Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions

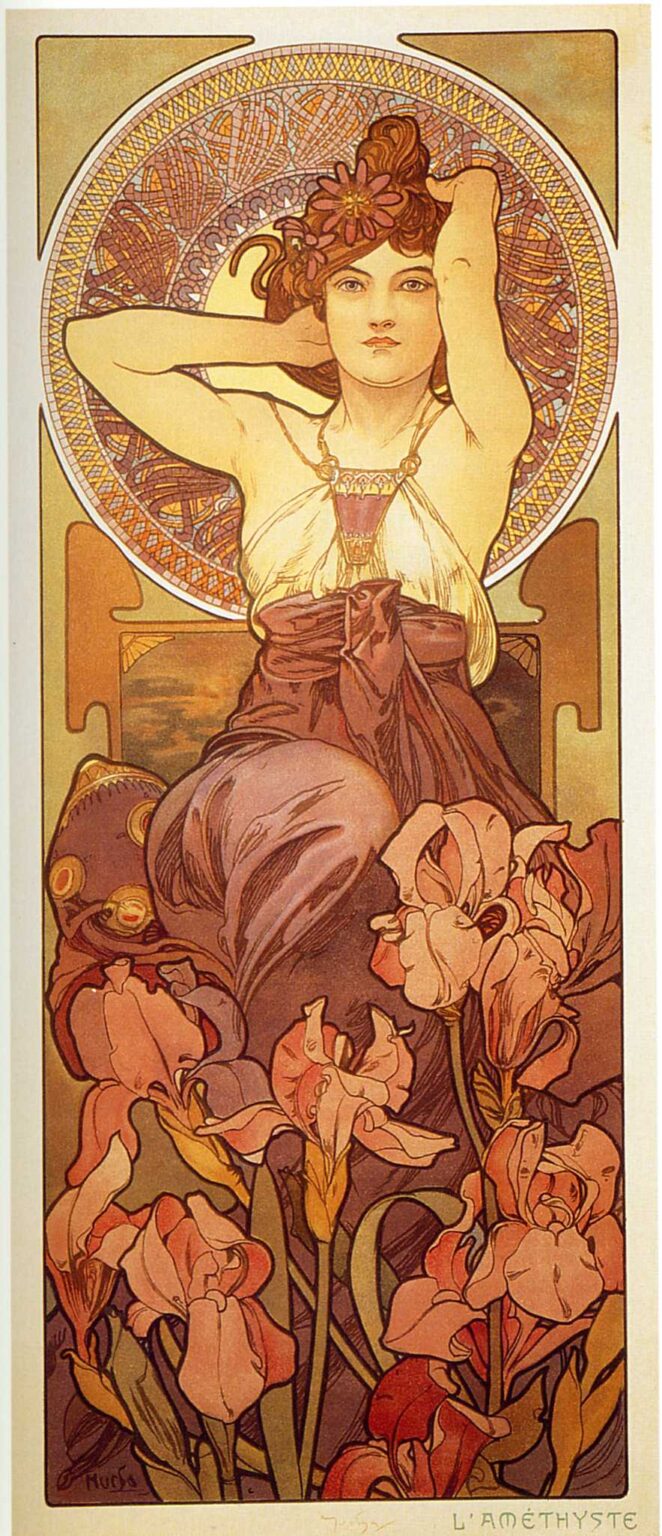

“Amethyst” (1900) greets the eye like a jeweled window. A young woman sits before a radiant circular mandala, her arms lifted to gather her hair as if she has just stepped from a dressing table. Below her, irises rise in a thick, ornamental meadow, their petals curling like ribbons. Violets, plums, and rosy mauves dominate the palette and are warmed by honeyed golds and tawny browns. The composition is at once intimate and ceremonial, an emblem of a gemstone translated into a human mood.

Historical Moment

At the turn of the twentieth century Alphonse Mucha refined a format that blended allegory, fashion, and ornament into decorative panels for modern interiors. “Amethyst” belongs to this flowering moment, when his lithographs turned gemstones, flowers, seasons, and even hours of the day into personifications. The panel embodies the late-1890s confidence that art could live with people at home—affordable, reproducible, and exquisitely designed—while carrying the weight of symbol and style.

