Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

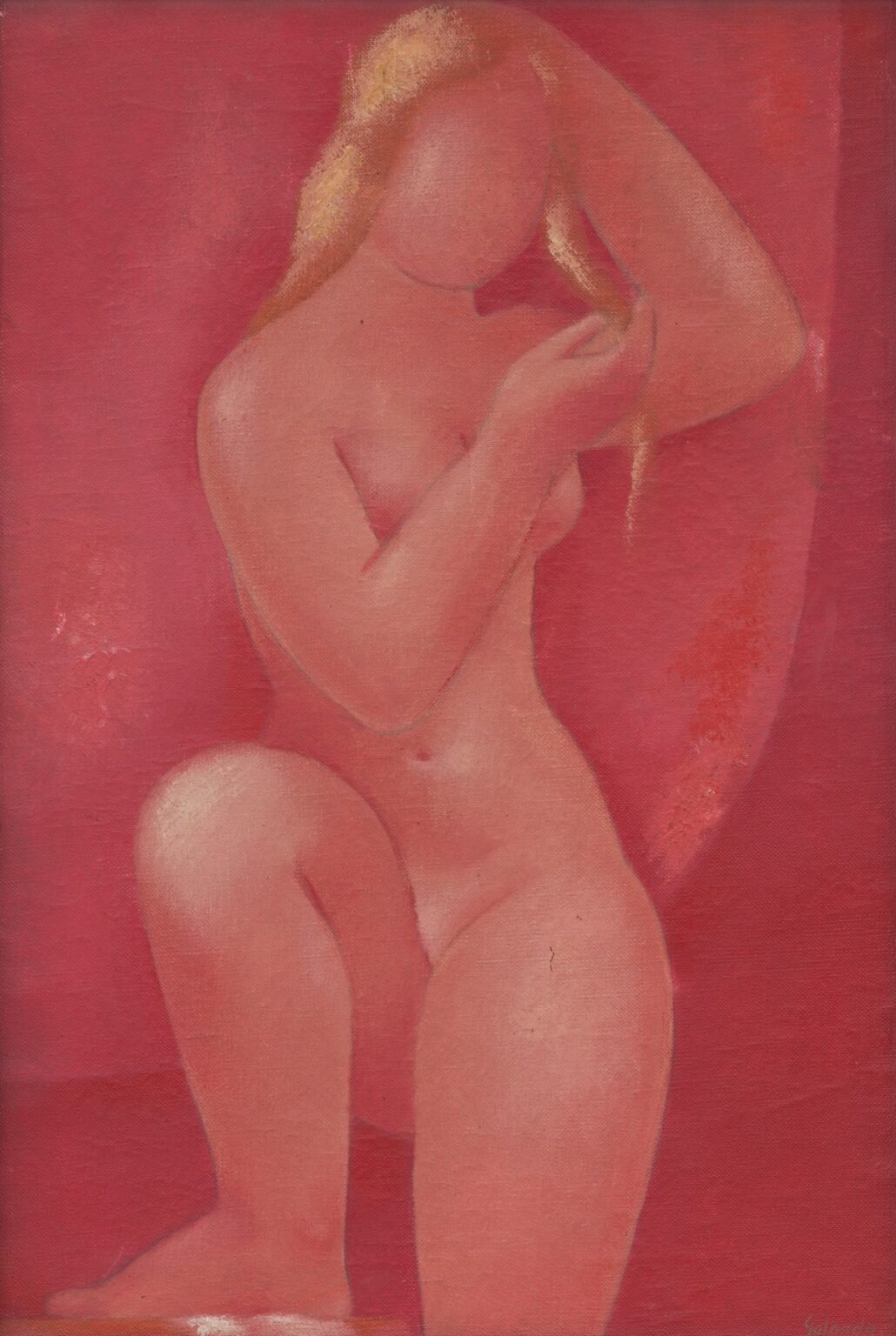

In After the Bath (1932), Slovak artist Mikuláš Galanda presents a modern interpretation of the timeless nude, marrying simplified form with expressive color to capture both the sensual pleasure and the introspective calm that follows immersion in water. Executed during the interwar period, this work reflects Galanda’s exploration of European avant‑garde currents—particularly Cubism and Fauvism—while forging a distinct Central European modernism. The painting’s predominant red and pink tonalities, its gently abstracted figure, and its quiet, almost ritualistic mood invite viewers to consider the intimate relationship between body, color, and space. Through an analysis of its historical context, compositional structure, color palette, thematic resonance, and technical execution, we can appreciate how After the Bath exemplifies Galanda’s innovative synthesis of international modernism and local cultural identity.

