Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

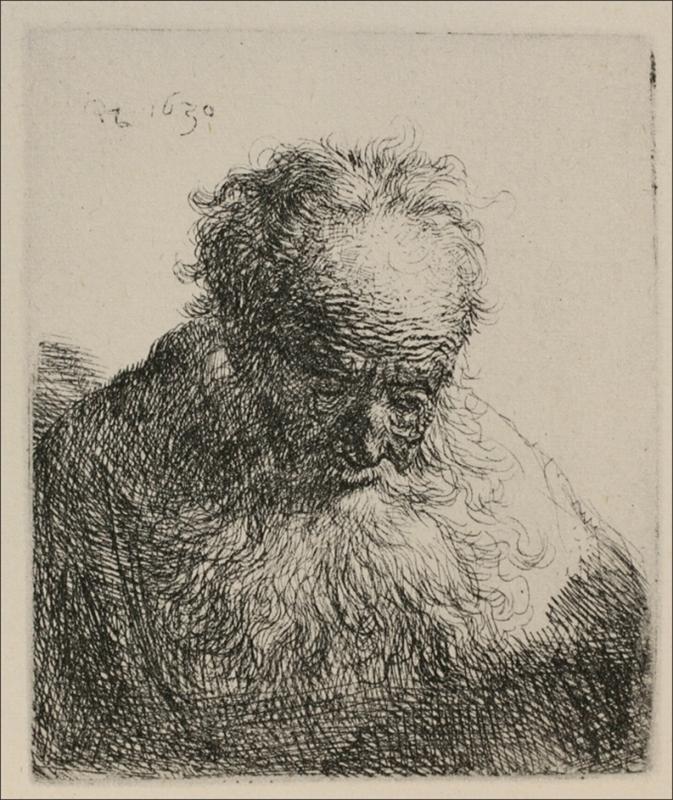

Rembrandt’s “An Old Man with a Large Beard” (1630) is a small etching that opens onto a vast interior world. The head bows forward, eyes cast down, the bald crown catching a faint glimmer while the features sink into a knitted dusk of line. From that penumbra pours a generous beard, a cascading terrain of curls and loops that seems to gather the light of the page and release it slowly. There is almost no setting. The space around the figure is mostly white, as if air itself were the subject. With the slightest means—etched line and untouched paper—Rembrandt makes a study of age, inwardness, and the gentle authority of light.

Historical Context

The year 1630 places this print squarely in Rembrandt’s Leiden period, when he was in his early twenties and relentlessly experimenting with both painting and printmaking. He had recently returned from Amsterdam, where his time with Pieter Lastman sharpened his sense for dramatic narrative and chiaroscuro. Back in Leiden he explored tronies—heads in character—rather than commissioned portraits. These works, intended for the open market, allowed him to probe expression and surface without being tied to likeness or social rank. “An Old Man with a Large Beard” belongs to this exploratory cluster and stands alongside companion studies of elders, beggars, and scholars in which the face becomes a laboratory for light and feeling.

Etching as Rembrandt’s Thinking Tool

Unlike engraving, which requires laborious incision with a burin, etching lets the artist draw freely on a waxed copperplate. After the needle exposes the copper, the plate is bitten in acid to create ink-holding grooves. The process records the hand’s speed, pressure, and hesitation with remarkable fidelity. In this print Rembrandt exploits that responsiveness to build different zones of experience: dense cross-hatching for shadowed fabric and shoulder, loosely woven curls for the beard, short, taut strokes around the eye sockets and bridge of the nose. The lines never feel like a formula; they behave as decisions unfolding in time. The print reads as thought made visible.

Composition and the Geometry of Inwardness

The figure fills the lower two-thirds of the plate, his head leaning into the page from the left. The sloping diagonal from crown to beard directs the gaze downward, while the broad swath of clean paper on the right offers a counterweight of openness. A small wedge of hatched tone behind the left shoulder pushes the silhouette forward, but the rest of the background is silent. This asymmetry is crucial: it gives the head space to breathe and makes the old man’s introspection feel like the center of gravity in a larger, quiet world.

Light as Carver and Consolation

Rembrandt’s light is both sculptor and mood. A soft illumination grazes the bald crown, slides down the brow, and breaks across the ridge of the nose before dissolving into the beard. Because etched lines build darkness, the brightest zones are actually untouched paper. That whiteness reads not as glare but as tender permission. The face is revealed enough to be present and withheld enough to keep its privacy. The light does not interrogate the sitter; it keeps him company.

The Beard as a River of Time

The title emphasizes the beard, and rightly so. Rembrandt turns it into a living topography. At the cheeks the curls are tight and shadowed; farther down they loosen into long, open loops that admit more paper white. The result is a sense of motion—time flowing outward from the face and relaxing as it goes. The beard becomes the print’s light reservoir: where the head retreats into cross-hatched dusk, the beard gleams. In a simple inversion, age is made luminous rather than heavy.

Facial Topography and the Ethics of Looking

The features are economical but specific. A few short hatchings articulate the furrows of the brow; the eyelids sag with believable weight; the nose is shaped by a single firm highlight along the bridge and a pocket of shadow at the tip. There is no theatrical grimace or emblematic frown. The bowed head can be read as fatigue, concentration, prayer, or simple rest. By refusing to overstate emotion, Rembrandt honors the sitter’s interior life. The print models an ethics of attention: intimacy without intrusion.

