Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

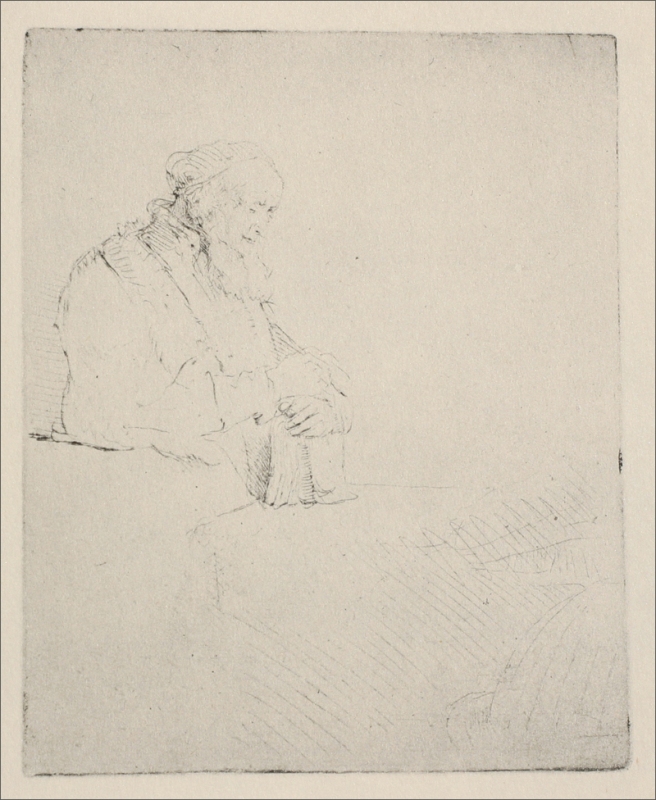

Rembrandt’s “An Old Man Resting his Hands upon a Book” (1645) is among the most radical of the artist’s late-etching meditations on age, thought, and silence. At first glance, it seems scarcely finished: the figure dissolves into the blankness of the plate, the table is only suggested by a few oblique strokes, and vast areas of paper remain untouched. Yet the more one looks, the more the image gathers force. The old man, seated quietly with fingers nested on the upright spine of a thick volume, becomes a portrait of attention itself—attention that has ripened into humility. With almost nothing but contour and breath-light line, Rembrandt invents an entire room of air around a mind at rest.

The Radical Economy of the Plate

The etching is built from near-weightless marks. Rembrandt draws the bent head with a handful of strokes that barely graze the copper: a sloping forehead, the hollow of an eye socket, a short curve for cheek, a beard that descends in feathery notations. The cap and furred collar are indicated by delicate, parallel scratches that thin out as they approach the light. The hand is a masterpiece of abbreviation—several decisive arcs and a few shaded hatches that become knuckles and finger joints. Everything else is omission. In a century that prized labor and finish, Rembrandt’s refusal to fill is audacious. He trusts the viewer’s eye to complete the unspoken volumes, and in that trust the print acquires a hushed authority.

Negative Space as Subject

Most of the sheet is unmarked paper. Far from emptiness, this expanse acts as the living space of the sitter’s thought. The old man floats against it as if in a field of concentrated quiet; the book rises through it like a small island of solidity; and the faint cross-hatching in the lower right reads as the gentlest suggestion of table plane. The negative space also governs rhythm. Our gaze travels from the small cluster of signs that is the head to the next cluster that is the hand and book, and then out into the broad silence surrounding them. The experience mirrors the act of thinking—attention that gathers, releases, and gathers again.

Gesture, Gravity, and the Meaning of Rest

The title points to a gesture: hands resting upon a book. Rest here is not idleness but poise. The palms settle without weight, fingers lightly stacked as if to steady the object that has steadied the mind. The old man is not reading; he is living with what he has read. The downward tilt of the head, the closed or lowered eyes, and the barely indicated mouth suggest a simple stillness rather than exhaustion. Rembrandt resists theatrical emotion; he holds the figure in the calm that scholarship or prayer sometimes grants, when thinking folds back toward gratitude.

The Book as Axis of World and Self

Books populate Rembrandt’s studio pictures, etched scholars, and painted philosophers. In this plate, the book functions both as prop and as axis. Upright on its spine, it becomes a column around which the composition turns. As an emblem, it can be Scripture, law, or the long accumulation of human learning; as an object, it is leather, paper, stitching—things made to be used, worn, and trusted. Because the book is drawn with more density than almost anything else in the print, it carries unusual solidity. The old man’s hands secure their weight upon it, and we feel the reciprocity: text supports person; person safeguards text.

The Physiology of Age in a Few Lines

Rembrandt’s compassion for age is famous. Here he evokes frailty and dignity without resorting to caricature. The cap covers a head whose hairline recedes; the cheek is gently fallen; the beard, though sparely etched, hangs with soft gravity. The shoulders broaden under a heavy garment, then recede into omission. The slightly curved back and lowered chin speak of years without insisting upon pathos. These are not lines designed to advertise the draughtsman’s skill; they are lines that listen to the body.

Light Without Chiaroscuro

Unlike many etched scenes from the same decade, this plate rejects dramatic chiaroscuro. There is no blackness to wrestle with, no torchlit theater. Instead, light comes from everywhere and nowhere at once, a high, diffuse illumination suggested by the mere absence of tone. The face receives the most attention; the hands and the book receive the second; everything else is warmed by reflected brightness. Such open light communicates intellectual clarity and ethical transparency. The sitter does not burn with revelation; he dwells in understanding.

