Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

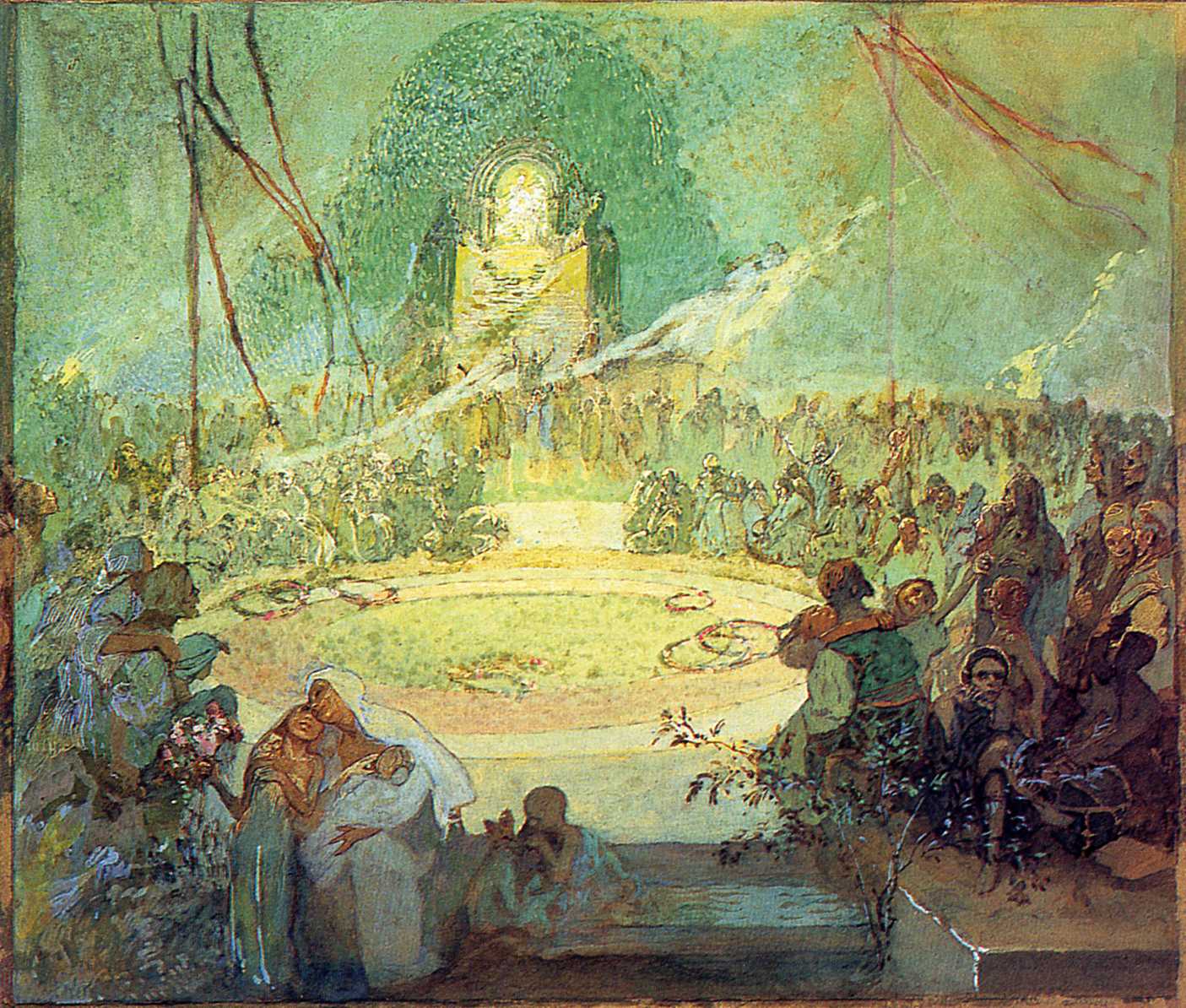

Alphonse Mucha’s “Age of Love” (1938) is a late, visionary sheet that reads like a soft-spoken manifesto. Composed in aqueous greens and pearly lights, the composition opens into a circular clearing ringed by humanity, while a radiant gateway rises at the far end like a blessing made visible. Families lean together in the foreground, children are lifted for a better view, garlands lie on the turf, and long ribbons rise to frame the scene. The effect is celebratory and contemplative at once. Where Mucha’s early fame came from glamorous posters and the monumental sweep of The Slav Epic, here he turns to a watercolor meditation that proposes love as a civic force, not a private sentiment. In the anxious Europe of the late 1930s, this was a daring kind of hope.

Historical Moment And The Vision Behind The Work

By the time he conceived “Age of Love,” Mucha was in his late seventies. He had invested decades in a culture-building project that fused design, national memory, and spiritual imagination. The ink was barely dry on the new Czechoslovak republic when the world slid toward another war. In that context, he sketched a cycle of allegorical “ages,” exploring states of human flourishing as if to name what must be defended. The choice to paint with watercolor and pencil speaks to swiftness and intimacy; this is a studio vision, compact yet capacious, designed to be read at human distance. Rather than telling a single historical story, he builds a metaphorical space in which a people rehearses tenderness as public ritual.

A Circular Clearing As Social Heart

The composition is organized around a broad circle of grass at center, edged by two rings of seated and standing figures. Circles are Mucha’s lifelong grammar—halos, medallions, archways, and wreaths—forms that gather attention and enfold communities. Here the circle is empty of monuments and crowded with persons: not a throne room but a commons. The emptiness is active; its green silence anchors the chatter and motion around it, like a village green prepared for dance. Floral wreaths rest on the turf as if marking the starts of dances or games. The circle becomes the picture’s thesis: love is an arena, not a pedestal, a space made by presence and kept open for meeting.

