Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

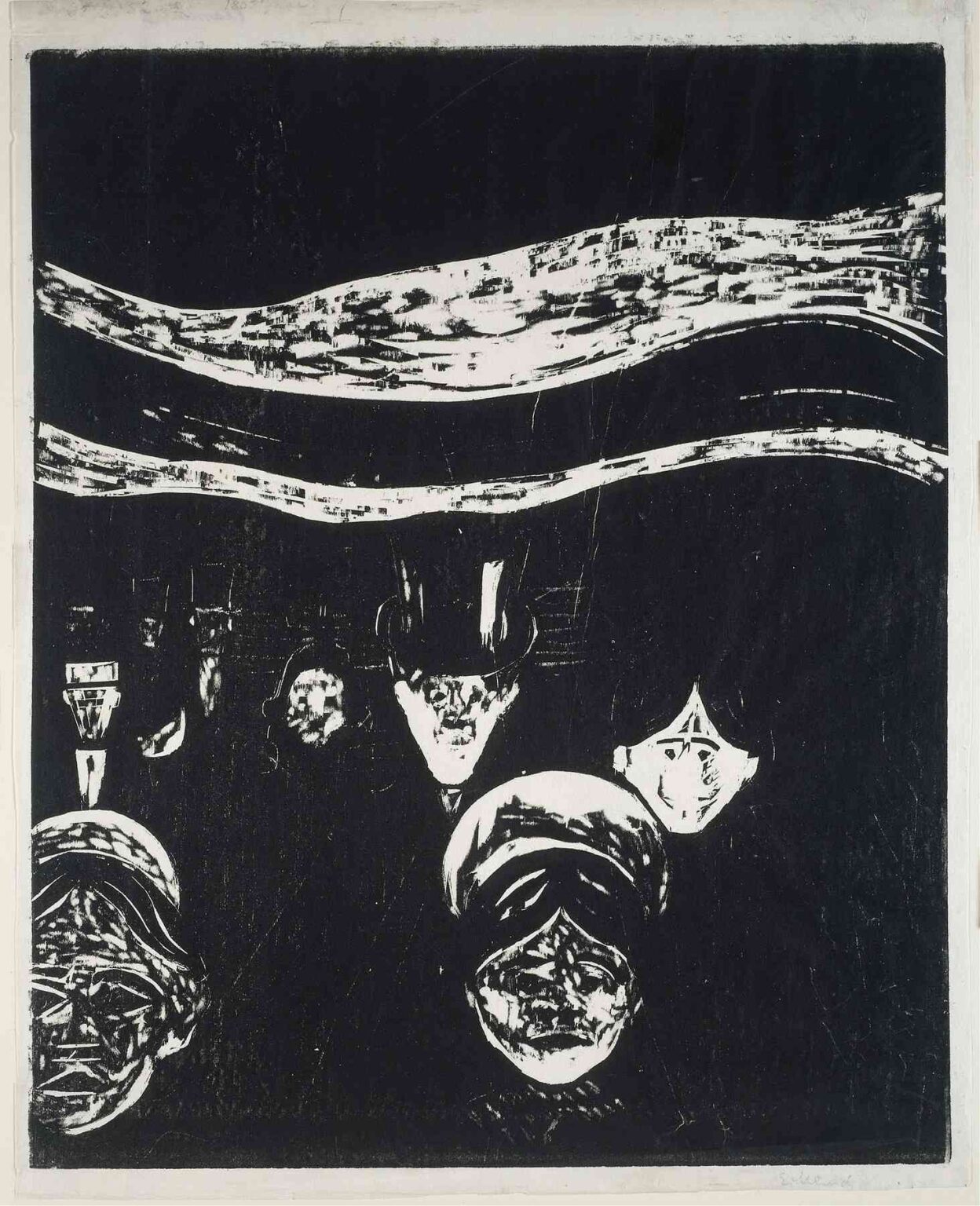

Edvard Munch’s woodcut Anxiety (1896) stands as one of the artist’s most searing visual articulations of collective emotional distress. Executed during the height of his Symbolist period, this work channels the pervasive unease of fin-de-siècle Europe through a deceptively simple yet profoundly unsettling graphic design. Stripped of color, the black-and-white contrasts of the relief print underscore the raw psychological tension at its core. At the turn of the 20th century—marked by rapid industrialization, social upheaval, and Munch’s own experiences of personal loss—Anxiety emerges as both a mirror to wider cultural anxieties and a deeply personal outpouring of inner turmoil. Through an exploration of its historical context, compositional structure, thematic resonances, and technical innovations, this analysis will demonstrate how Anxiety embodies Munch’s conviction that art must lay bare subjective sensation.