Line, Texture, and the Vocabulary of Surfaces

Every surface receives its own language of marks. Skin is described by short, slightly irregular strokes that suggest pores and the soft give of flesh. Hair is all loops and wisps, the rhythm of the hand allowed to show. The shoulder and cloak become a thicket of crossings that compress value without turning muddy. This differentiation is not mere virtuosity. It gives the viewer a tactile map: smooth here, wiry there, dense below, breathing above. The eye travels by touch.

Paper White as Space and Breath

The untouched paper to the right of the head is not empty background; it is active atmosphere. It keeps the figure from crowding the frame and gives the gaze somewhere to rest. The white also participates within the beard, glittering between the loops and lending the hair a soft, airy buoyancy. Rembrandt understands that light is not something you draw, but something you allow. The power of the print depends on how carefully he preserves that reserve.

The Signature as Compositional Note

In the upper left, a small monogram with date sits lightly on the page. It balances the hatched wedge below and helps stabilize the top of the composition without competing with the head. The signature’s restraint underscores the modesty of the whole enterprise. This is not a grand pronouncement; it is a quiet event in the field of vision, and even the assertion of authorship respects that quiet.

Relationship to Tronies and Market Culture

As a tronie, the print was not bound to a patron’s identity. It could be purchased by collectors who valued character studies and the virtuosity of etched line. The Dutch art market encouraged such small prints, which were affordable, portable, and intimate. Within that market, Rembrandt’s heads of elders offered something distinctive: not comic types or moral emblems, but complex interior states captured with a candor that invited slow viewing. “An Old Man with a Large Beard” exemplifies that appeal. It gives buyers the sensation of proximity to a person rather than to a story.

Comparisons Within the 1630 Suite of Elders

When placed beside Rembrandt’s other 1630 prints—such as “An Old Man with a Beard,” “An Old Man with a Bushy Beard,” and seated or walking figures—the consistencies and variations emerge. The bowed head recurs, as does the preference for open backgrounds and for beards as light-catching forms. Yet each plate solves the equation differently. In this one the emphasis is on the crown’s glow and the beard’s airy spill, whereas others anchor the face with denser cloak textures or add a staff, chair, or brazier to stage action. The suite constitutes a meditation on age as a set of physical negotiations: how to carry weight, how to conserve warmth, how to grant the eyes rest.

Printing Variants and Atmospheric Choice

Etchings live multiple lives through their impressions. A plate wiped clean leaves the background paper brilliantly white, amplifying the halo on the crown; a light plate tone left on the surface can veil the field with gray, making the head feel more enveloped. Heavier inking deepens the cloak and eye sockets, while a lighter pull lets the beard shimmer. These variables are not afterthoughts; they are part of the work’s expressive range. The same copper can narrate different weathers—clear morning, overcast afternoon—while preserving the core mood of inwardness.

Lessons for Draftsmen and Painters

Artists studying the print can extract practical principles. Reserve large fields of paper to represent light rather than trying to draw it. Model a bald head with minute shifts of value, not with a hard contour. Vary the direction and tightness of hatching to separate materials: soft tissue, wiry hair, felted cloth. Keep accents—inner eye corners, bridge of nose, lip edge—small and decisive. Distribute density so that mass gathers where weight sits, leaving other areas to breathe. Most of all, trust omission. Suggest more than you describe, and let the viewer’s eye complete the form.

The Psychology of Downward Gaze

The eyes look down into the beard’s pale thicket, which means the subject and the viewer share the same luminous field. We follow his gaze but find no object, only the white page. That shared objectlessness is profound. It places us alongside the sitter in a moment of unpurposed attention—neither reading nor praying nor measuring, just letting time settle. The print thus becomes a mirror for quiet states of mind, a device for inviting stillness in the viewer.

The Music of Hatching and the Time of Looking

The print rewards being read like a score. The cloak murmurs in low, even crossings; the beard lifts into a higher register of looped notes; the crown flickers with delicate, airy scribbles; the few strokes at left sound a soft introduction before the main theme—the face—enters. The pacing of these marks governs how long the eye lingers and where it rests. The image is made not just of lines but of durations between them, and those durations are where feeling gathers.

Age Without Allegory

In earlier traditions, the aged male head often stood for philosophy, prophecy, or biblical authority. Rembrandt prunes away such explicit allegory. The old man here is not posed as a saint or sage. He is simply himself, seen with tenderness and accuracy. That ordinariness is revolutionary. It declares that the face of age needs no emblem to be meaningful. Lines, light, and attention are enough.

Condition, Scale, and Intimacy

The small format encourages the viewer to hold the print close, to enter its hush. Any slight wear in the paper or faint plate edges only heighten the tactile sense of an object touched by time. Because Rembrandt builds the head through clear value decisions rather than fragile effects, the image remains robust even as impressions age. The scale matches the subject: a private headspace rendered for private viewing.

Legacy and Continuing Appeal

The enduring magnetism of “An Old Man with a Large Beard” comes from its blend of graphic bravura and human modesty. Collectors admire the virtuoso handling of line, yet what lingers is the mood: the way light strokes the skull, the way the beard seems to breathe, the way the eyes rest without closing. The print is at once intensely specific—a certain head in a particular tilt—and widely resonant, an image of inwardness recognizable across cultures and centuries.

Conclusion

With almost nothing—inked lines and reserved paper—Rembrandt builds a complete world of light, texture, and thought. The bowed head is carved by illumination rather than by contour; the beard gathers and releases brightness like a slow current; the open field around the figure becomes the air of contemplation. As part of his Leiden explorations, “An Old Man with a Large Beard” shows the young artist already fluent in a language of empathy and economy. It asks for quiet looking and returns that quiet in kind, turning a small sheet into a deep, human space where time, attention, and grace meet.