand and by a single spark of red. Up close it yields the pleasures of brush and edge, of tiny temperature shifts in skin and the deliberate pressure of contour. It is both a likeness and a proof that painting can build authority with an almost musical economy.

A Closing Reflection on Power and Paint

Matisse sits the patron across from us and lets paint do the talking. There is no flattery, only clarity. Black organizes, red punctuates, planes interlock, and a human presence materializes at desk’s edge. The portrait’s lesson is large and simple: when structure is right, very little else is needed. “Auguste Pellerin (II)” stands as a compact demonstration of that principle, a sober image whose quiet power grows each time the eye returns.