Historical Context and Artistic Influences

Created in 1932, After the Bath emerged at a pivotal moment for Slovak art. In the years following World War I and the founding of Czechoslovakia, a generation of young artists sought to assert a national modernism that could stand alongside Parisian and Central European avant‑garde movements. Mikuláš Galanda (1895–1938) was a leading figure in this effort. He studied in Budapest and Prague, where he absorbed influences from Cubism’s fractured planes and Fauvism’s intense hues. By the early 1930s, he had distilled these lessons into a personal style defined by simplified, rhythmic forms and a bold embrace of pure color. After the Bath reflects this evolution: the figure’s curves recall the volumetric explorations of Cézanne, while the painting’s limited palette and flattened space evoke Fauvist colorism and Cubist abstraction.

Composition and Spatial Organization

At first glance, the painting’s composition appears straightforward: a solitary nude woman kneels in profile, combing her long, golden hair. Yet Galanda’s arrangement is carefully balanced. The figure’s vertical silhouette—her raised arm and extended torso—anchors the composition, while her bent leg and the sweep of her hair introduce a counterbalancing diagonal. The background consists of two large, overlapping ovoid zones of red, framing the figure and creating a subtle sense of depth despite the overall flattening of space. These zones also echo the shape of the figure’s head and shoulders, weaving a visual rhythm across the canvas. Negative space recedes behind the figure in a deeper red, lending the impression that she emerges from a glowing, almost stage‑like backdrop. Through this interplay of figure and field, Galanda transforms a simple bathing scene into a lyrical study of form and movement.

The Power of a Limited Palette

One of the most striking features of After the Bath is its near‑monochromatic palette of reds and pinks, contrasted only by the figure’s pale skin and golden hair. This deliberate chromatic choice heightens the painting’s emotional intensity. Red, as a color, carries associations ranging from warmth and vitality to passion and introspection. In Galanda’s hands, it becomes the skin of the painting itself—a sensuous environment that envelops the figure like a blanket of warmth. Subtle modulations in hue and value—soft rose, deep crimson, coral highlights—allow the form to emerge with three‑dimensional solidity despite the overall flatness. The golden hair, rendered in ochre and light yellow, provides a focal contrast that draws the viewer’s gaze to the woman’s head and her intimate act of self‑care. By limiting his palette, Galanda ensures that every tonal shift becomes charged with expressive potential, turning the entire canvas into a unified field of emotion.

Simplification and the Modern Nude

Galanda’s treatment of the nude diverges from academic naturalism, opting instead for a modern synthesis of simplification and suggestion. The woman’s body is captured with smooth, planar surfaces: her arms and legs are reduced to arcuate forms that gently taper and swell, while her torso is rendered as an elegant, elongated oval. Anatomical detail—musculature, bone structure, delicate shading—is bypassed in favor of a more distilled, harmonious shape. This abstraction does not obscure sensuality; rather, it elevates the figure to a universal ideal of beauty. The rounded knee and the subtle curve of the breast speak in the language of archetypal form rather than individual portrait. In After the Bath, Galanda demonstrates that modernist simplification need not diminish the emotional power of the nude—it can, instead, distill it to its purest essence.

The Act of Bathing as Ritual and Reflection

Beyond its formal qualities, After the Bath resonates with thematic depth. Bathing has long held symbolic meaning in art and literature: it is a ritual of cleansing, renewal, and intimate solitude. Galanda’s depiction captures this moment of transition—water has been shed, and the woman now stands poised between immersion and dress, between private vulnerability and public appearance. By showing her combing her hair rather than wrapping herself in a towel or garment, Galanda emphasizes the lingering sensual pleasure of the bath and the contemplative afterglow it brings. Her downward gaze suggests introspection; she is alone within a timeless space, removed from ordinary concerns. In this way, the painting invites viewers to reflect on their own moments of personal transformation and quiet ritual.

Light, Texture, and Surface Treatment

Although the light source in After the Bath is not explicitly defined, Galanda’s handling of form and color suggests a soft, diffuse illumination. Highlights on the figure’s shoulders, arm, and thigh are rendered in slightly lighter reds and pinks, implying the gentle play of light across her skin. The hair, painted with textured strokes of golden yellow and pale ochre, catches more direct emphasis, evoking a subtle shimmer. The background’s flat planes accentuate this modeling effect: without competing detail, the figure’s surfaces appear all the more palpable. Galanda’s brushwork varies from smooth blending on the body to more visible, almost pastel‑like marks in the hair and background edges. This combination of techniques produces a tactile quality: the viewer senses the warmth and softness of skin, the weightlessness of damp hair, and the enveloping warmth of the red space.

