Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to “All Souls’ Picture”

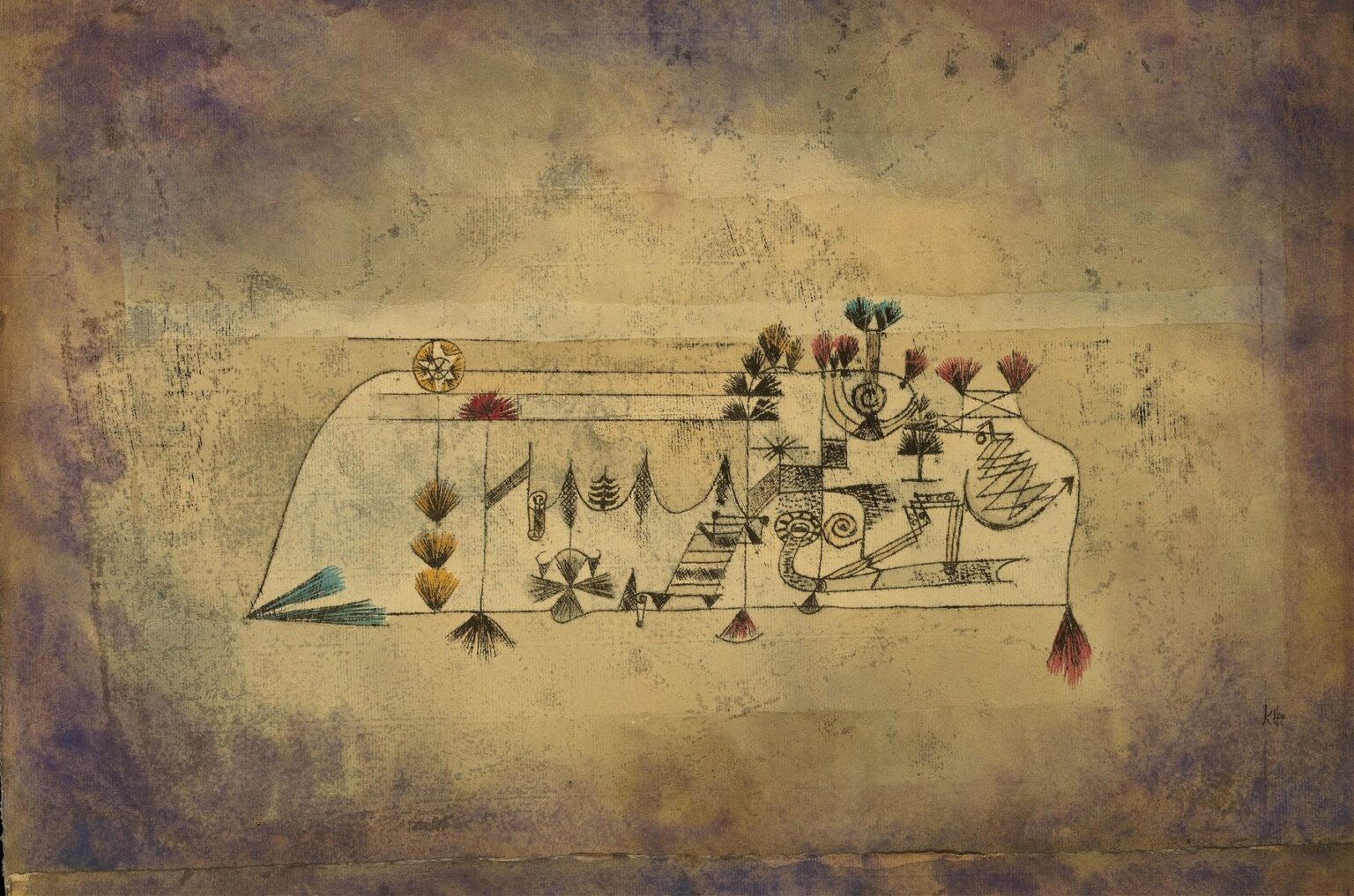

Paul Klee’s All Souls’ Picture, created in 1921, stands among his most enigmatic and evocative works. Rendered in watercolor and ink on paper, the composition features a horizontal array of delicate black linear motifs floating across a softly graded field of ochre and violet washes. At first glance, these motifs resemble a constellation of abstract symbols—stylized plants, geometric forms, and musical notations—suspended in an ethereal atmosphere. The painting’s title suggests a spiritual dimension, inviting viewers to contemplate themes of memory, commemoration, and the invisible connections binding the living and the departed. In this analysis, we’ll explore the historical context, formal strategies, symbolic resonance, and technical execution that make All Souls’ Picture a cornerstone of Klee’s Bauhaus-era masterpiece.