The Radiant Stair And The Gate Of Welcome

Opposite the viewer, a broad stair climbs toward a luminous arch where a figure in white seems to stand, suffusing the air with light. Two dark pilasters—guardians or caryatids—flank the ascent, lending the gate the dignity of temple and the hospitality of a city festival. A shaft of brightness falls diagonally from that portal into the circle, uniting heaven’s rhetoric with earth’s gathering. Mucha often uses architectural forms as ethical cues. Here the stair does not isolate the elevated from the ordinary; instead, it offers a way up and a way back, suggesting that arrival at the highest good is communal and available.

Families At The Threshold

In the immediate foreground, a compact group forms the work’s emotional anchor. A mother presses her cheek to a young woman’s forehead; an infant is swaddled and held close; another child sits on the ground, absorbed in the scene. This cluster is domestic yet public. Love begins at home, the picture says, but belongs in the square. The gestures are specific enough to feel lived—a hand at the nape, the weight of a bundled child, the slight lean that reveals trust. Mucha’s genius for drapery and posture does the rest, turning ordinary contact into liturgy.

The Crowd As Choir

Moving outward from the foreground, figures arrange themselves in soft masses that read like choirs answering one another. Groups raise arms, clasp hands, or lean shoulder to shoulder. The left-hand side is quieter, with sitting figures and watchers; the right-hand side is more animated, with people craning for a view and passing children along the line. This distribution creates a stereo effect across the picture: murmur to the left, cheer to the right, a shared hum in the middle. Although the medium is watercolor, the sound is palpable.

Ribbons, Garlands, And The Grammar Of Celebration

Tall poles at the sides carry long red streamers that arc into the sky. Garlands lie at intervals within the circle. In Mucha’s vocabulary, ribbons and wreaths are not mere ornament; they are instruments that tie space together. The streamers draw the eye upward and outward, preventing the ring from feeling closed. The wreaths mark stations in a gentle ritual—perhaps dances, perhaps vows. The presence of flowers throughout turns love from a mood into a schedule of acts: decorate, gather, offer, remember.

