Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

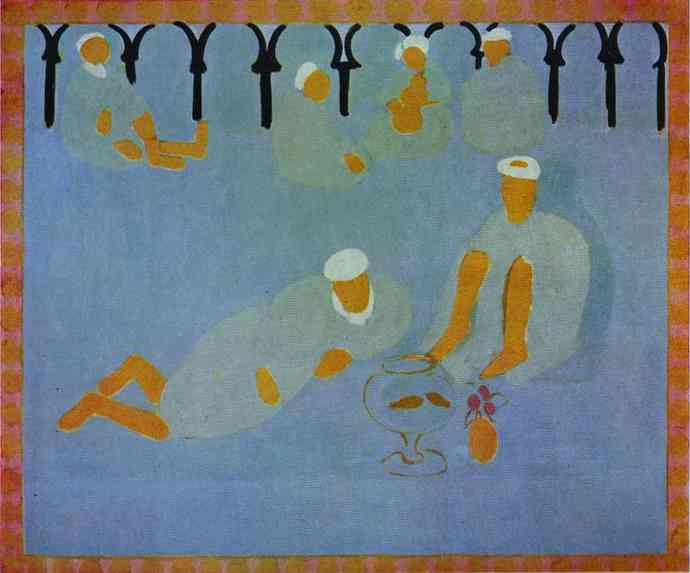

Henri Matisse’s “Arabian Coffee House” (1913) translates a quiet social scene into an architecture of color, rhythm, and stylized form. On a cool blue-lavender ground, simplified figures in pale garments gather along the top register and at the right foreground; a black arcade of horseshoe arches floats above them; and an ornamental border in pink-orange frames the whole. In the lower right a small still-life—an urn-like vessel with a few orange shapes and a single flower in a tiny pot—anchors the composition. The painting is less a documentary glimpse of a café than a meditation on repose, hospitality, and the decorative unity that Matisse pursued after his Moroccan journeys. It compresses the heat and silence of a shaded interior into pared-down signs, inviting viewers to experience the scene as a calm, breathing surface rather than a piece of narrative illustration.

Historical Context

Matisse visited North Africa in 1912 and again in early 1913. The clarity of Moroccan light and the ornamental logic of courtyards, textiles, and arches confirmed his long quest for simplification. From the early blaze of Fauvism he had learned that color could build form; Morocco taught him that light could be rendered by large, unmodeled planes and that architecture itself could be seen as pattern. “Arabian Coffee House” belongs to this second period in Tangier, when he reduced figures and spaces to emblematic shapes and treated the picture surface like a woven field. Instead of the analytic fragmentation of Cubism, Matisse chose a different modernism: coherence through color intervals, serenity through rhythmic repetition, and feeling through the least number of marks.

Subject and Iconography

The painting evokes a coffeehouse or shaded terrace where men rest and converse. No faces are individualized; figures are ovals and lozenges with small orange notes for hands, feet, and faces. Some sit upright, one reclines on an elbow, another cradles a vessel. Their white caps and soft garments identify them as members of a shared social world rather than characters in a story. In the foreground at right, a kneeling figure leans toward a glass vessel—its outline drawn with a few spare curves—beside which sits a tiny orange pot with a pink blossom. This pair, vessel and flower, echoes Matisse’s continuous interest in still-life as a counterpoint to the human body. The coffeehouse appears as a place of deliberate slowness, with objects and people occupying the same calm register.

The Decorative Frame and the Arcade

Matisse surrounds the scene with a painted border of pink and orange, a soft check or scallop that behaves like a textile edge. It declares the work’s decorative ambition and prevents the image from spilling into illusionistic depth. Inside that border, the upper edge carries a frieze of black, keyhole-shaped arches reminiscent of Moorish architecture. The arcade functions as a visual bar, a steady beat repeating across the top while also hinting at a shaded colonnade. By reducing the arches to silhouettes, Matisse detaches them from strict architecture and makes them work as pattern—ornament that both defines and harmonizes the gathering below.

Color Architecture

The painting is anchored in two temperature families: a cool field of blue-lavender for the floor/space and warm oranges and pinks for skin, accessories, and the framing border. The figures’ garments are pale gray-green pools that lighten the blue beneath them; their faces, hands, and feet are rendered in compact orange shapes that glow against the cool ground. The border’s pink-orange repeats that warmth at the periphery, keeping the painting’s heat contained. Black appears only in the arcade above, a measured accent that grounds the composition without heavy shadow. This restrained palette—cool expanse punctuated by warm notes—produces a state of equilibrium that mirrors the subject’s quiet sociability.

Space as Shallow Stage

Conventional perspective is absent. The coffeehouse is a shallow field where people and objects float at similar scale regardless of their supposed distance. Overlap is minimal; instead, Matisse builds space by vertical placement and tonal contrast. Figures higher on the canvas suggest a rear zone; the two larger forms at the right foreground mark nearness; yet all parts remain on or near the surface. The result is not a mistake of perspective but a choice that allows the painting to read as a textile-like plane. The viewer is not asked to walk into a room so much as to occupy the calm rhythm of a patterned surface.

Line, Edge, and Shape

Drawing is accomplished with the fewest strokes. The arcade is a sequence of single, confident silhouettes. The vessel and its stand are sketched with a handful of curving lines that never fully close, inviting the eye to complete them. Figures are constructed from soft ovals and bean-shaped masses, their edges sometimes feathered so the ground’s color participates in their contour. Where Matisse needs emphasis—a hand, a foot, a cap—he sets an orange shape with crisp edges. This economy of line gives the painting an air of inevitability, as if the forms had always belonged to the field.

