Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

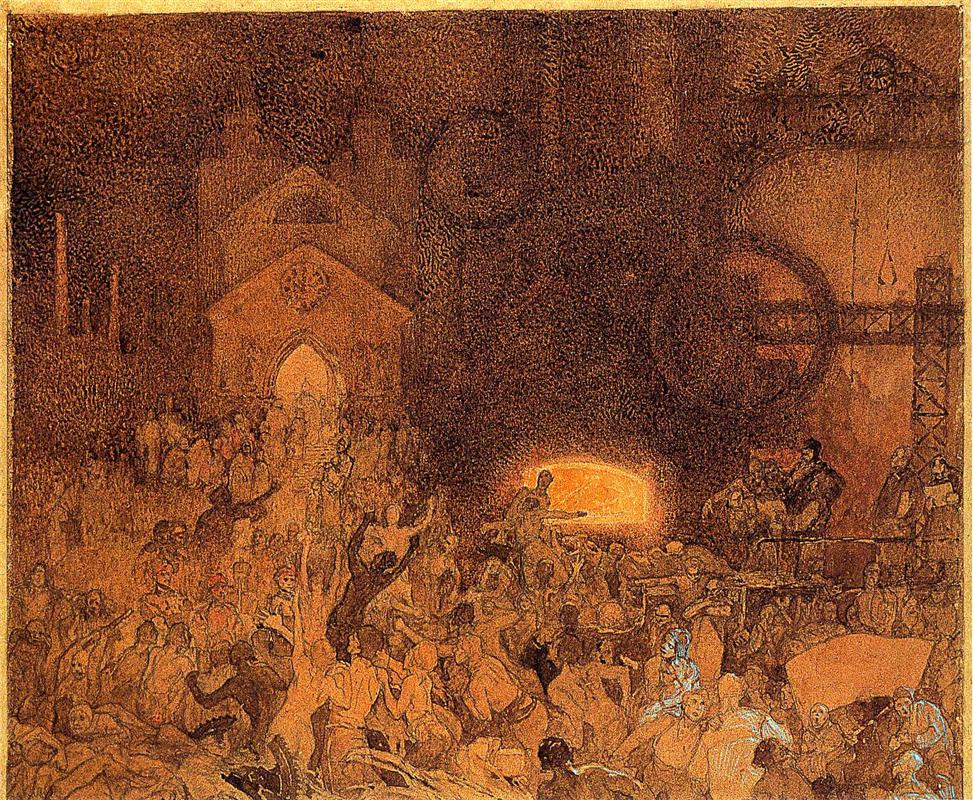

Alphonse Mucha’s “Age of Reason” (1938) is a searing late meditation on modernity. Composed almost entirely in umbers and soot-black tones, the scene compresses a crowd, a church, and an industrial works into a single, churning picture field. At the right, a furnace glows with a hard orange core; at the left, a church façade opens like a pale mouth in the dark; between and beneath them, bodies surge, labor, argue, faint, and strain. The title promises clarity, but the image delivers tension. Reason here is not a tidy theorem. It is heat, negotiation, and risk—an energy capable of forging or of burning, depending on how a society handles it.

Historical Context

Mucha made this work on the eve of catastrophe. By 1938, Europe felt the pressure of rearmament and authoritarian spectacle; Czechoslovakia, the state whose birth Mucha had celebrated, was already under mortal threat. After decades spent narrating Slavic history as a long ascent toward dignity, the artist turned to an allegorical cycle of “ages” to ask what kind of civilization might survive the coming storm. “Age of Love” imagines a civic ritual of tenderness; “Age of Reason” offers the counterweight, staging the modern city as a contest of forces—faith, industry, crowds, spectacle—vying to define what rational life should mean. The sepia, study-like handling underscores the urgency. This is not a polished mural; it is a blueprint for thinking under pressure.

The Architecture of the Composition

The painting is built on a steep diagonal that runs from the blazing furnace at right-center to the bright portal of the church at left. Around these two sources of light Mucha arranges a crescent of humanity. The crowd piles up like surf against the church steps, spills across the foreground, and surges again toward the industrial platform. The upper zone is heavy with darkness punctuated by silhouettes of wheels, cranes, and smokestacks. The composition is a machine for directing attention from one “altar” to the other, making viewers feel the tug between sacred inheritance and technological promise.