Printing Variations and the Breath of the Plate

Impressions of the print vary widely. Some are wiped very clean, leaving the background almost pristine; others preserve a veil of plate tone that lends the sheet a pearly atmosphere. That plate tone transforms mood: a clean wipe reads as crisp daylight; a toned impression suggests afternoon shadow and the drowsy air of a study. Rembrandt embraced this variability, treating each pull from the press like a slightly different hour. The print, like the mind it pictures, breathes.

The Composition’s Architectural Clarity

The old man sits high and left in the rectangle. That asymmetrical placement leaves space for the book to anchor the lower middle register and for a pale field to open on the right. The faint diagonal hatchings in the lower right corner carve a plane that recedes away from the viewer; the left edge picks up just enough contour of shoulder to prevent the figure from floating. The overall architecture is simple and generous: a vertical stack of head, hand, and book set within a spacious room of paper. One could place a compass point on the knuckles and watch the whole sheet revolve.

Comparison with Rembrandt’s Scholar Prints

Placed beside Rembrandt’s popular etched “Philosopher Reading” or “St. Jerome in a Dark Chamber,” this plate seems nearly ascetic. Those works deploy windows, candles, niches, and elaborate surfaces to dramatize intellect. “An Old Man Resting his Hands upon a Book” does the opposite. It subtracts furniture, shadow, and anecdote until only the essentials remain: a person, a book, and time. The subtraction is not poverty; it is refinement. In removing surround and spectacle, Rembrandt protects the inwardness of the sitter, allowing reflection to appear as a sufficient subject.

The Ethics of Looking

The print places the viewer at a respectful distance. We stand slightly below the sitter and to his right, far enough to keep his privacy intact. The lack of eye contact reinforces that etiquette. We witness without demanding performance. Rembrandt engineers this distance through omission: there is little detail to invade, no crisp texture to pry at. The more we look, the more we are moved to quietness ourselves, matching the visual tone of the sheet with our own attention.

Costume, Texture, and the Tactile Quotient

Despite the spareness, the image is sensuously alive. The furred collar is rendered by a series of small, feathery marks that invite the memory of touch; the cap’s ribbing is registered by parallel lines that the eye reads as wool; the hand, though barely modeled, carries knuckle and tendon. The book’s spine exhibits short, dark hatching that compresses into convincing thickness. These few textures are enough to produce a tactile quotient that keeps the abstraction of the composition grounded in bodies and things.

Time Suspended, Not Stopped

The scene is still, but it is not frozen. Rembrandt’s line retains a quickness that suggests the model shifted slightly as the artist drew, that the light changed, that the mind moved. The slanting strokes on the tabletop grow longer toward the right, implying the sweep of an arm or the trace of the needle’s last pass. Above the sitter’s head, faint pinpricks of tone speckle the blank field like dust in a sunlit room. Time is present as quiet drift.

Possible Identities and the Value of Anonymity

The figure has been variously labeled scholar, rabbi, philosopher, or simply old man. The ambiguity is productive. Without an identifying attribute beyond the book, the image becomes a portrait of thinking as a human possibility rather than a prerogative of any one profession or creed. The man could be a village elder, a retired merchant, a teacher of law, or a grandfather pausing over a family Bible. The anonymity universalizes what is most specific: a mind reconciled to the company of a book.

Spiritual Resonance Without Iconography

Although there is nothing overtly religious in the sheet, many viewers sense a devotional atmosphere. The hands upon the book echo the posture of prayer; the downward gaze suggests inward address; the generous light feels like patience made visible. Rembrandt often created such secular-sacred hybrids—images that allow religious reading without requiring it. Here, study and piety intermingle as shared disciplines of attention.

The Drawing Mind and the Drawn Mind

“An Old Man Resting his Hands upon a Book” is as much self-portrait of Rembrandt’s way of drawing as it is portrayal of the sitter’s thought. The artist reduces means to the minimum necessary, trusting sight to the point of bravery. He removes all flourish that might flatter the hand at the expense of the subject. In doing so, he invites the viewer into the experience of making: a few cautious marks, a pause, a return for one more contour. The print stages a meeting between two contemplations—the old man’s and the artist’s—both of which ask the viewer to slow down.

The Dutch Taste for Quiet Interiors

Seventeenth-century Dutch art is famous for its domestic interiors and for its moral interest in everyday restraint. This plate participates in that culture by dignifying an ordinary room and an ordinary posture. No marble, no pomp, no heraldic noise intrudes. The old man’s cap and fur may suggest modest comfort, but not luxury. The book could be as common as a family Bible or as personal as a notebook. The image models a republic of attention in which dignity is measured by steadiness rather than display.

A Poem of Hatching

Where tone appears—in the lower right corner and on the book’s fore edge—it behaves like poetry: controlled, enjambed, and lightly stressed. The slanted lines lean together without heavy cross-work, their spacing irregular enough to keep the surface lively. Rembrandt’s hatching always obeys form, but here it also obeys silence. It never darkens the sheet beyond the threshold of calm. Like a whispered verse, it closes the distance between viewer and subject.

Why the Image Feels Contemporary

In a world saturated with images that insist on our attention, this print offers an alternative economy: a surplus of quiet. Its minimalism anticipates later aesthetics that prize negative space and unfinished edges. Its moral tone—gentleness, concentration, humility—speaks to contemporary longings for depth amid distraction. Perhaps most current is its ethics of reading. The hands do not clutch the book for argument; they rest upon it as upon a friend.

Conclusion

“An Old Man Resting his Hands upon a Book” (1645) demonstrates how a few lines, placed with love, can hold an entire philosophy of seeing. Rembrandt empties the plate until the essentials—head, hands, book—glow with the light of attention. The man’s rest is that of a life lived in dialogue with words; the artist’s rest is that of a hand that knows when to stop. Together they produce an image that honors thinking as a form of peace. Stand before it, and the sheet slowly teaches the viewer to breathe, to listen, and to trust that what is most human can be said quietly.