Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

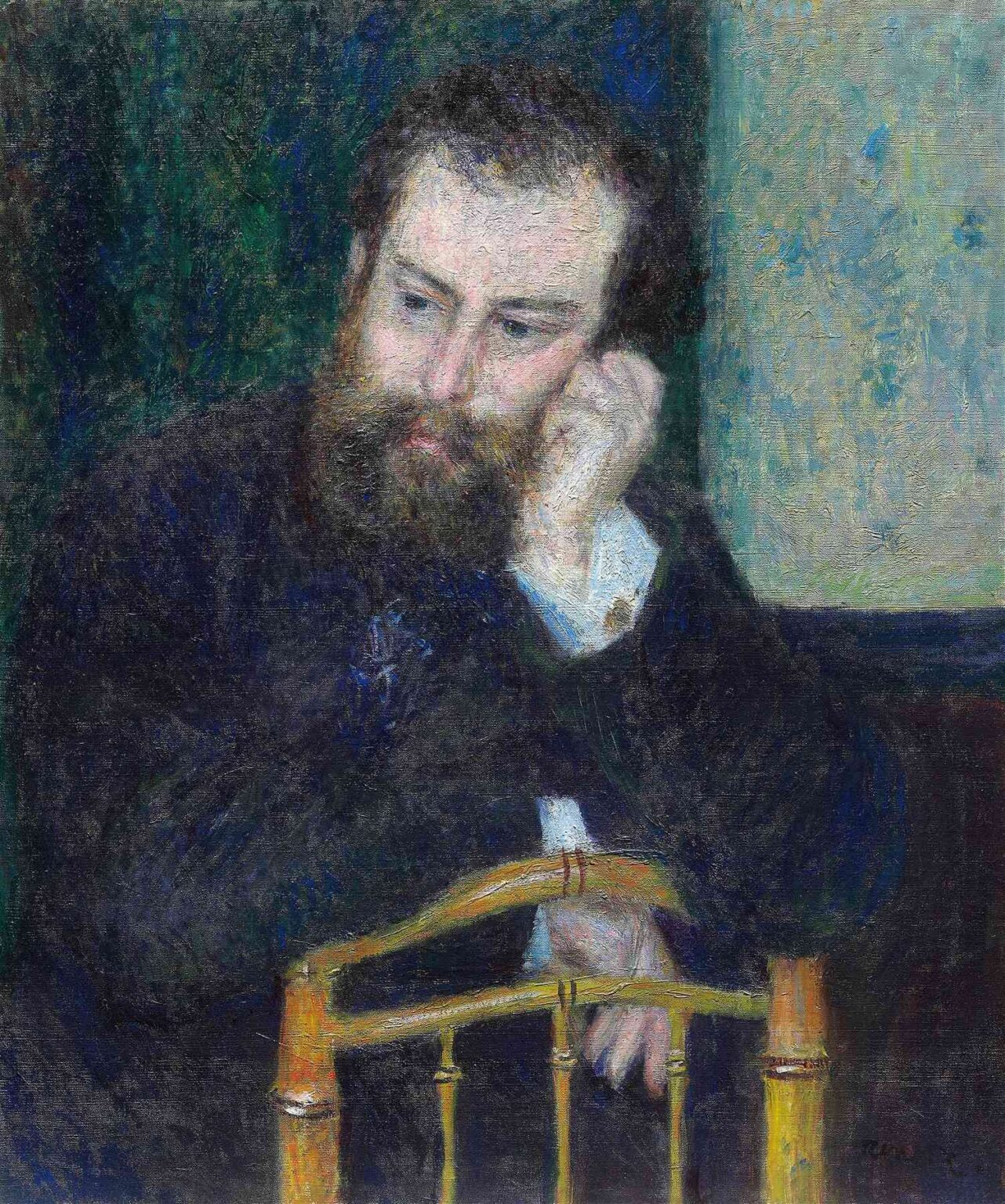

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s 1876 portrait Alfred Sisley offers a revealing glimpse into the camaraderie and mutual admiration among the pioneers of French Impressionism. Depicting his close friend and fellow artist Alfred Sisley seated behind a bamboo‑framed chair, Renoir balances fidelity to the sitter’s likeness with the spontaneous brushwork and vibrant color harmonies that defined the movement. In this 2000‑word analysis, we will explore the multifaceted dimensions of this work—its historical context, compositional strategies, painterly techniques, and emotional resonance—to understand how Renoir crafted a portrait that is both an homage to a colleague and a testament to the evolving language of modern art.

