Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

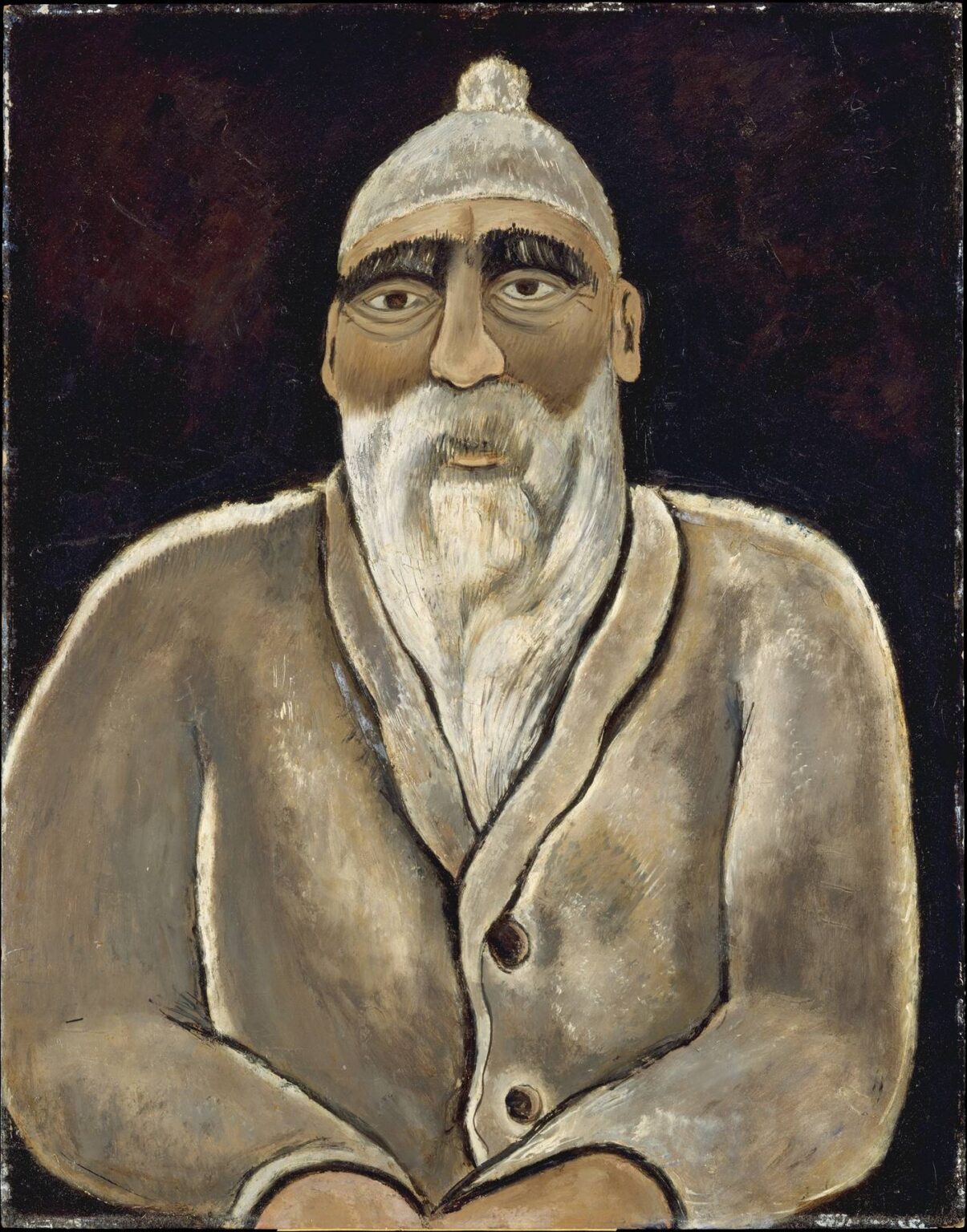

Marsden Hartley’s Albert Pinkham Ryder (1938) stands as a compelling convergence of homage, portraiture, and modernist experimentation. In this painting, Hartley turns his attention from the everyday landscapes and Maine still lifes that dominated his late career to celebrate a fellow American artist. Through a monumental, almost archetypal representation of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917), Hartley crafts a portrait that transcends mere likeness to evoke the visionary intensity and brooding symbolism associated with Ryder’s own work. Executed with Hartley’s characteristic emphasis on shape, line, and muted tonality, Albert Pinkham Ryder invites viewers to consider not only the sitter’s personal narrative but also the larger dialogues between American art traditions and modernist impulses.