Historical and Biographical Context

In 1896, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) was at a critical moment in his career. Already renowned for The Scream (1893) and graphic series exploring love, death, and existential dread, he was deeply embedded in European Symbolist circles. Munch’s early life was marked by tragedy: his mother died of tuberculosis when he was five, and his beloved sister Sophie succumbed to the same illness a decade later. These losses fueled his lifelong preoccupation with grief and anxiety. By the mid-1890s, Munch had settled intermittently in Kristiania (now Oslo) and Berlin, exhibiting with the Berlin Secession and forging connections with avant-garde artists. It was in this climate of intellectual ferment—and as the social and political tensions of Europe mounted—that Munch turned increasingly to printmaking, creating woodcuts and lithographs that could convey his most urgent emotional statements with immediacy and force.

Position within Munch’s Oeuvre

Anxiety belongs to Munch’s Frieze of Life cycle, a loosely organized series of paintings and prints investigating the interplay of love, fear, and death. Where earlier works such as Love and Pain (1894) and Madonna (1894–95) explore eroticism and mortality, Anxiety shifts focus to collective emotional experience. The motif of multiple faces—seen also in Anxiety’s companion print Melancholy III (1899)—underscores the social dimension of inner states. Compared to the solitary figure in The Scream, here Munch portrays a crowd, suggesting that anxiety is not only a personal affliction but a shared atmosphere. This collective focus prefigures aspects of Expressionism: artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde would later adopt Munch’s graphic language to convey the tumult of modern life.

Composition and Spatial Organization

At first glance, Anxiety appears virtually abstract: undulating white bands at the top half of the print evoke a curling horizon or restless sky, while the lower half features a dense gathering of faces emerging from deep black. The human forms occupy the center and bottom third, their skull-like features carved in striated white lines that float against an inky void. Munch arranges the figures in overlapping clusters, their heads pressing into one another, as if seeking refuge in proximity yet unable to escape the oppressive energy that binds them. The horizontal white bands above can be read as echoes of the water in The Scream, linking the two works thematically. The effect is to juxtapose restless natural forces with a piling up of human distress, suggesting that external upheavals and internal anxieties feed each other.

Use of Line and Contrast

The power of Anxiety stems largely from Munch’s masterful handling of relief print techniques. By carving away negative space, he leaves behind raised surfaces that print as white against the inked block’s black fields. The white carvings of the faces—roughly hewn, with jagged edges—appear spectral against the nightmarish black backdrop. Vertical and diagonal scratches in the black ground convey a trembling kinetic energy, as though the scene vibrates with unease. In the bands above, Munch uses a combination of broad gouges and fine scratch marks to suggest clouds or wind-blown air. The stark polarity of black and white intensifies the work’s emotional charge: there is no middle ground, no respite from the extremes of light and dark, reflecting the absolutism of panic and dread.

Symbolism and Thematic Elements

Anxiety operates on multiple symbolic levels. The writhing faces—eyes hollowed, mouths slack or grimacing—conjure a spectrum of fear: from stunned shock to anguished lament. Their anonymity (no individual features stand out) universalizes the experience; these could be any number of people caught in a singular moment of dread. The swirling bands above suggest natural or cosmic forces—storms, waves, or even seismic tremors—encroaching upon the group. This interplay evokes the fin-de-siècle preoccupation with the uncanny and the dissolution of boundaries between self and environment. Munch saw anxiety as a force that “passes through nature,” a scream not only of humanity but of existence itself. Anxiety thus becomes an allegory for the pervasive unease of modernity.

Psychological Dimensions

Munch identified himself as an “expressionist” before the term was codified: he sought to portray the subjective rather than the objective. In Anxiety, he externalizes the physiological and emotional signs of panic through visual metaphor. The clustering of bodies, their indistinct masses merging into one another, speaks to the contagiousness of fear—how one person’s dread begets another’s. The absence of a discernible horizon or escape route traps both viewer and figures in the same oppressive environment. Psychologically, the print engages with early psychoanalytic ideas: anxiety as an upheaval of unconscious forces, surfacing uncontrollably. The disorienting spatial flattening—no clear foreground or background—further destabilizes the viewer’s sense of reality, mirroring the dislocation felt in acute anxiety.