Historical Context of 1876 Paris and Impressionism

By 1876, Paris had become the crucible of avant‑garde innovation. The first Impressionist exhibition—held in 1874—had stunned critics and the public with its unconventional presentations of light, color, and everyday life. Renoir, Claude Monet, Sisley, Camille Pissarro, and others sought independence from the strictures of the Salon, championing direct observation and plein‑air painting. Sisley, a British‑born artist who settled in France, was celebrated for his luminous landscapes. In turning his talents to portraiture of a fellow Impressionist, Renoir situated Alfred Sisley at the intersection of artistic friendship and the broader quest to redefine painting in an era of rapid social and technological change.

Renoir’s Evolution and Relationship with Sisley

Renoir’s own artistic evolution by 1876 had moved from the pointillist experiments of his earliest outings to a freer, more sensuous brushwork. His friendship with Sisley, forged in the camaraderie of outdoor sketching sessions along the Seine, rested on shared convictions about the primacy of light and color. Sisley’s quiet temperament and unwavering dedication to landscape painting stood in contrast to Renoir’s more extroverted social scenes, yet the two artists mutually inspired each other’s work. Renoir’s decision to paint Sisley signals both personal affection and professional respect—an attempt to capture the contemplative spirit of his colleague within the very idiom they had together pioneered.

Subject and Relationship: A Painter’s Portrait of a Painter

In Alfred Sisley, Renoir eschews grandiosity in favor of quiet intimacy. Sisley is shown in three‑quarter view, leaning his head on his hand in a gesture of thoughtful repose. His gaze extends beyond the canvas’s edge, suggesting daydreams or considerations of his next landscape composition. The bamboo chair’s backrest, rendered with warm ochres, both frames Sisley’s form and nods to Japonisme influences circulating in Parisian design. Through subtle nuances of posture and expression, Renoir communicates Sisley’s reflective nature and deep immersion in his art, forging an empathetic connection between sitter, painter, and viewer.

Composition and Framing

Renoir organizes the portrait around a tight pictorial space. The sitter’s torso and head occupy the upper two‑thirds of the canvas, while the bamboo chair delineates a horizontal plane that anchors the figure. A strong diagonal is introduced by Sisley’s arm, guiding the viewer’s eye from the lower left upward toward his contemplative face. The backdrop divides into two contrasting areas—a dark green drapery on the left and a lighter, patterned wall on the right—creating a subtle tension between enclosure and openness. This compositional scheme balances stability with movement, reflecting both the solidity of Sisley’s character and the fluid rhythms of Impressionist painting.

The Language of Color

Renoir’s color palette in this portrait is at once restrained and resonant. Deep greens and blues in the drapery evoke the tonal range Sisley favored in his landscape skies, while the warmer ochres of the bamboo chair and the peach‑toned flesh of the sitter introduce complementary warmth. Sisley’s jacket, painted in muted charcoal and navy strokes, reads as almost abstract at a distance, yet yields to softer modeling upon close inspection. Touches of soft pink on the cheek and hand animate the sitter’s flesh, anchoring the portrait in lifelike presence. Renoir’s orchestration of related hues underscores the harmony between subject and environment, a hallmark of Impressionist color theory.

Brushwork and Painterly Technique

While Renoir’s 1876 portraits retain elements of his more controlled academic training, they also exhibit the rapid, flickering strokes that characterize his mature Impressionist style. In Alfred Sisley, the background drapery is suggested with broad, energetic sweeps, while Sisley’s facial features emerge from a network of shorter, intersecting strokes. The bamboo chair’s smooth form is defined by confident, linear marks, contrasting with the more tactile handling of flesh. This interplay of brushwork techniques—gestural versus precise, layered versus direct—creates a dynamic surface that both acknowledges the painting’s constructed nature and conveys the fleeting effects of light on different materials.

