Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

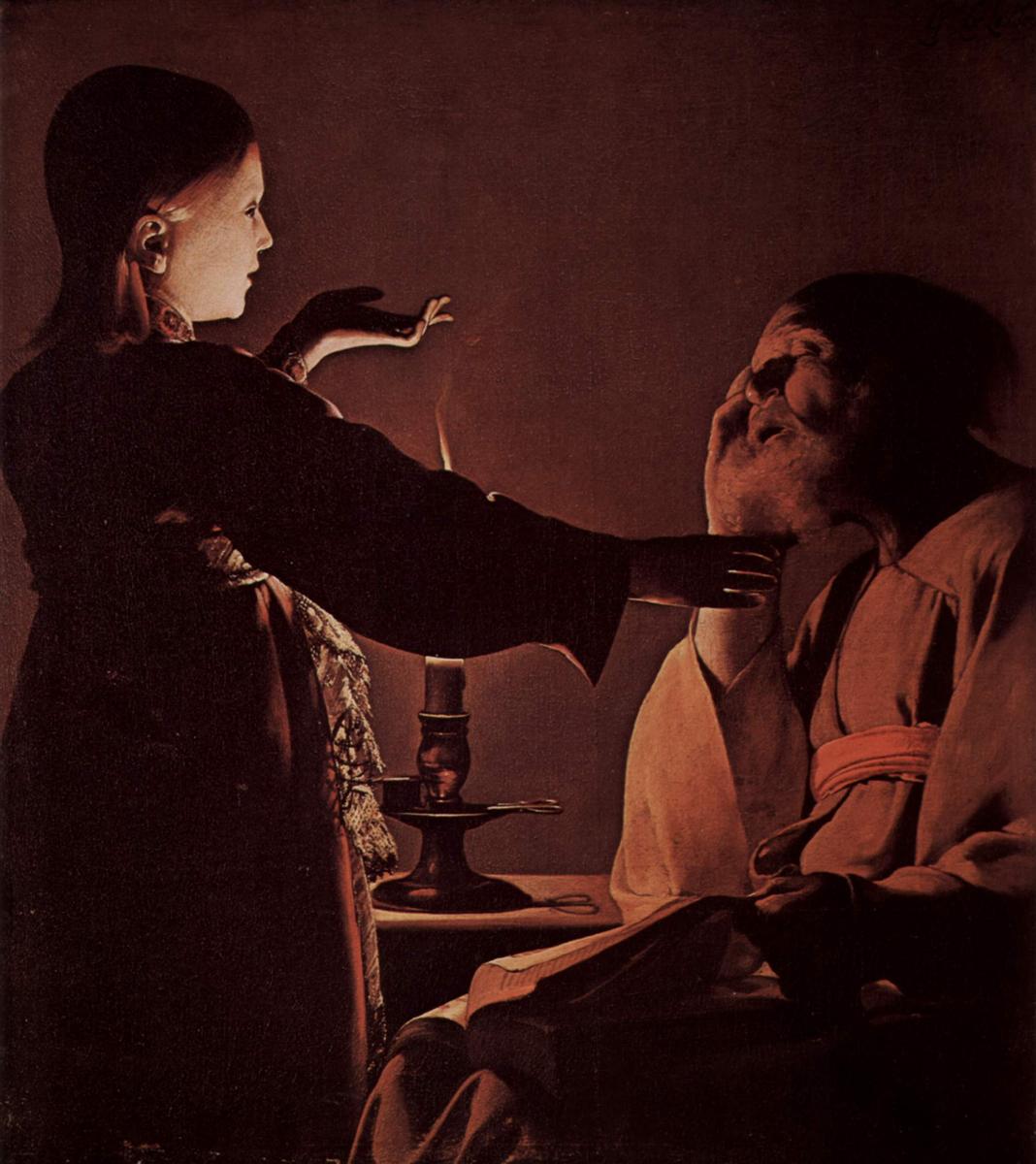

Georges de la Tour’s “Appearance of Angel to St. Joseph, also called The Song of St. Joseph” (1640) is one of the most intimate annunciations in Baroque art. Instead of blazing heavens or trumpeting cherubim, de la Tour stages a nocturne in a modest room: a young angel approaches the sleeping or half-waking Joseph; a single candle mediates the encounter; a book rests open as if the craftsman had drifted from reading into reverie. The angel’s hands hover like quiet instruments of music, the left cupped upward, the right poised near Joseph’s mouth, while Joseph’s own hand props his cheek in a gesture of drowsy wonder. The painting’s power lies in its refusal of spectacle. Light, gesture, and silence do the announcing, and their eloquence is inexhaustible.