A Color Climate Of Hope

“Age of Love” breathes a limited but resonant palette. Cool greens dominate the circle and the vault of air, warmed by touches of rose and coral where faces and fabrics catch light. Along the central axis, citrine and ivory push brightness toward the gate, so the eye climbs without hurry. This color climate is not sugary pastoral; it’s springtime after a winter of earnest labor. The greens are mixed with blue; the highlights are gentle; shadows are transparent enough to preserve nuance. The palette’s restraint keeps the allegory believable. Love here is not carnival glare; it is weather people can live inside.

Watercolor And Pencil As Vehicles Of Tenderness

Mucha’s command of lithographic line and tempera glazes is famous, but on this sheet he uses pencil and watercolor to render a different kind of clarity. Pencil establishes contour and anchors the architecture, while thin washes create figural masses without heavy modeling. The medium’s transparency mirrors the theme: love is a form of seeing-through, of allowing light to pass between persons without walls. Edges soften where bodies touch and sharpen where the architecture demands it, a choreography that makes the scene breathe.

The Luminous Gate As Ethical Horizon

The glowing portal at the far end is the painting’s subtlest device. It reads as temple, stage, altar, or simply an opening into fuller life. Its light pours downward like recognition, stretching into the circle like a path. Crucially, the gate does not dictate dogma. Mucha gives no emblem or inscription that would restrict interpretation. The image remains hospitable to multiple traditions while insisting on a shared horizon: communities are healthiest when their festivals point beyond themselves to something worthy of ascent.

Love As Public Practice, Not Private Heat

The title invites misreading if taken narrowly. Nothing here is erotic in the sense of courtship or seduction. Instead, love is civic, intergenerational, and ritual. Couples exist, but they do not dominate; children and elders are co-equal presences. The ring of spectators is not a crowd gathered to watch a spectacle; it is the spectacle, an organism of neighborliness. The composition refuses the straight line of parade or the hierarchy of dais. It offers a circle in which every position is both center and edge depending on who is looking.

Resonances With The Slav Epic

The scene converses with Mucha’s earlier murals. The procession of luminous saints in “The Introduction of the Slavonic Liturgy” is transformed here into human neighbors. The ascending light and communal movement echo “The Apotheosis of the Slavs,” but the tone is less triumphal and more pastoral. The central green recalls the orchards and meadows that hosted learning and printing in other panels, redeployed now as an arena for tenderness. Where the Epic chronicled ordeals and reforms, this sheet distills their harvest: the habit of gathering in gratitude.

The Viewer’s Vantage And The Ethics Of Witness

Mucha positions us just outside the circle, at the lip of the grassy arena, near the cluster of mothers. We are neighbors rather than judges, invited to step forward or simply watch with affection. The vantage avoids spectacle’s distance and coercion; it encourages consent. The painter has always been attentive to how viewers are positioned—street audiences for posters, gallery walkers for murals. Here he builds a seat for the soul inside the scene and asks us to occupy it.

Time Of Day And The Sense Of Season

The light suggests late afternoon or early evening, that hour when community festivals begin. The sky’s upper register darkens toward blue-green, while the ground keeps a filtered glow. A faint, sparkling spray of dots around the gate reads as lanterns, stars, or simply the dust of celebration caught in a beam. Season feels like late spring or early summer, when grass is generous and nights are kind. In a Europe nearing catastrophe, this temporal choice matters. Mucha paints an hour that human beings can love without fear.

The Role Of Children And The Work Of Future

Children are everywhere—on laps, on shoulders, arranged at the edge of the circle where they can watch and be watched. Love’s claim on the future is not sentimental here; it is logistical. Adults make room, lift, support, and explain. The composition ensures that teaching is visible: a child stares at the bright gate; another studies the wreaths; infants sleep as if to bless the gathering by trusting it. The picture becomes a manual of transmission.