Modeling of Form and Light

Unlike later portraits in which Renoir returned to stronger chiaroscuro, Alfred Sisley demonstrates a softer modulation of light. Ambient illumination appears to fill the room, scattering gentle highlights across the sitter’s forehead, cheek, and hand. Shadows under the brow and along the jacket lapels are rendered in cool blues and violets, accentuating the warmth of the surrounding hues. The three‑dimensional modeling of the face balances fleshy roundness with the intangible quality of quickly captured light. Renoir thus achieves a portrait that feels both immediate—an evanescent moment frozen—and enduring—a carefully considered composition of volume and color.

Emotional and Psychological Depth

Central to Renoir’s success in Alfred Sisley is his ability to convey the inner life of his sitter. Sisley’s slightly furrowed brow and half‑closed eyes suggest a mind at work—an artist perpetually observing and processing the world. Yet there is no anxiety in his expression, only a serene absorption. Renoir’s tender rendering of the hand supporting the face, with its softly modeled knuckles and delicate play of light, speaks to a compassionate gaze. The resulting portrait is not merely a document of physical likeness but an evocative psychological study, inviting viewers to ponder the thoughts and feelings behind the gaze.

The Background: Abstraction and Ambience

In the two distinct background zones, Renoir experiments with abstraction. The deep green panel to the left dissolves into mottled brushmarks that echo forested foliage, perhaps alluding to Sisley’s landscape preoccupations. The lighter section on the right, featuring faint floral or leaf motifs, resembles wallpaper or tapestry, introducing a decorative element that anchors the interior setting. By abstracting these surfaces, Renoir avoids literal depiction, instead using color and texture to create an ambient field that complements the sitter. The background becomes both stage and echo, resonating with Sisley’s own pictorial concerns.

Alfred Sisley’s Artistic Persona

Though primarily known as a landscape painter, Sisley’s presence in Renoir’s portrait reveals the quiet introspection behind his canvases. Renoir emphasizes Sisley’s scholarly countenance—his short beard, his neatly combed hair, his contemplative pose—reminding viewers that the act of painting is as much mental as it is manual. The bamboo chair may hint at the mobility of plein‑air practice, evoking the stretcher‑chairs artists carried into the field. Through these visual cues, Renoir honors Sisley’s dedication to exploring light and atmosphere, while also acknowledging the intellectual rigor that underpinned his aesthetic.

Interaction of Artist and Subject

The rapport between Renoir and Sisley underlies the portrait’s success. Sisley sits in relaxed confidence, trusting Renoir’s brush to convey his essence. In turn, Renoir approaches the canvas with both respect for Sisley’s individuality and the creative freedom characteristic of Impressionism. This mutual trust allows for a portrait that feels both truthful and artful. Viewers sense the underlying friendship—the shared outdoor sketching trips, the lively studio conversations—that informs every stroke. Alfred Sisley stands as a testament to how personal bonds can elevate artistic collaboration.

Legacy and Place in Renoir’s Oeuvre

Alfred Sisley occupies a significant place within Renoir’s body of work. Painted between his earliest Salon successes and his later return to classical modeling, the portrait exemplifies the transitional energy of the mid‑1870s. Its blend of lively brushwork, sensitive coloration, and psychological insight would inform Renoir’s subsequent portraits of friends and family. Moreover, the painting underscores the spirit of mutual support that defined the Impressionist circle. Today, Alfred Sisley remains celebrated for its technical virtuosity and its moving tribute to one of the movement’s gentlest spirits.

Conclusion

In Alfred Sisley (1876), Pierre‑Auguste Renoir achieves a profound synthesis of Impressionist innovation and empathetic portraiture. Through masterful composition, dynamic brushwork, and harmonious color, he captures not just the likeness of his fellow artist but the very essence of Sisley’s contemplative nature. The work stands as both a personal tribute and a landmark in the evolution of modern portrait painting, offering viewers an intimate encounter with two artists united by friendship and a shared vision of light’s transformative power.