Technical Innovations in Woodcut

Munch’s approach to woodcut in Anxiety diverged from traditional methods. Rather than striving for precise line work, he embraced the medium’s capacity for spontaneous, textured surfaces. He employed large gouges to remove broad areas of wood, creating the sweeping white bands, while using fine chisels or knives to render the intricate facial details. After inking, he sometimes wiped back the surface unevenly, allowing stray white flecks to appear in the black areas, enhancing the sense of disintegration. The large sheet size—often over 60 by 50 centimeters—further distinguishes Anxiety from typical smaller prints, demanding a monumental block and a rigorous printing process. These technical choices underscore Munch’s ambition to make woodcut a medium for major, emotionally resonant statements, rather than a humble reproductive process.

Relation to “The Scream” and Other Works

While The Scream captures a moment of individual terror against a swirling landscape, Anxiety amplifies and communalizes that terror. Both utilize bold contour lines and expressive distortions, yet Anxiety dispenses with color entirely, relying on a binary palette to heighten impact. In The Scream, Munch’s brushwork conveys both organic motion and emotional upheaval; in Anxiety, his carved lines translate that same energy into relief form. Together, these works form the twin pillars of Munch’s exploration of dread: one intimate, the other collective. In later prints such as Facade (1898) and Jealousy (1895), Munch continued to probe psychological states—social critique and interpersonal tension—but Anxiety remains pivotal for its raw, universal reach.

Reception and Critical Legacy

When first exhibited, Munch’s graphic works provoked mixed reactions. Some critics found the raw emotionality and distortive power of his prints alarming or “too Germanic” for Norwegian tastes. Yet avant-garde circles in Berlin and Paris embraced them for their pioneering spirit. Over the 20th century, Anxiety has been recognized as a forerunner of Expressionist printmaking and as a seminal statement on collective angst. It has been cited in discussions of art and trauma, the visual culture of fear, and the representation of mass psychological states. Contemporary exhibitions of Munch’s work frequently juxtapose The Scream and Anxiety to illustrate his dual focus on individual and collective emotion. Art historians credit Anxiety with expanding the possibilities of woodcut and affirming Munch’s role as a pioneer of 20th-century Expressionism.

Conservation and Provenance

Original impressions of Anxiety are held by major institutions including the Munch Museum (Oslo), the Museum of Modern Art (New York), and the British Museum (London). Conservationists note the delicacy of the thin Japanese-style papers Munch favored; over time, impressions can become brittle or suffer minor losses along the edges. The deep, saturated black inks can fade if exposed to excessive light, so prints are typically displayed under subdued illumination. Technical studies using infrared reflectography and spectral analysis have documented Munch’s carving and inking techniques, guiding conservators in maintaining the integrity of impressions from different blocks or states. Provenance records trace early impressions through private collectors in Norway and Germany before their acquisition by public museums in the early 20th century, reflecting the immediate impact and high demand for Munch’s graphic work.

Broader Cultural Significance

Anxiety transcends its era to speak to universal human conditions that resonate in modern times: collective panic, social unrest, and the hidden tremors of the unconscious. Its imagery has surfaced in popular culture—from film to graphic novels—as a visual shorthand for mass dread and existential crisis. In psychology and psychiatry, the print has been referenced in studies of panic disorders and group anxiety, illustrating the physical and emotional contagion of fear. Social scientists have used Anxiety to discuss the concept of social panic and moral contagion in times of crisis. Even in digital culture, the stark contrasts and swirling lines of Anxiety have inspired designers creating visualizations of data anxiety—for instance, stock market crashes visualized as waves. The print’s enduring relevance testifies to its power to encapsulate feelings that defy easy representation.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch’s Anxiety (1896) stands as a masterpiece of emotional expression and technical innovation in relief printmaking. Through its bold contrasts, spectral faces, and dynamic abstractions, the work externalizes the inner tremors of collective fear—both personal and cultural. Situated within Munch’s Frieze of Life and his broader engagement with Symbolism, Anxiety complements and amplifies the individual terror of The Scream, forging a graphic testament to the human condition at a time of profound change. Over a century later, its imagery remains potent, its lines still quivering with the echoes of unease that pass through nature—and through ourselves.