Image source: wikiart.org

A Living Giant on Paper

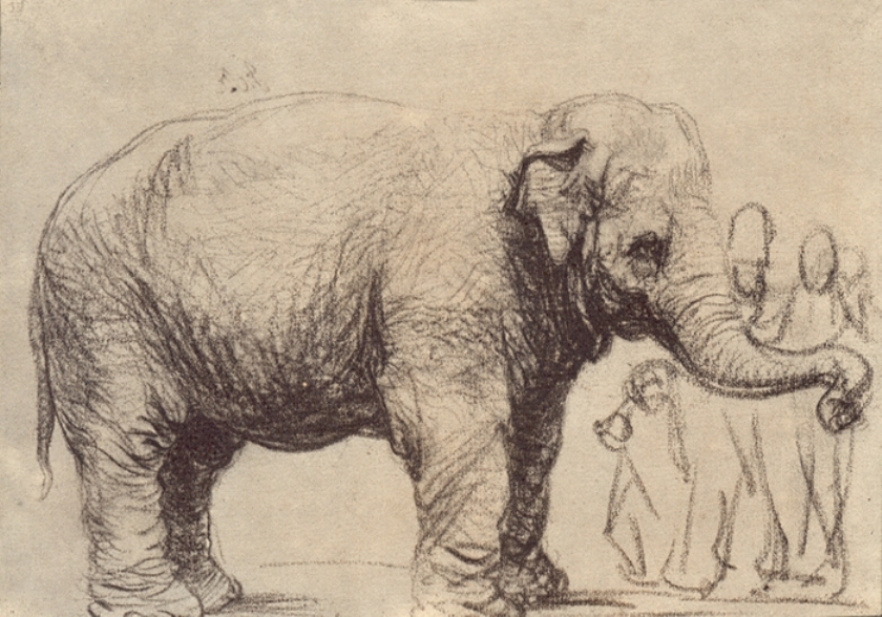

Rembrandt’s “An Elephant” of 1637 captures a singular moment in European art: a Dutch master standing before an animal that most of his contemporaries would only know from travelers’ tales and emblem books. Drawn from life, the subject is almost certainly Hansken, the famous Sri Lankan elephant who toured the Low Countries in the seventeenth century. Rather than staging a spectacle, Rembrandt gives us an intimate encounter. The paper becomes a paddock; the line, a tether between artist and animal. The result is a study that feels both tender and monumental, an image less about strangeness than about shared presence. In an era of maps and marvels, he renders the elephant not as a marvel but as a body—weighty, wrinkled, breathing, balanced on four columnar legs that press into a minimal ground line. The drawing’s power lies in its seriousness: the artist’s decision to meet the unfamiliar with patient observation.

Drawing, Notating, Thinking

Although often discussed alongside paintings, “An Elephant” is a drawing—most likely in black chalk and ink—where every mark functions like a note in the artist’s field journal. Rembrandt does not merely describe contours; he thinks in hatching. Short, angled strokes map the hide’s corrugations, while denser shadow beneath the belly articulates sag and mass. A softer network of lines around the head and ear communicates the supple thickness of skin. The medium’s economy is part of the meaning. Where a painter might model form in glazing, the draftsman must choose exactly where to spend ink and where to leave paper. In those choices we sense Rembrandt’s priorities: the trunk’s slow arc, the softly folded ear, the slight bend of a front knee carrying weight forward. Gaps and overlaps—what drawing manuals call pentimenti—record the eye adjusting in real time. The animal stands still, yet the line is alive.

A Composition of Gravity and Grace

The sheet’s design is deceptively simple: the elephant fills the left two thirds, turned right; a faint ground line steadies the creature; a cluster of light figure sketches on the far right completes the scale. The balance of heavy mass and open space is exquisite. Rembrandt resists the temptation to center the animal. By setting the elephant slightly left and letting the trunk reach toward the margin, he generates a gentle tension, as if the creature is about to make contact with the viewer’s space. The diagonal of the trunk counters the horizontal of the back, creating a crosscurrent that sends the eye from head to tail and back again. Remarkably, the image breathes. The blank background is not an absence; it is a field of quiet that sets off the density of the body. The drawing proves a lesson in how to stage a large form without clutter.