Composition and the Architecture of a Whisper

The painting is built on a crosswise dialogue between two bodies. The angel stands at the left in profile, a vertical column of youth, while Joseph occupies the right in a sloping diagonal of age and fatigue. Between them, the candle marks a small, luminous axis. De la Tour reserves the largest field of empty space for the wall behind and above the candle; that void functions as a sounding board for the encounter, a chamber where a whisper can be heard. The angel’s extended arms describe a gentle arc that funnels our gaze toward Joseph’s face; his bent head tilts back toward the child, completing a compositional loop. No object distracts. Even the open book is a quiet plane in the lower right, a reminder of thought rather than a competing protagonist. The architecture is the architecture of a lullaby.

Light as Messenger and Meaning

De la Tour’s nocturnes always trust one light. Here the candle is a small, steadfast flame set in a dark brass holder. Its glow lands first on the angel’s face, then climbs the sleeves and lips of the child, then reaches Joseph’s cheek and collarbone, and only after that warms the book and the edge of the table. The sequence is a doctrine: the messenger is made visible so that the message may be heard; the hearer is then drawn into that same light; the words that have been pondered before sleep become newly legible by the visitation. The candle’s flame also reads as a slender bridge between divine initiative and human receptivity. It is not a theatrical blaze; it is the exact amount of light needed for trust.

Chiaroscuro Without Alarm

While the canvas belongs to the Caravaggesque tradition, its chiaroscuro is gentle, almost pastoral. The angel’s profile is modeled by long, even tonal transitions; the shadows along the robe dissolve into a red-brown dusk rather than a black maw. Joseph’s form emerges as a sequence of simple planes—the sphere of the head, the cylinder of the forearm, the wedge of the collar—turning smoothly from light into rest. De la Tour never lets darkness threaten the scene’s peace. Instead, shadow functions as a blanket that protects focus, a soft perimeter that keeps the miracle indoors.

Gesture as Conversation

No words are painted, yet everything speaks. The angel’s right hand approaches Joseph’s beard the way a musician brings a bow toward a string—not touching yet, already sounding. The left hand turns upward as if offering the sentence that Joseph must receive, its palm a small stage where meaning can rest. Joseph’s hand, meanwhile, props his cheek and partly covers his mouth, a natural posture of a man startled awake, but also an eloquent sign of awe: speech interrupted by something larger than reply. The hands, four of them, carry the painting’s grammar—invitation, offering, assent, and silence.

The Psychology of Sleep and Call

De la Tour excels at painting interior states without melodrama. Joseph is not terrified; he is called. His eyelids lift into the light; his head angles toward the voice; his lips part beneath the shelter of his hand. We feel the weight of the day in his posture, yet we also see the body rearranging itself to receive purpose. The angel, with the calm of a nurse waking a patient, keeps his movements small. The psychology is credible because the painter refuses extraordinary bodies. They are not marble; they are people who breathe.

The Candle as Theological Device

The candle is more than illumination; it is theology made domestic. Its flame is slender and upright, neither guttering nor triumphant. The wick is trimmed; the oil or tallow is enough. If the angel is a messenger and Joseph a hearer, the candle is the medium; it makes the text legible, the face readable, the touch gentle. In Christian imagination, Joseph receives divine direction in dreams. De la Tour translates that mystery into a light we can see: a flame that, like the word of God, does not shout but persists. It makes a circle within which vocation becomes clear.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The painting’s palette is a chord of warm browns, velvety reds, and honeyed flesh, tuned by the off-white of Joseph’s robe and the lemony core of the flame. The angel’s garment, deep and dark, absorbs light so that the face can shine; Joseph’s robe gives back light in broad planes, emphasizing vulnerability. Because chroma is restrained, temperature does the emotional work. The room glows without glare, a human warmth that fits the tenderness of the event. Nothing brassy, nothing icy; a song in earth tones.

Texture and the Truth of Materials

Part of the painting’s persuasion lies in how materials behave. The brass saucer near the candle rims catches a firm highlight and then sinks into brown; the angel’s sleeve has a fine, almost chalky nap that receives light softly; Joseph’s robe reads as a heavier cloth with slower, deeper reflections. The book at lower right shows paper that lifts slightly along its inner gutter. These textures are modest, but they make the world trustworthy. When everything tactile is believable, we accept the invisible content of the scene with fewer defenses.

Space, Silence, and the Chamber of Night

De la Tour’s restraint with architecture is deliberate. A table edge. A book. A candle. A wall. The rest is air and hush. That hush is not emptiness; it is the active soundproofing of contemplation. In such a room, an angel does not need wings or thunder. The painter’s economy gives sound to quiet gestures: the slide of robe, the intake of breath, the soft rasp of a page turned before sleep. The silence is the annunciation’s partner.

