Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

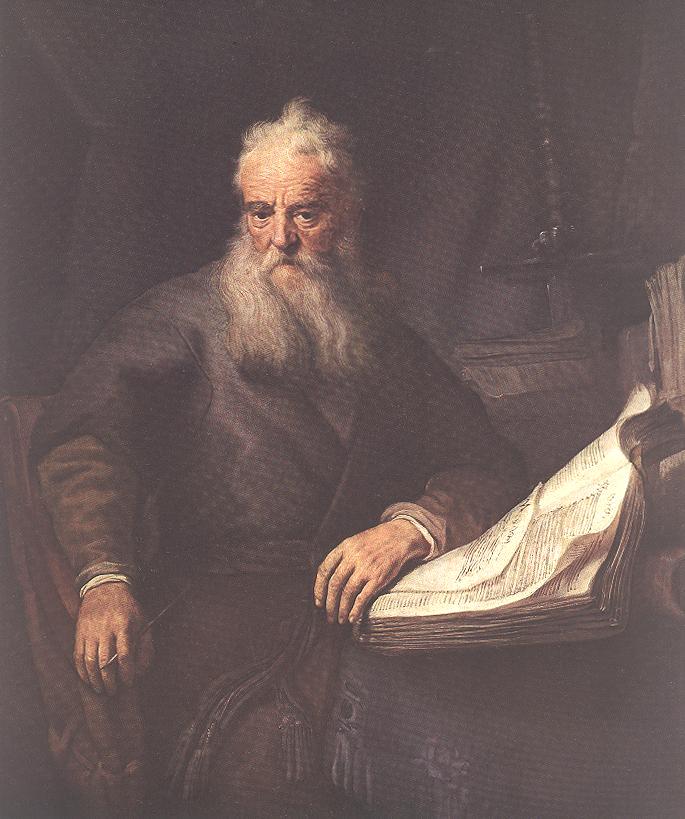

Rembrandt’s “Apostle Paul” (1635) is a meditation on thought made visible. An elderly figure sits in a dim interior, his long beard flowing like a river of light, one hand resting on the edge of an enormous open book. The eyes do not pose; they reckon. The whole painting feels like a pause between sentences—a moment when a writer lifts his gaze from the page to test an idea against conscience. With restrained means—warm, earthen color, a pool of illumination, and hands that look learned rather than heroic—Rembrandt turns doctrine into a human presence. The result is not a pageant of sainthood but an encounter with a mind at work.

Historical Moment and Artistic Purpose

Painted in 1635, the work belongs to Rembrandt’s first flourishing years in Amsterdam. He was newly famous for biblical dramas and for portraits that could grant their sitters both public dignity and private life. In this period he increasingly explored apostles and evangelists as thinking, feeling people rather than distant icons. The subject of Paul—missionary, letter-writer, converted persecutor—offered an ideal conduit for that ambition. Where earlier artists emphasized apostolic authority with armor of symbols, Rembrandt privileges the intellectual labor through which faith meets the world: reading, writing, pausing, and judging.

Subject and Iconography

Paul is traditionally identified by a book or scroll to indicate his letters, and by a sword referencing the “sword of the Spirit” and his martyrdom. Rembrandt chooses the book as the dominant attribute, letting it almost overwhelm the table’s edge with its bulk and pale, scumbled pages. The sword is not displayed as a gleaming emblem; if present at all, it recedes into the murk of the setting. This choice shifts emphasis from militancy to ministry, from outward sign to inward work. Paul’s robe is simple, the surrounding objects spare. Everything that might distract from thought is reduced to shadow.

Composition and the Architecture of Pause

The composition hinges on a diagonal that runs from the upper left—where the saint’s head emerges from darkness—down across the beard and forearm to the illuminated book at lower right. This vector is countered by the horizontal of the table and the quiet verticals behind him, producing a stable geometry that holds the sitter even as his mind travels. The left hand anchors the torso to the chair, its broad knuckles planted, while the right hand, closer to the book, is more relaxed, as if it has just released a page. The pose is neither theatrical nor slack; it is the posture of someone who knows how to sit through long hours of reading without spectacle.