The Science of Skin

Elephant skin is a world of micro-topographies: creases, folds, puckers that vary by region of the body, strain of muscle, and age. Rembrandt studies this with topographic attention. The hatching patterns change direction as if following invisible meridians. On the flank, diagonal strokes crisscross to suggest thick, overlapping folds; around the knee, the lines curve, indicating flesh compressing over a joint. Lighter, more open strokes on the back indicate a smoother, stretched surface; darker compression beneath the belly conjures weight and gravity. This is not a generalized “texture.” It is a cartography of stress points in living tissue. By calibrating line-weight and spacing, he converts abstract marks into a physiology lesson. That precision allows empathy: the animal’s wrinkles are not caricatured but respected, a record of a life lived under great mass.

Light Without Illusionism

There is no strong, directional light source in the conventional studio sense. Instead, Rembrandt uses a tonality of line. Areas of heavier hatch function as shadows; unworked paper plays the role of soft illumination. The elephant appears lit from everywhere and nowhere—a solution that suits a drawing made quickly, likely outdoors or in an unfamiliar interior. This ambient logic avoids theatrical chiaroscuro and keeps attention on volume. The head is the brightest and most consciously modeled zone, the better to focus the viewer on the animal’s face, eye, and the subtle inflection at the base of the trunk. The overall effect is a truthful, low-contrast atmosphere, befitting a study whose aim is comprehension rather than drama.

The Trunk as a Sentence

The trunk, hinged between eye and ground, reads almost like a sentence in cursive. Its arc begins with a downward swing, curves forward, and ends in a little hook, as if punctuated by a comma. That punctuation is important: it suggests motion paused, a gesture temporarily held for the artist. The trunk’s tip coils around an indistinct object—perhaps a prop from the handler or simply a natural curl that keeps its musculature engaged. Anatomically, Rembrandt attends to the trunk’s segmental rings, yet he reduces them to a few crisp notations rather than piling detail on detail. That restraint clarifies the trunk’s role as a conductor’s baton, organizing the sheet’s rhythm.

The Head and the Eye

Rembrandt’s animal heads are always portraits, and this elephant is no exception. The small, forward eye is delicately ringed; the temporal region above it bears a net of short hatches that create the sense of a thick, slightly oily hide. The ear droops with credible heft, turning with a shallow shadow inside the cartilage. Importantly, the artist refuses anthropomorphism. The gaze is not “expressive” in the sentimental sense; it is attentive. The elephant appears to be concentrating on the handler at right. That attention becomes contagious. We look where the elephant looks and find, in the sketched humans, the key to scale and social context.

Humans in Outline

On the right edge, Rembrandt provides a chorus of near-schematic human figures. They are minimally developed, almost diagrammatic: ovals for heads, simple tubes for torsos. If the elephant is rendered with “slow lines,” the people are shorthand. This disproportion in finish is not negligence; it is hierarchy. By reducing the humans to counters, Rembrandt intensifies the animal’s dignity and bulk. At the same time, those figures situate the drawing historically. They remind us that elephants entered Dutch visual and urban life as touring curiosities, managed by keepers and framed by crowds. The juxtaposition asks a quiet question: who is observing whom? The people are outlines; the elephant, a presence.

Ground, Weight, and Balance

A single horizonless ground line anchors the composition. It is astonishing how much that lone stroke accomplishes. It fixes the feet, declares the surface under them, and gives the viewer a sense of how the elephant transfers mass through joints and pads. The foreleg’s subtle angle suggests a micro-shift of weight; the hind legs, heavily shaded, feel planted. In life, elephants sway gently even at rest; the drawing preserves that micro-motion. The animal is not a statue but a balancing act of muscle, tendon, and habit. Notice how the belly’s heavy contour dips between the legs, then rises toward the chest—an elegant, unsentimental notation of gravitational pull. The line is knowledge.