Historical Context and Artistic Lineage

Albert Pinkham Ryder was a self‑taught artist whose moody seascapes and allegorical scenes earned him posthumous acclaim as a precursor to American modernism. Dartmouth-educated and largely reclusive, Ryder developed a highly individual style marked by layered impastos and dreamlike compositions. By 1938, a generation after Ryder’s death, Marsden Hartley—himself celebrated for bridging realism, symbolism, and abstraction—sought to honor this overlooked forebear. The late 1930s in American art saw a resurgence of interest in homegrown traditions, fueled by the Federal Arts Project and a burgeoning sense of national cultural identity. Hartley’s portrait emerges within this milieu as both tribute and dialogue: he visually aligns himself with Ryder’s visionary spirit while reinterpreting portraiture through a modernist lens.

Hartley’s Evolution Toward Symbolic Portraiture

Throughout his career, Hartley oscillated between landscape, still life, and portraiture, often infusing each genre with emblematic significance. His early works reveal academic discipline, while his Berlin and Paris periods display Cubo‑Expressionist experimentation. Returning to Maine in the 1930s, Hartley synthesized these influences into a style that balanced representational clarity with abstracted form. In Albert Pinkham Ryder, he applies this hybrid vocabulary to the human figure. The sitter’s simplified contours, flattened spatial setting, and emphatic outlines reflect Hartley’s hard‑won mastery of form. Yet the painting also carries Ryder‑like echoes—somber coloration, textured surfaces, and an aura of introspection—underscoring Hartley’s reverence for his predecessor’s poetic vision.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Hartley composes the portrait as a half‑length figure occupying nearly the entire canvas. The sitter’s broad shoulders, nearly triangular torso, and voluminous coat create a sturdy geometric frame. At the top, Ryder’s knitted cap echoes a sculptural dome, while his downward gaze and sagging eyelids suggest contemplative inwardness. The background is rendered as a deep, nearly black field mottled with subtle bruises of brown and purple, collapsing depth and focusing attention squarely on the figure. The sitter’s arms rest on an implied surface at the canvas’s lower edge, reinforcing the frontal, iconic presence. This conscious flattening and centralization disrupt traditional perspectival portraiture, aligning Ryder’s image with Hartley’s earlier abstract totems and underscoring the portrait’s symbolic resonance.

Palette and Chromatic Resonance

Hartley adopts a muted, near‑monochrome palette dominated by grays, browns, and off‑whites, punctuated only by subtle touches of ochre in the sitter’s face and hands. The muted tones evoke Ryder’s own twilight seascapes, where dusk and shadow hold sway. Ryder’s wool cap and beard are rendered in creamy whites—heavy impasto recalling the foam of storm‑tossed waves—while his weathered features emerge from layers of thinned pigment that allow the underlying canvas to seep through. Hartley’s restrained color choices intensify the painting’s meditative mood, inviting viewers to dwell on the textures and forms rather than chromatic spectacle. This chromatic austerity also situates the portrait within the American modernist tradition of introspective coloration, aligning Hartley with compatriots such as Charles Sheeler and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

The surface of Albert Pinkham Ryder bears the mark of Hartley’s varied brushwork. The coat and cap exhibit broad, confident strokes layered to suggest thick woolen texture, while Ryder’s beard consists of swirling, almost calligraphic lines that evoke both hair and maritime surf. In the facial features, Hartley employs shorter, more delicate strokes to model the contours of Ryder’s cheeks and brow. The background’s rough, rubbed‑in passages create a subtle chiaroscuro that heightens the figure’s relief without distracting from it. Overall, the interplay of thick impasto and thinner washes underscores the painting’s dual identity as both a tangible object and a symbol‑laden image, echoing Ryder’s own tactile approach to paint.