Light and the Theater of Consciousness

Light in this painting is not generic. It behaves like a moral force. It comes from above and in front, bathing forehead, beard, and the open folio. The eye is the darkest part of the lit face, a reminder that insight often happens in the shade of outward brightness. The book is the brightest object in the room, its pale pages catching light the way a river catches sky. That luminous paper becomes the second protagonist. It confirms the saint’s vocation and reflects light back into his face, visually articulating the conversation between text and thinker. Darkness gathers around the periphery not as menace but as privacy; thoughts need quiet.

Color and Material Presence

Rembrandt limits his palette to warm browns, umbers, and reserved lead whites, with discreet cools in the shadows. The economy makes every chromatic shift count. Flesh has a rosy undertone that survives beneath the beard’s veil of grays; the robe absorbs light like worn wool; the table edge gleams with a varnished tone that hints at age and use. He varies paint handling according to material: bearded wisps are laid with soft, lifted strokes; the folio’s edges are built with drier, nearly chalky scumbles; garments gather in deep, translucent glazes. This orchestration gives the scene tactile credibility—one can almost feel the drag of the page under the fingertips.

The Book as Image Within the Image

The open volume is massive, its gutter deep, its margin wide. The lines of script are indicated rather than transcribed, but their rhythm convinces the eye. The perspective is slightly tilted so the viewer can scan the spread as Paul would. It is not an ornament; it is a workstation. Its whiteness becomes a field where light is tested and reflected. By giving the book so much space, Rembrandt asserts that theology is not abstract authority but a lived practice—words weighed by a person responsible for them.

Hands, Beard, and the Physiology of Thought

Few painters use hands as eloquently as Rembrandt. Here the left hand is broad and firm, its veins rising as if the pressure of reflection had migrated into the flesh. The right hand, resting near the book, shows gentler articulation: first finger slightly lifted, thumb relaxed, a posture ready to turn a page or tap a line. The beard is not a halo but a diary of time, its strands catching light in uneven clumps that speak of years spent more in study than in grooming. The face itself bears the record of work: furrowed brow, tightened mouth, eyes whose focus pulls the viewer into the painting’s interior conversation.

Psychology and Narrative

The painting does not illustrate a single biblical episode. It constructs a moment that could belong to many: Paul drafting a letter, recalling his conversion, wrestling with doctrine, preparing to teach. The text’s brightness and the eyes’ depth create a rhythm of reading and reconsidering. You sense that something on the page has troubled him—not with distress, but with the complicated joy of difficult clarity. The narrative is therefore cognitive rather than pictorial. It unfolds not in the world but in the mind, and the viewer is invited to witness that unfolding.

Relationship to Dutch Devotional Culture

Rembrandt’s Amsterdam was a city of readers. Bibles, psalters, sermons, and printed broadsheets circulated quickly. Images of solitary study resonated with Protestant attention to scripture and conscience. Yet Rembrandt avoids strict confessional rhetoric. His Paul is not polemical; he is humane. The painting honors the Protestant ideal of direct encounter with text while suggesting a universal truth: serious faith is thinking faith. In a culture wary of ostentatious sanctity, Rembrandt offers an apostle whose holiness looks like responsibility.

Space, Silence, and the Ethics of Restraint

The setting is deliberately unassertive: a curtain, a table, perhaps the vague geometry of a window or shelf, all swallowed by shadow. The silence of this environment allows small details to sound louder—the glimmer on a page edge, the slight shift of a sleeve. This restraint signals respect. The picture does not blare its subject’s importance; it allows importance to grow by itself through concentration. Even the textiles refuse glitter; they absorb light like good listeners.