The Two Altars: Furnace and Church

Much as medieval painters balanced altar and throne, Mucha opposes furnace and nave. The church’s doorway glows with cool whiteness; its Gothic geometry provides the only stable verticals in the left half of the picture. The furnace is a horizontal mouth, orange and volatile, tended by workers whose gestures echo priestly ministrations. Both spaces are theaters of devotion. In one, faith gathers and disperses the crowd; in the other, heat orders bodies into labor. Reason, the painting suggests, sits uncomfortably on the bench between these altars, useful to both and obedient to neither.

Choreography of the Crowd

Mucha’s crowd is not an indistinct mass. He breaks it into legible knots of action: a cluster presses toward the church; a tangle of bodies heaves upward from the foreground as if pushed by necessity; a line of workers moves in disciplined rhythm at the furnace; watchers perch on scaffolds and railings. Amid the tumult, individual dramas flare—pleading hands, a child hoisted, a fainting figure—each a human syllable in a long sentence. The effect is not chaos but counterpoint. Reason in public life, the image argues, is never solitary; it is a negotiation among many voices, some learned, some desperate.

Tonal Architecture and the Weather of Soot

The palette is almost entirely a scale of browns, from ocher through burnt umber to near black. Within this restricted register, Mucha composes with precision. The brightest tones belong to three things only: the furnace core, the church portal, and a few pale bodies caught by those lights. Everything else is drenched in coal dust. This tonal economy shapes the mood. The age is not luminous; it is smoky. Understanding arrives locally, where people have gathered around a source of heat or a door of meaning, and then disappears into haze.

Line, Texture, and the Engine of Drawing

Under the washes, Mucha’s drawing remains decisive. He scratches and knots lines to make crowds cohere, uses quick arabesques to suggest mechanized parts, and reserves firmer contour for figures at the center of action. The surface reads like a palimpsest—notes, revisions, and emphases layered until the image hums. The technique matches the subject. Reason here is not a polished statue; it is thinking-in-progress, an accumulation of marks in a difficult atmosphere.

Light as Ambivalent Reason

Both of the painting’s lights are ambiguous. The furnace promises warmth, power, and productivity. It also throws a harsh glare, flattening faces and erasing detail. The church portal offers a cooler beacon, a refuge for the eye. It is also a hole into mystery; one cannot see what doctrine or hierarchy waits inside. Mucha refuses to choose between them. The title “Age of Reason” does not endorse a single source of illumination; it asks the viewer to decide how to walk between them without burning or sleeping.

Machines and Bodies

At the right, belts, cranes, and wheels crowd the picture plane. Their scale is deliberately off, looming larger than the men who operate them. The iron seems animated, almost bestial, while human figures appear small and repetitive in the labor line. The left half, by contrast, is dense with flesh—knees, shoulders, outstretched arms—rendered with warmth despite the sepia. Mucha’s moral geometry is pointed: machines are powerful instruments; they become monstrous only when they eclipse bodies. Reason fails when tools become ends.

Ritual, Procession, and the Persistence of Faith

The church is not merely a backdrop. A procession appears to move toward its door, and the triangular rhythm of the façade reads like a compositional refuge from the restless right side. Even here, however, the crowd’s posture is not purely devotional. Some faces turn away; some argue; some seem to use the steps for vantage rather than prayer. Faith persists, but it competes with spectacle and fatigue. The painting neither praises nor condemns. It simply records the uneasy truce among impulses that modern life requires.

Allegory of Modern Civilization

Taken as a whole, the picture proposes a compact allegory. At the bottom is the sea of the social body—hungry, striving, hopeful, and at risk. To the left stands a memory palace where inherited meanings dwell. To the right rises the factory of means, the realm of production. Over all hangs a canopy of smoke, the price of progress and the veil through which we try to think. Reason is not a solitary genius floating above this scene. It is the practice by which a community allocates attention, organizes labor, and chooses which light to walk toward when visibility is poor.