Rhythm and Repetition

Repetition structures the image. The black arches beat across the upper register like musical counts. The figures’ caps—small white disks—blink in a counter-rhythm. Orange hands and feet punctuate the field at regular intervals, guiding the eye from one body to the next. Even within the pale garments, Matisse repeats lozenge-shaped patches of color to prevent the forms from reading as empty silhouettes. These rhythms produce a steady, communal pulse appropriate to a scene of rest and conversation.

The Role of Negative Space

The painting’s most abundant element is what is not drawn: the blue-lavender ground. This negative space does not merely isolate figures; it becomes the air of the coffeehouse, the coolness of shade, and the mental quiet of pause. By allowing so much unbroken field, Matisse amplifies the significance of each warm accent. A single orange foot or a small pink flower can carry surprising weight because the surrounding space listens. This discipline of restraint is a hallmark of his Moroccan pictures: meaning is achieved by intervals rather than abundance.

The Still-Life Motif

At the right foreground, the vessel and flower create a modest still-life within the figure group. The vessel might contain coffee or simply serve as a decorative urn; either way, it introduces transparency and curvature to a composition otherwise built from opaque ovals. The little flower repeats the border’s warm palette and humanizes the scene: hospitality takes the form of a small offering. Matisse often set living, carved, and painted things side by side to show how art mediates life. Here the vessel stands between people, acting as focal point and shared purpose, but it remains a sign—spare, open, barely inscribed—so the painting’s calm is undisturbed.

Light and Atmosphere

The image evokes the cool shade of an interior or courtyard filtered through a gentle, even light. There are no cast shadows. Illumination is communicated by the relative clarity of warm accents and the softness of the garments’ tones against the ground. The arcade’s black reads as deep shade—perhaps the underside of a roof—while the border functions like a sunlit fringe. The atmosphere is, again, a color decision: lavender-blue as air, orange as warmth. This chromatic approach to light reflects the lessons Matisse drew from North Africa, where midday sun simplifies and saturates rather than models.

Ethics of Looking

Scenes from foreign cultures have long tempted European painters toward picturesque display. Matisse’s strategy is restraint and respect. He does not individualize faces or stage narrative; he grants the figures shared dignity through posture and place. The quiet elimination of detail removes the voyeuristic, leaving a universal situation: people at rest, objects nearby, architecture providing shelter. Even the title’s generality—“Arabian Coffee House”—keeps the image open rather than pinning it to a specific locale. The painting’s ethic matches its form: clarity without intrusion.

Dialogue with Islamic Ornament

The work engages Islamic visual culture not by copying motifs but by adopting principles: an emphasis on surface unity, rhythmic repeat, and the harmony of geometric and vegetal forms. The arcade echoes the horseshoe arch without literal description. The border resembles a textile, but it is painted with broad, breathing strokes rather than precise pattern. Matisse found in these traditions a confirmation of his own belief that painting could be decorative and profound at once—decorative in its unity, profound in its capacity to create a durable mood.

Comparisons within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Arabian Coffee House” converses with the goldfish interiors and Moroccan portraits of 1912–1913. The cool field set against warm accents reappears in “Zorah on the Terrace,” where a triangular shaft of light cuts blue walls and a goldfish bowl glows at the side. The ornamental border and cropped arcade anticipate later Nice-period works in which screens, shutters, and patterned cloths frame figures at leisure. Compared to the energetic studio canvases featuring dancers or bold still-lifes, this coffeehouse is more meditative—a communal counterpart to those private interiors.

Process and Surface

The paint handling suggests thin, even layers laid over a toned ground, with small reserves left for accents. In several figures the ground flickers through at the edges, creating a halo that sharpens the silhouette without hardening it. The border’s warm strokes vary in saturation, evidence of quick adjustments as Matisse tuned the frame to the blues within. The arcade’s black is laid in with a loaded brush, confident and unbroken. Such surface variety keeps the otherwise quiet image alive under close viewing.

Psychological Tone

The painting’s mood is neither festive nor solemn; it is restorative. The figures’ poses—reclining, seated, gently attentive—communicate a shared permission to slow down. The warm notes of hands and faces do not shout; they glow. The absence of sharp contrast or narrative event invites contemplation: viewers feel themselves entering a cooler mental temperature, one that matches the blue field. This poised serenity is central to Matisse’s stated aim of offering an art of balance and repose, not escapism but a disciplined harmony.

Why the Work Matters

“Arabian Coffee House” matters because it demonstrates how radically pared forms can still convey place, culture, and social feeling. It shows Matisse uniting figure, still life, and architecture within a single decorative field while avoiding stereotype and anecdote. The painting advances the argument that modern painting can be constructed like a textile—flat, rhythmic, ornamental—without losing human presence. In a moment when many avant-garde artists pressed toward fragmentation, Matisse built unity; where others amplified tension, he refined calm. This canvas is a lucid instance of that choice.

Conclusion

With a handful of colors and a grammar of ovals, arches, and a soft border, “Arabian Coffee House” creates a world of shade and quiet talk. People recline, a vessel waits, a small flower brightens the ground, and a rhythm of arches watches at the top like a measured breath. The image does not demand attention through spectacle; it earns it through balance. Standing before it, one senses the lesson Matisse carried from Morocco into the rest of his career: that clarity is generous, and that a painting can make stillness vivid by arranging color so well that it seems to think.