Historical Context of 1921 and Klee’s Artistic Evolution

By 1921, Europe was grappling with the aftermath of the First World War, and artists sought new visual languages to express collective trauma and hope. Paul Klee had joined the Bauhaus faculty in the spring of that year, bringing fresh ideas from his travels in Tunisia and his early Expressionist phase. His teaching emphasized the fundamentals of line, color, and rhythm—concepts he had been refining since his 1914 Arabian journeys. All Souls’ Picture emerges from this pivotal moment when Klee transitioned away from figurative caricatures toward a more abstract, symbolic lexicon. The painting reflects both the era’s existential searching and Klee’s commitment to making art that serves as “a living thing” beyond mere representation.

Artistic Influences and Bauhaus Pedagogy

At the Bauhaus, Klee shared insights with Wassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, and László Moholy-Nagy, contributing to a vibrant exchange on abstraction and form. He drew inspiration from children’s drawings, African and Pacific Islander art, and Goethe’s color theory, all of which informed his hybrid approach. In lectures that would later become the Pedagogical Sketchbook, Klee outlined his belief that line is “a dot moving,” and that color can express musical harmony. All Souls’ Picture embodies these teachings: its fine, calligraphic lines animate the surface as a musical score might, while the layered washes demonstrate a nuanced understanding of color chords and spatial depth.

Formal Composition and Spatial Structure

Klee arranges his motifs in a loose horizontal band slightly above the paper’s midpoint, suggesting a landscape or floating register. This central band is anchored by vertical drips and slender stems that connect geometric shapes—circles, diamonds, spirals—to a common baseline. The field above and below this register is treated with variegated washes: a warm ochre sweep transitions into cooler violet at the edges, framing the linear forms like sky and earth. Horizontal pencil guidelines subtly organize the motifs without strict adherence, maintaining the spontaneous energy of a sketch. This balance of structure and freedom typifies Klee’s mastery of pictorial space, where containment and dissolution coexist.

Analysis of Line Work and Calligraphic Gesture

The black ink lines in All Souls’ Picture range from crisp, straight strokes to wavering, gestural loops. Klee likely employed a reed or steel-nib pen, varying pressure to achieve both sharp angles and delicate curves. Each mark carries expressive weight: the spiral at the painting’s center suggests inward seeking or cyclical time, while the upward-pointing arrows convey aspiration or transition. Clusters of short, radiating lines resemble abstracted botanical forms or distant fireworks, echoing the painting’s spiritual overtones. Through these calligraphic gestures, Klee bridges drawing and writing, proposing that each sudden kink or flourish is a signifier in a visual language of the soul.

Use of Color and Atmospheric Washes

Unlike pure ink drawings, All Souls’ Picture features soft watercolor washes that suffuse the paper with mood. The ochre wash—applied in broad, semi-transparent strokes—evokes dusk or the glow of unseen fires, while violet accents at margins suggest dusk’s enveloping shadow. Klee blended pigments with water and gum arabic to achieve subtle granulation, allowing paper texture to emerge. The juxtaposition of warm and cool hues creates a dynamic tension, inviting viewers to dwell on the space between form and void. This atmospheric treatment enhances the painting’s meditative quality, as if the symbols float within an endless, luminous expanse.

Abstract Symbolism and the “All Souls” Theme

The title All Souls’ Picture alludes to themes of remembrance and the unseen realms of consciousness. In Christian tradition, All Souls’ Day commemorates the departed; Klee’s abstracted glyphs can be read as memorial tokens—flowers, candles, or musical notes offered up in remembrance. The spirals may signify cycles of life and death, while the ascending arrows point toward transcendence. Unlike explicit narrative illustration, Klee’s symbols remain open-ended, permitting personal interpretation. Each motif becomes a fragment of a collective memory, a trace of souls that flicker across the fragile surface like scintillating spirits in twilight.