Place Within The Gemstone Cycle

“Amethyst” forms part of a group devoted to precious stones, each print presenting a woman whose colors, flowers, and atmosphere echo the qualities of its gem. Where ruby burns and emerald cools, amethyst suggests inwardness, lucid thought, and a violet serenity. Mucha captures that character not by depicting crystals but by orchestrating hue, pattern, and gesture until the panel itself feels faceted with purple light.

Composition And Framing

The panel’s tall rectangle is organized around three tiers: a floral field at the base, the seated figure at center, and a radiant circular halo behind the head. The figure leans slightly forward, her raised arms forming a horizontal bar that stabilizes the vertical thrust. The circular mandala is both halo and architectural window, locking the composition with a perfect counterform to the elongated frame. At the corners, small squared notches quiet the edges and keep the interior world contained. The result is a structure as sound as a colonnade and as airy as lace.

The Mandala As Jewel

Mucha’s circular background is a marvel of lace-like geometry—interlaced lines, lozenges, and cross-hatching that together produce a visual analogy for a cut gemstone. The pattern does not merely decorate; it refracts. Like light bouncing within facets, the small repeating units collect and release color, flooding the figure with a subtle aura. The mandala also dignifies the sitter, translating the sacred halo of medieval art into a secular, decorative divinity.

The Figure And Gesture

The woman’s pose is one Mucha explored repeatedly: arms lifted behind the head, elbows forming a gentle winged span. This gesture lengthens the torso, opens the chest, and frames the face, presenting the model as both human and emblem. Her gaze is steady and frontal but not challenging, the mouth poised in a neutral calm. The lifted arms make space for a cascade of hair pinned with a flower, a visual rhyme with the irises below. The gesture is not theatrical; it is poised, as if composure were the precious stone on display.

Color And The Spirit Of Amethyst

Color does the storytelling. The panel breathes violets and dusty mauves, set against golden tans, moss greens, and the coppery browns of chair and sash. Mucha keeps saturation moderate so that harmony, not contrast, rules the scene. Purples appear in many registers—from plum shadows in the drapery to lilac notes in the flowers—evoking the way a single gemstone can flash multiple tints. The palette feels cool-minded but warm-hearted, a perfect translation of amethyst’s reputation for clarity joined to calm.

Irises And Botanical Symbolism

Irises crowd the lower third with spearlike leaves and petals that curl like tongues of silk. Their forms suit the Art Nouveau line, all whiplash curves and pointed ends, and their traditional associations with wisdom and eloquence reinforce the gem’s character. Mucha renders them not as botanical specimens but as decorative actors. Each blossom turns slightly, the whole cluster reading like a chorus that sings in the key of violet.

Line, Contour, And the Whiplash Motif

Mucha’s line is supple and disciplined. A dark, unbroken contour travels the figure’s silhouette; within that boundary, lighter interior lines articulate drapery folds, hair strands, and the irises’ veins. The famous whiplash curve—long, elastic, and asymmetrical—courses through hair, sash, and petals, yet never becomes indulgent. Line is never mere flourish; it is structure. Because the contours are so sure, the large shapes of flat color can lie calm, producing the velvety surface that makes his lithographs feel luminous without glare.

Drapery And Surface

The central garment binds the waist and drapes over the knees in a slow, sculptural fall. Highlights and darker bands give it the sheen of satin, but the handling remains graphic rather than painterly: folds are simplified into large, elegant shapes, each a discrete plane of color bounded by line. The fabric’s plum tones bridge the violets of the flowers and the warm ground of the chair, anchoring the palette. Drapery becomes architecture, lending the figure ceremonial gravity.

Space And Atmosphere

While the panel is essentially flat in the poster sense, Mucha opens a shallow stage with the chair’s arms and the edge of the mandala. The background is a quiet gradient rather than a descriptive setting, ensuring the eye rests on the emblematic relationship among figure, halo, and flowers. Space is not an environment to inhabit but a calm field in which meaning can be arranged. The atmosphere is therefore both intimate and abstract.