Ryder as Visionary Symbol

By 1938, Albert Pinkham Ryder had acquired mythic status as an isolated genius whose brooding canvases prefigured Abstract Expressionism. Hartley taps into this mythology by rendering Ryder as a stoic visionary. The knitted cap and heavy coat suggest seafaring voyages and exposure to elemental forces, while the deeply hooded eyes and austere expression hint at internal depths and solitary contemplation. In reducing Ryder’s likeness to key archetypal elements—a weathered face, an oceanic white beard, a dark void behind—Hartley universalizes the sitter’s identity, presenting him as a symbol of the artist as outsider and prophet. This treatment aligns Ryder with figures from Hartley’s earlier allegorical portraits—officers, saints, totems—thereby situating them both within a shared lineage of visionary art.

Interplay of Representation and Abstraction

Hartley’s Albert Pinkham Ryder straddles the line between realistic portrayal and abstract iconography. While the sitter remains identifiable through naturalistic features—the shape of his nose, the set of his eyes—the painting’s flattened perspective, simplified shapes, and minimal background dissolve the figure into an emblem. The triangular torso and circular cap recall geometric motifs from Hartley’s pure abstractions, such as Geometric Figure (c. 1940), suggesting an ongoing dialogue between the artist’s figurative and non‑figurative phases. By mobilizing abstraction within a representational framework, Hartley asserts that true portraiture transcends surface likeness to capture deeper psychological and symbolic truths about its subject.

Thematic Reflections on Artistic Solitude and Legacy

Hartley’s homage to Ryder resonates with themes of artistic solitude, perseverance, and the passage of time. Both artists endured periods of underappreciation and personal hardship before gaining critical recognition. Ryder’s reclusiveness and mood‑laden seascapes reflect an inward turn that Hartley himself experienced amid wartime dislocation and expatriate tensions. By painting Ryder in his later years—hat, coat, beard—Hartley underscores the sitter’s survival through storms literal and metaphorical. The nearly black background becomes a metaphor for the abyss from which visionary art emerges. In this way, Albert Pinkham Ryder operates as a meditation on artistic endurance, inviting viewers to contemplate the costs and rewards of creative isolation.

Hartley’s Place in the American Portrait Tradition

American portraiture in the 1930s and ’40s encompassed both realist and modernist approaches, from Thomas Hart Benton’s rasher social narratives to Stuart Davis’s stylized abstractions. Hartley occupies a distinctive position within this spectrum: he embraces direct representation of the human figure while infusing it with symbolic and formal innovations drawn from European avant‑gardes. Albert Pinkham Ryder exemplifies this hybrid stance. It diverges sharply from Regionalist theatricality by adopting spare backgrounds and intensified outlines, yet it remains firmly situated within an American lineage of commemorating national artists. Through this portrait, Hartley asserts the validity of modernist form in depicting American cultural icons, expanding the possibilities of portraiture as a site of aesthetic and ideological exchange.

Reception and Continuing Influence

Upon its initial exhibition, Albert Pinkham Ryder drew attention for Hartley’s bold reinterpretation of an American master. Critics praised the painting’s austere dignity and the painter’s ability to evoke Ryder’s essence rather than a purely physical likeness. In subsequent decades, the portrait has become emblematic of Hartley’s late career and of broader mid‑century efforts to integrate modernist abstraction with national heritage. Contemporary artists exploring the nexus of tribute and transformation—such as Kehinde Wiley and Elizabeth Peyton—echo Hartley’s approach in their reimaginings of historical figures. Albert Pinkham Ryder thus retains relevance as a model of how portraiture can simultaneously honor tradition and propel formal innovation.

Conclusion

Marsden Hartley’s Albert Pinkham Ryder (1938) is a masterful synthesis of homage, portraiture, and abstraction. Through a restrained palette, dynamic brushwork, and geometric structuring, Hartley renders Ryder not merely as a biographical subject but as a visionary symbol of American artistic ascent. The painting’s flattened space and emphatic outlines bridge the artist’s European avant‑garde experiences and his deep engagement with regional identity, forging a distinct modernist vocabulary. In celebrating Ryder’s legacy, Hartley affirms the enduring power of creative solitude and the capacity of portraiture to convey both likeness and myth. As viewers continue to encounter this work, they are invited to reflect on the intertwined destinies of two American modernists and the transcendent potential of art across generations.