The Soundtrack: Heat, Hammer, and Chant

Although the image is quiet on paper, it vibrates with sound. The furnace booms and breathes; a hammer pounds; chains clink on a crane. From the church, one imagines chant spilling into the open air, while in the street bodies shout, plead, barter. Mucha has always painted sound through gesture. Here bent backs and lifted arms provide the percussion and melody of a city trying to keep time with its own complexities.

Time of Day and the Tempo of Work

The work reads as evening or late afternoon—the hour when furnaces still roar but workers begin to count the cost, and churches glow as they welcome vesper services. The timing matters. Reason in an exhausted society tends to turn brittle; in a rested one it can be generous. Mucha paints the hour when decisions made from fatigue can slide a community toward damage. The viewer feels the weight of lateness and the invitation to return tomorrow with clearer eyes.

The Viewer’s Position and Moral Choice

Mucha places the viewer on a low platform in the foreground, close enough to feel the press of bodies and the heat of the forge. We cannot remain neutral spectators. To one side is the church’s door; to the other, the factory’s mouth. In front of us, fellow citizens jostle for dignity. The composition becomes an ethical map: where will attention go, where will care be invested, which lights will be tended, which closed, and at what human cost?

Dialogue with “Age of Love”

Seen beside “Age of Love,” this work sharpens its argument. The earlier sheet builds a civic space around a circle of meeting and a gate of welcome; this painting shows what happens when meeting spaces are swallowed by production and when welcome narrows to doorways people must fight to reach. The two images together outline a program for survival: an age of reason worth having must be held inside an age of love, or the fire will consume the city that needs its warmth.

Technique and Medium as Meaning

The study-like surface—thin washes, visible paper, drawing that never entirely recedes—feels intentionally provisional. Mucha could finish with enamel certainty when he wanted; here he leaves edges open. It’s a candor about the peril of the moment: no completed mural can tell us what to do next. The best art, like the best reason, is a framework for action rather than a doctrine that excuses us from it. The sepia also reads like smoke-stained memory, as if the image were recovered from a wall after a fire.

Psychological Reading

The crowd’s faces range from zeal to terror. Some stare with rapture at the furnace, transfixed by the promise of mastery; others stretch toward the church, craving a larger story; many are turned toward one another, as if realizing that neither altar can replace the neighbor whose hand they hold. The body language is diagnostic: upward reach without neighborliness becomes fanaticism; inward retreat without shared labor becomes paralysis. Mucha’s psychology is social and sober.

Moral Ambiguity as Integrity

The painting refuses propaganda. It neither worships technology nor mocks it; neither enshrines piety nor dismantles it. The integrity lies in the insistence that a decent society must constantly arbitrate among goods that can turn to harms when unbalanced. “Age of Reason” is not an answer. It is a disciplined restatement of the question at a time when too few people were asking it out loud.

Contemporary Relevance

For a viewer living amid new machines, new cults of efficiency, and renewed pressure on institutions of meaning, the painting feels prescient. We still argue about which lights to tend, which doors to keep open, which fires to bank, and how to keep crowds from being reduced to fuel. Mucha’s late vision suggests a heuristic: watch what any power does to bodies at close range; ask whether a practice makes neighbors more visible or more interchangeable; measure progress in breathable air rather than in output alone.

Why the Image Endures

“Age of Reason” endures because it compresses the modern predicament into an image that is both particular and portable. The church and furnace are specifically European and eternally human; the crowd is Prague in 1938 and any city at dusk; the smoke is history and today’s feed of noise. With almost no color and no ornament, Mucha the designer of spectacular posters becomes a witness. He tells us that reason worth the name is a labor—messy, communal, and urgent—and he gives us a picture sturdy enough to carry that truth forward.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Age of Reason” is a nocturne of industrial light and human heat, a study where crowds become sentences and machines become questions. The painting neither scolds nor soothes. It asks us to notice how quickly clarity can become glare, how easily warmth can devour oxygen, how necessary doors of meaning remain when the city burns bright. In 1938, that question was a matter of survival. It still is. The canvas suggests a path: shape an age where the fire serves the circle of neighbors, where the door is not a trap but a welcome, and where reason is the patient craft of holding those goods together.