Technique: Ground, Glazes, and Edges

Technically the painting shows Rembrandt’s early mastery of layered construction. A warm ground breathes through the shadows, especially in the robe and background. Over this, mid-tone underpainting captures large volumes, and successive glazes deepen the chiaroscuro. Key highlights—nose ridge, cheek, beard tips, page edges—are touched with opaque, buttery paint that sits slightly forward on the surface, catching actual light and reinforcing illusion. Edges are modulated to control attention: crisp where the page meets the shadow, soft where the beard merges into the chest, barely there along the far sleeve. The variety keeps the eye alert and the space believable.

Dialogue with Earlier Apostolic Imagery

Traditional images of Saint Paul, especially in Counter-Reformation art, often present him heroic and frontal, sword aloft, the drama writ large. Rembrandt’s version answers from another register. He trades rhetoric for introspection, combat for conscience. The choice aligns with northern traditions that valued scholarship and moral deliberation. Yet Rembrandt’s interpretation is not bookish in a dry sense; it pulses with life because it is grounded in a body that breathes, rests, and thinks. He preserves the grandeur of apostleship but relocates it inside.

The Role of Age

Age is palpably present: the white beard, the slackened eyelids, the mass of the hands, the pace of the body. Instead of diminishing the apostle, years dignify him. Wisdom in this image is not youthful brilliance; it is the sediment of experience. Rembrandt knows that the credibility of doctrine in the world depends on the credibility of the person speaking it. By painting an old Paul whose intensity remains undiminished, he argues that moral authority ripens.

The Viewer’s Position

The painting assumes a viewer a few feet away—close enough to read the posture of the hands, far enough to feel the enclosing quiet. The angle of the book allows us to meet the text as if invited, yet the apostle’s turned gaze keeps us from reading over his shoulder. We are not intruders; we are witnesses kept at a respectful distance. This carefully staged access fosters empathy without voyeurism.

Time Suspended

The work is built around a held breath. Nothing moves, yet everything is charged: the page that will soon turn, the hand that will return to the margin, the mind that will produce a sentence. Rembrandt stretches this second so we can examine how thought occupies a human body. In that duration lies the painting’s spiritual claim. Revelation, in his telling, is not a flash from nowhere but a patient wrestling that takes place in time.

Material Metaphors

Objects in Rembrandt often serve as quiet metaphors. Here, the heavy folio suggests the weight of tradition; the thick paper edges are like strata of accumulated commentary; the threadbare robe hints at a life spent on essentials. Even the curtain contributes: drawn back just enough, it creates a private chamber without sealing off the world. These details murmur rather than shout, allowing viewers to discover meanings the way Paul discovers sentences—slowly, attentively.

Influence and Legacy

Images of scholars in their studies were popular in the seventeenth century, but few have the moral heat of this painting. Later artists looking to portray intellectual or spiritual labor—philosophers, scientists, writers—found in Rembrandt’s approach a precedent for combining gravity with intimacy. The work also foretells his later, even deeper portraits where dramatic incident disappears and the human face becomes a landscape of experience. “Apostle Paul” is thus both a product of its time and a seed of what would follow.

Why the Painting Still Feels Contemporary

Modern viewers recognize the posture: the pause over an open book, the gaze turned inward, the hand resting on the edge as if to keep one’s place. In a world ruled by speed, the painting defends slowness. It suggests that thinking is an embodied act, that wisdom has weight, and that the tools of understanding—light, paper, attention—are humble. The canvas does not offer decorative spirituality. It offers a way of being present to difficult truth.

Conclusion

Rembrandt’s “Apostle Paul” transforms a saint into a companion in thought. The picture discards spectacle in favor of the drama of reading and considering, using light to bind face and page into a single operation of mind. Hands anchor the body; a book anchors the vocation; darkness protects concentration. Within this crafted stillness we meet a figure whose authority grows from patience rather than pose. Nearly four centuries later, the painting’s quiet holds. It invites us to sit with Paul as he weighs words, and to measure our own attention against the same steady light.