Iconography Made Practical

The painting’s symbols do not float; they work. The open book is Joseph’s contemplation of Scripture or a manual of prayers—meaning already in process before the visitation. The candle is both light and hourglass; it measures the time of the message. The angel’s youthful face embodies the paradox of divine instruction carried by smallness. The sash around Joseph’s waist marks common dress, not priestly office; the visitation meets him in his craft, in his home, in fatigue. De la Tour keeps every sign connected to use so meaning never hardens into emblem.

The Angel as Child, The Message as Song

The alternate title, “The Song of St. Joseph,” is not an idle poet’s flourish; it comes from the painting’s music of hands and light. The angel’s gestures resemble conducting—one hand setting tempo, the other shaping phrase. The proximity to Joseph’s mouth hints at voice: what he will say, or the prayer that leaves him unspoken. By choosing a youthful messenger rather than a monumental archangel, de la Tour tunes the scene to lullaby pitch. The message is not shouted; it is sung into the softest space of a household night.

Relation to De la Tour’s Domestic Nocturnes

This canvas belongs with the artist’s other single-light meditations: the Magdalenes, the reading Jeromes, “Education of the Virgin,” “The Newborn.” Each trusts the candle as ethical instrument. In those works light keeps watch over study, repentance, or maternal care; here it guards communication. The painter’s late style moves toward abstraction through simplification—large planes, few objects, quiet silhouettes. “Appearance of Angel to St. Joseph” is among the purest examples: half the picture is breathable darkness; the other half is a duet of faces and hands. The simplification amplifies tenderness.

The Ethics of Looking and the Viewer’s Position

We stand just outside the circle of the candle, close enough to feel warmth, far enough not to startle the sleeper. No one seeks our gaze. The painting instructs our eyes by example: be steady, do not intrude, let light be fair. If we match the angel’s patience, the image yields more; if we demand spectacle, it gives us nothing. De la Tour designs an ethic of spectatorship that is also an ethic of care.

Time’s Breath and the Rhythm of Vocation

Time is present but unhurried. The candle is mid-burn. The book is mid-read. Joseph is mid-sleep. The angel’s hands are mid-phrase. Everything is caught in a living middle, the instant when a life tilts toward its next necessity. Joseph’s later actions—taking Mary as wife, protecting the child, rising at night to flee—are, in this painting, latent in a breath. De la Tour honors that breath by refusing to depict what comes after. Vocation begins here, in the quiet reddened by a small flame.

Humanism Without Sentimentality

The scene feels modern because the artist insists on common humanity. Joseph is old and tired; the angel is young and gentle; the message respects both conditions. There is tenderness but no sugar, belief but no propaganda. The miracle joins the grain of ordinary life rather than canceling it. In that decision lies the painting’s dignity: divinity takes the scale of a room, and instruction takes the form of a child’s hand near a worker’s cheek.

Technique, Edge, and Plane as Persuasion

De la Tour’s technique hides in the authority of shapes. He tightens the edge of the angel’s profile against the lit wall so the face reads instantly; he lets the far sleeve dissolve into shadow to keep attention on the hands; he carves the wedge of Joseph’s cheek with one lucid highlight and a long half-tone that slips back into beard; he chisels the rim of the candle’s saucer with a single acute stroke so the flame has a base as convincing as its light. Glazes warm the flesh; scumbles give the wall its faint, living grain. The painter’s discipline is almost musical—few notes, perfectly placed.

Modern Resonance

Strip the figures of biblical identities and the scene remains legible: an adult roused softly by a child at night, a lamp between them, a book open, a task to remember in the morning. Many viewers know this choreography—the tender wake-up to news, the bedside advice, the gentle hand that keeps panic away. De la Tour, by reducing the event to universal gestures, gives the story durability beyond doctrine. It becomes a picture of how good messages travel: in light sufficient for calm, through touch that honors, at a volume the heart can bear.

Conclusion

“Appearance of Angel to St. Joseph, also called The Song of St. Joseph” is de la Tour’s hymn to the small way truth arrives. Composition arranges a corridor for a whisper; light operates as messenger and proof; color sustains a humane temperature; gesture conducts a music of offering and awe; texture persuades the senses that the world is trustworthy; space protects the exchange with silence. Nothing is superfluous. Everything carries the same quiet purpose: to show how vocation begins, not with thunder, but with a hand lifted toward a flame and a face turning, slowly, into its warmth.