Typography And Inscription

At the base, the inscription “L’AMÉTHYSTE” appears in understated capitals. The letters are clear, evenly spaced, and integrated with the border. Mucha treats text as ornament and pledge—ornament because the letterforms echo the panel’s decorative intelligence, pledge because they name the idea the image embodies. The type does not compete with the picture; it completes it, like a hallmark on metalwork.

Lithographic Craft

“Amethyst” is a color lithograph whose clarity arises from skilled planning. Each hue is printed from a separate stone or plate and must register with the others precisely. Mucha designs with this in mind: broad fields of even tone, crisp edges, and patterns built from line rather than painterly texture. Subtle gradations—on the cheek, along the drapery, within the floral field—are achieved by printing thin veils of color, not by scrubbing pigment. The result is a velvety surface and an optical calm that suits the panel’s meditative character.

Ornament And Order

One of Mucha’s hallmarks is his ability to pour lavish ornament into strict order. In “Amethyst,” the mandala is dense with tiny motifs, yet the overall design remains lucid because the large masses—the figure, the circle, the flower bed—are kept simple. This balance prevents the image from becoming busy. It also models a philosophy of beauty: abundance within discipline, sensuality within geometry. Ornament is the language; order is the grammar.

The Face As Locus Of Meaning

The face is minimally modeled yet intensely present. Eyes meet ours evenly, and the calm mouth avoids coquettish cues. A faint rose warms the cheeks; a golden light brushes the forehead. Mucha avoids strong cast shadows, a choice that keeps the expression open and icon-like. Because the face is set against a radiant mandala, it reads as the gemstone’s living core. The figure is not the owner of amethyst; she is its manifestation.

Relationship To Fashion And Modern Living

The panel belongs to the culture of the modern apartment. It would have hung above a mantel or between windows, its tall format perfect for narrow wall spaces. The costume, jewelry, and hairstyle are contemporary yet idealized, asserting that modern fashion can bear classical dignity. “Amethyst” therefore performs a double function: it adorns a room and proposes a way of being—composed, luminous, inwardly balanced.

Rhythm And Visual Music

Mucha composes like a musician. Long curves of arms, sash, and iris stems establish a legato rhythm. Smaller accents—the flower across the hair, the clasp at the neckline, the bright petal tips—play like ornamented notes over a steady melody. The mandala behind the head is a steady drum of pattern, a quiet ostinato that supports the whole. The eye experiences the panel as a phrase that rises from the flowers, rests at the face, and resolves in the circle’s embrace.

Allegory Without Narrative

No anecdote is offered. There is no story to parse, no myth to recall. The image communicates through equivalences: purple equals amethyst, iris equals wise eloquence, halo equals radiance, lifted arms equal poise. This economy makes the panel timeless and portable across cultures. It is not tied to a specific plot; it is a distilled mood anyone can recognize.

Comparison With Mucha’s Broader Oeuvre

Seen alongside other cycles—seasons, flowers, arts—“Amethyst” displays Mucha’s mature grammar. The raised-arm pose recurs because it creates a regal vertical while leaving shoulders and neck graceful. The floral tier at the base provides a garden of motifs for the line to play in. The circular halo binds the head to the architecture of the page. Yet each subject demands its own key. Here the key is violet, and the chord is serenity.

Why The Image Endures

“Amethyst” remains compelling because it offers a complete sensory and symbolic experience in one glance. It fulfills the promise of Art Nouveau—to weave the organic and the ornamental into daily life—without sacrificing clarity. The figure’s composure models a way of inhabiting the modern world: dignified, attentive, suffused with quiet color. The print’s craft and concept are inseparable; beauty is the method and the message.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Amethyst” converts a gemstone’s character into a living emblem. A poised woman, a jeweled mandala, and a choir of irises collaborate to produce violet calm. Line is music, color is temperament, and ornament is order. The panel exemplifies why Mucha’s images outlived the products and performances they once promoted: they speak in a language of balance and light that still feels at home on our walls and in our days.