Subtle Notes Of Vulnerability

The harmony is not naive. Look closely and you’ll find faces darkened by fatigue, figures whose posture suggests poverty, and patches where foliage thins to dust. Mucha never allows allegory to cancel reality. The crack visible near the bottom edge in some versions of the sheet, whether literal damage or a suggestion of wear, echoes this vulnerability. Love is not escapism; it is a power that must be chosen again amid frayed edges.

Architecture As Memory And Promise

The seated statues flanking the stair, the long poles with streamers, and the vaulted glow above the gate together create a civic architecture that is both old and new. It feels like a site used many times before but ready to host tomorrow’s vows. By refusing to make the architecture specific to a single nation or creed, Mucha keeps the space available to any community committed to kindness. It’s a picture of tradition in the best sense: forms that can survive because they serve persons rather than the other way around.

Movement Without March

One of the painting’s quiet triumphs is its choreography. Everyone appears to be in motion, yet no one marches. Movement is circular, exchanging, improvisational. This is dance rather than parade, conversation rather than edict. In the 1930s, when authoritarian spectacles favored straight lines and hard rhythms, Mucha draws a counter-image: the politics of softness, the ceremony of encounter.

Drapery, Texture, And The Body’s Dignity

Even in watercolor the artist’s love for cloth is evident. Veils fall in translucent layers that catch gate-light; shawls wrap infants with believable weight; tunics ripple as bodies twist to see. Texture becomes a form of courtesy. The figure is never reduced to silhouette alone; it is granted the tactile specifics that say “this person matters.” Cloth in Mucha’s hands is ethics.

The Place Of Nature

Plants fringe the foreground, loose and modest. They are not grand symbols but neighbors. The small shrub near the front has the humility of the everyday, the kind of plant you barely notice until sunlight finds it. Meadows and hills in the distance keep their anonymity. Love needs a place, the painting says, but it does not demand spectacle from nature—only shelter and room to gather.

Technique That Serves Breath

The sheet’s technique is deliberately light. A mesh of pencil gives structure to figures and architecture; wash floats over it like air. In places the paper glows through, becoming the source of light itself. The approach lets the viewer’s imagination complete details, an act that mirrors love’s own habits: to supply what is missing with generosity, to read charitably, to let others grow into focus over time.

Why The Image Feels Urgently Contemporary

The painting’s argument is astonishingly modern. It implies that communities become humane not merely by resisting harm but by practicing love publicly—by designing spaces where people can see each other well, where children are lifted, where elders can sit and still belong. It offers an image of togetherness that is neither uniform nor chaotic, a choreography sturdy enough to hold difference. In an era hungry for images of nonviolent strength, “Age of Love” feels like a blueprint.

Reading The Sheet Beside Mucha’s Final Years

Mucha did not live to see the war that soon arrived. This sheet, steeped in patient light, serves as both wish and warning. Wish, because it imagines a social body gathered around joy. Warning, because it insists that such gatherings must be constructed—by ritual, by architecture, by choice—or fear will fill the vacuum. The artist who once used arabesques to sell theater tickets now offers a gentler persuasion: organize life around tenderness and the gate will open.

The Viewer’s Invitation

Standing before the work, one feels invited to step onto the grass, to pick up a wreath, to take a seat on the ring and keep someone company. The intimation is simple and demanding. Love is not a mood we admire from a distance; it is a place we enter by showing up. The watercolor’s very lightness aids this invitation. Heavy paint would declare; light wash proposes.

Conclusion

“Age of Love” distills Alphonse Mucha’s life-long visual language into a humane vision for the public square. A circle to gather us, a gate to orient us, families to remind us what matters, ribbons and wreaths to teach us how to celebrate, and a color climate that lets breathing feel like prayer—these are the elements of the image and, by implication, of a good society. Painted on the edge of darkness, it refuses despair and refuses bombast. Instead, it offers a practice: make a clearing, bring the children, lift your neighbor’s face into the light, and keep the gate open.