Interpretation of Central Motifs and Forms

Within the central register, motifs coalesce into thematic clusters. On the left, a circular rosette hovers above stacked triangular sprouts, suggesting new life emerging. At the center, a ladder-like zigzag meets a spiral, evoking both ascent and introspection. To the right, a cluster of radial strokes resembles a grove of stylized trees or candle flames, balanced by a sequence of interconnected diamonds that hint at ritual chains. The horizontal lines tying these elements together can be seen as threads of continuity, binding individual forms into a unified tapestry. Through this orchestration, Klee transforms isolated glyphs into a cohesive visual poem.

Klee’s Integration of Primitive and Modern Visual Languages

Klee admired non-Western art forms and folk traditions for their direct, symbolic power. In All Souls’ Picture, his line work recalls cave paintings, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and African textiles—yet rendered with a modernist economy. This integration positions Klee as a precursor to later artists who sought authenticity in so-called “primitive” sources while forging a new abstraction. By abstracting these influences through his Bauhaus lens, he asserts that all cultures share a basic pictorial grammar, one that can express universal human experiences beyond geographic or temporal boundaries.

Materials, Technique, and Creative Process

Executed on lightweight paper sized roughly 30 × 47 centimeters, Klee’s work reveals his layered process. He likely began with a faint pencil grid to map the composition’s horizon line and key intervals. Next came the pen-and-ink motifs, drawn with quick confidence. Finally, watercolor washes were brushed over and around the drawings, requiring careful timing to avoid disturbing the ink. Occasional reworking—visible in faint erasures and overlapping strokes—indicates Klee’s willingness to refine his initial impulses. The unprimed paper soaks up pigment unevenly, leaving a textured patina that enriches the painting’s atmospheric resonance.

Philosophical and Spiritual Underpinnings

Klee’s philosophical outlook was shaped by anthroposophy, theosophy, and Goethean natural science, all of which emphasized the spiritual dimensions of art. In 1921, he wrote of paintings as entities “alive, with form and movement like living creatures.” All Souls’ Picture embodies this belief: its symbols flutter as if animated, its color field pulsates with unseen forces. The painting can be read as a visual meditation on interconnectedness, the perpetual dance of matter and spirit. Klee’s fusion of formal innovation and spiritual inquiry positions the work as both a modernist experiment and a timeless testament to the artist’s inner vision.

Reception, Exhibitions, and Critical Legacy

While Klee’s renown during his lifetime remained somewhat circumscribed within academic circles, All Souls’ Picture came to be celebrated in postwar retrospectives as a highlight of his Bauhaus period. Critics have praised its seamless blend of line and wash, its evocative symbolism, and its formal coherence amid apparent spontaneity. The painting has been included in major exhibitions from the 1950s onward, appearing alongside other meditative works such as In the Style of Kairouan and Dynamic Hieroglyphics. Contemporary scholars view it as a key example of Klee’s project to synthesize intuition and intellect, art and life.

Conservation and Continued Relevance

Original versions of All Souls’ Picture are preserved in museum collections under strict climate control to protect the fragile watercolor and ink. Conservationists monitor color density, paper acidity, and humidity to prevent fading and deterioration. Digital reproductions and high-resolution imaging have made the work accessible to global audiences, inspiring fresh scholarship on Klee’s semiotic methods. Graphic designers, animators, and visual artists continue to reference its glyph-like motifs and atmospheric washes, adapting Klee’s approach to line and color in diverse creative contexts. The painting’s ability to evoke mystery and contemplation ensures its ongoing relevance in discussions of abstraction and spirituality.

Conclusion

Paul Klee’s All Souls’ Picture remains a landmark of early modern abstraction, where delicate calligraphy meets poetic color in service of a deeply human meditation. Through its harmonized interplay of line, wash, and symbol, the painting transcends literal depiction to become a portal into realms of memory, ritual, and collective consciousness. Nearly a century after its creation, All Souls’ Picture continues to captivate viewers with its ineffable resonance, reminding us that art can serve as a bridge between worlds—visible and invisible, temporal and eternal.