From Curiosity to Creature

Seventeenth-century northern Europe inherited a long tradition of depicting exotic animals from textual sources, often flavored by myth. Think of how Dürer immortalized a rhinoceros he never saw, armored in imaginative plates. Against that background, Rembrandt’s elephant feels like a manifesto for the authority of the eye. He moves the subject from emblem to creature. The drawing declines to load the animal with allegory or moralizing captions. It does not stand for chastity, strength, or the East. It stands for itself, a living being occupying space. That shift may sound basic, but it signals a modern attitude: knowledge built from observation rather than received imagery.

A Global Animal in a Local Studio

The elephant’s very presence in Amsterdam in the 1630s was a byproduct of global trade routes linking South Asia, Africa, and Europe. The Dutch Republic’s maritime enterprises brought spices, textiles, and, periodically, living animals. Rembrandt’s sheet is therefore a local artifact of global networks. The drawing compresses vast distances—the Indian Ocean, Middle Eastern caravan routes, European fairgrounds—into a few square inches of paper. Recognizing that geography enriches the viewing. The animal is not a neutral specimen: its journey was long, expensive, and dangerous; its handlers mediated Europeans’ access to it; its performances monetized wonder. Rembrandt’s sober depiction resists that spectacle by focusing on anatomy, yet the social ecology hovers at the sheet’s edge, in those sketched spectators who paid to look.

Process, Practice, and Speed

How long did the drawing take? The freshness of the line suggests brevity. Rembrandt often sketched from life with the speed of a musician taking dictation. He appears to block in the silhouette first, then develop local densities: the belly, the head, the joints. In places, faint earlier contours peek beneath darker corrections. That layering tells us the drawing is a process document. It likely fed into other works—prints or paintings where animal forms make cameo appearances—or it merely satisfied the artist’s hunger to understand forms he rarely could access. Either way, the sheet embodies a studio ethic: learn by looking, refine by marking, trust the hand to find the body.

Comparisons Within Rembrandt’s Menagerie

Rembrandt drew lions, camels, cows, dogs, and horses with similar fidelity. Compared to those sheets, “An Elephant” stands out for its scale challenge. A lion’s rib cage can be grasped in a handful of crossed strokes; an elephant’s barrel demands acreage of paper. Rembrandt solves this by amplifying the difference between sparing and dense passages. The flank becomes a field for hatching experiments; the head, a kernel of nuanced modeling; the legs, pillars scored to suggest folds. His dogs often look domestic, his lions dramatic; this elephant looks contemplative. The mood matters. It steers the image away from theater and toward respect.

The Ethics of Looking

There is a moral intelligence in the drawing’s restraint. Rembrandt records the handlers without caricature, the elephant without sensationalism. He neither exoticizes nor diminishes. The sheet models an ethics of looking at the unfamiliar: attend, describe, withhold judgment. That stance has consequences in art’s broader history. When artists approach the “other”—human or animal—with curiosity rather than projection, representation becomes dialogue. “An Elephant” quietly exemplifies that possibility. The elephant is a subject, not a prop.

The Body as Architecture

Architects of the period loved analogies between buildings and bodies; here the analogy reverses. The elephant is a building—a living vault supported by columns. The arched back, the massive barrel, the columnar legs with flared bases, all read as structural members. Even the trunk acts like a mobile ribbed conduit. Rembrandt grasps that architecture through contour restraint: the back’s line is one of the simplest on the page, yet it holds the entire structure together. When you follow that arc from the withers to the tail, you experience the curve as both anatomy and design.