Interplay of Figure and Ground

A key innovation in After the Bath is the seamless integration of figure and ground—a hallmark of modernist painting. Rather than position the model against a detailed setting, Galanda immerses her within a field of color that becomes both background and aura. The red zones behind her head and body do not fade away; they resonate with her flesh tones, creating an optical vibration that unites painting and figure. This approach dissolves the boundary between the subject and her surroundings, suggesting that the emotional state of the figure is inseparable from the pictorial space itself. Such unity reflects modernist theories of art as an autonomous, self‑referential system, where color and form generate meaning independently of narrative context.

Cultural Resonances and Slovak Modernism

While After the Bath embodies international modernist trends, it also resonates with specific regional concerns. In the 1930s, Slovakia was forging its cultural identity within the new Czechoslovak Republic. Artists like Galanda sought to articulate a modern expression that spoke to Slovak sensibilities—an embrace of folk traditions, natural landscapes, and national mythologies—while also engaging with European avant‑garde. Although this painting does not depict folk motifs directly, its emphasis on simplicity, directness, and emotional authenticity reflects a broader search for art that could transcend provincial boundaries and resonate with universal human experiences. In this light, After the Bath stands as both a personal vision and a milestone of Slovak modernism.

Comparative Perspective: Galanda and His Peers

Comparing Galanda’s After the Bath with contemporaneous works by European modernists reveals both affinities and distinctions. Like Pierre Bonnard’s bathing scenes, Galanda’s painting captures intimate domestic rituals in rich color. However, where Bonnard often uses decorative pattern and loose brushwork, Galanda opts for clearer form and more assertive planar construction, aligning him more closely with the sculptural qualities of Amedeo Modigliani or the color fields of Henri Matisse. Yet unlike either, Galanda’s red‑dominated palette and the abstracted figure carry a uniquely Central European sensibility: a blend of austere restraint and warm expressivity that marks his work as distinct within the interwar avant‑garde.

Emotional Impact and Viewer Experience

After the Bath engages viewers on both sensory and emotional levels. The painting’s evocative redness may at first feel disorienting—an immersive environment that demands close attention. As the eye adjusts, the figure emerges in luminous relief, and the tactile quality of her skin and hair evokes visceral empathy. One senses the quiet pleasure of a clean, renewed body and the inward focus of a private moment. Yet there is also an undercurrent of tension: the abstract space offers no escape, no hint of setting beyond the enveloping red. This ambiguous environment transforms the scene into a universal symbol of the human condition—moments of solitude and self‑care experienced within the confines of one’s mind and emotions. Viewers find themselves drawn into an internal dialogue about vulnerability, renewal, and the interplay of exterior and interior life.

Technical Mastery and Artistic Legacy

Galanda’s technical command in After the Bath is evident in his precise draftsmanship and his nuanced modulation of color and tone. The painting’s surface—whether in oil or mixed media—appears velvety and unified, yet close inspection reveals the careful layering of pigments and the subtle transitions between hues. His ability to achieve sculptural solidity with minimal detail speaks to a mature modernist sensibility, one that balances reduction and sensuality. Though his career was cut short by illness in 1938, Galanda’s influence persisted in Czechoslovak art, inspiring subsequent generations to embrace modernist innovation while affirming local cultural roots. After the Bath stands as a testament to his vision—a work that continues to captivate with its bold color, elegant form, and enduring humanity.

Conclusion

In After the Bath (1932), Mikuláš Galanda synthesizes the legacy of European avant‑garde art with a distinctly Slovak modernism, offering a painting that is at once formally rigorous and deeply expressive. Through his streamlined composition, emotive red palette, and subtle interplay of figure and ground, he transforms a simple act of post‑bathing grooming into a poetic meditation on solitude, sensuality, and the self’s renewal. The work’s historical significance lies in its place at the confluence of interwar cultural currents—asserting both the universal power of modernist abstraction and the emerging identity of Slovak art. Today, After the Bath resonates with contemporary viewers as a timeless celebration of the private rituals that sustain the human spirit and an exemplar of color’s transformative potential in painting.