Silence and Sound

Drawings are silent, but this one hums with imagined sound: the scuff of pads on dirt, a soft exhale, the muted rustle of a drooping ear. Rembrandt leaves ample blank paper around the animal, and that white space acts like acoustic dampening. The quiet is almost reverent. The handlers at the right, sketched like marginal notes, seem hushed by the elephant’s presence. The sheet encourages slow viewing. Time expands to the rhythm of the animal’s breath.

Why the Image Feels Contemporary

Four centuries on, the drawing looks strikingly modern. Its unadorned background, attention to material facts, and trust in the expressive capacity of the minimal mark anticipate later realist and even modernist priorities. One can draw a line from this sheet to nineteenth-century naturalist illustration and onward to twentieth-century studies that value process over polish. Its incompletion is its strength. Viewers today, used to photography’s flood, may find relief in an image that accomplishes so much with so little. The economy of means invites us to meet the animal halfway, to complete it with our own attention.

The Elephant’s Psychology

Can we speak of an elephant’s psychology in a drawing? Only cautiously. Yet Rembrandt, master of human interiority, implies a temperament. The gentle forward tilt of the head, the relaxed yet engaged trunk, the planted feet all suggest calm interest rather than fear or agitation. The animal appears at work but not distressed, in communication with its handler. That reading is supported by the absence of gratuitous whip marks or exaggerated eye highlights. Rembrandt’s empathy does not humanize; it dignifies.

The Sheet as Memory

Because live encounters with such animals were rare in the Dutch Republic, drawings like this became repositories of memory—both the artist’s and the public’s. The sheet keeps a meeting alive long after the handlers and the crowd have dispersed. For the artist, it is a portable archive of forms. For us, it is a time capsule. The paper has browned; the lines have softened; but the presence persists. “An Elephant” thus performs art’s oldest function: to stabilize a fleeting experience for future minds.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin with the silhouette. Notice its rightward lean, the way the trunk’s tip nearly grazes the human group. Step closer to follow a single patch of hatching across the flank; feel how line direction maps surface direction. Pause at the head, reading the subtle turn from forehead to eye to cheek. Drop to the foreleg and sense the stored weight there, the skin’s accordion folds compressing over bone. Then step back again and absorb the orchestration: dense to spare, dark to light, heavy to airy. Rembrandt built the sheet to reward that oscillation between micro and macro views.

A Humane Monument

Many seventeenth-century monuments are literal: arches, equestrian statues, triumphal canvases. Rembrandt’s monument is in graphite and ink. The elephant’s bulk, treated without pomp, becomes a monument to attention itself. The drawing celebrates not empire but encounter. It treats knowledge as an art of care—care with lines, with edges, with facts of anatomy, with the truth of an animal standing in a Dutch yard on an ordinary day. That ethos makes “An Elephant” one of the most quietly radical images of its century.

Legacy and Afterlife

This sheet’s afterlife extends beyond connoisseurship. It helped establish a way of seeing unfamiliar animals that shaped European illustration and collecting. Later artists who drew at zoos, circuses, and menageries inherited its lessons: prioritize structure, modulate texture with hatching, set scale with minimal human figures, let blank paper do atmospheric work. The drawing also contributes to a cultural history of the elephant in Europe, complicating narratives of brute exoticism with one of attentive respect. Its survival invites us to ask how images can free subjects from the roles they are assigned, even when made within the very systems that transported them.

Closing Reflection

“An Elephant” is a small work about a large being. In it, Rembrandt marshals an array of technical decisions—composition, hatching, contour, negative space—to transform a curiosity into a creature and a spectacle into a study. The elephant remains singular, massive, and strange, yet it is also immediately knowable: skin, muscle, weight, balance. The handlers at the right remind us that this knowledge is social and historical, born of contact enabled by trade and performance. But the core exchange here is between one eye and one animal. On that quiet ground, Rembrandt’s humane intelligence flourishes, and a seventeenth-century drawing steps forward with the freshness of now.